Football: Billy Ray Barnes remembers Bednarik

Published 8:30 pm Sunday, March 29, 2015

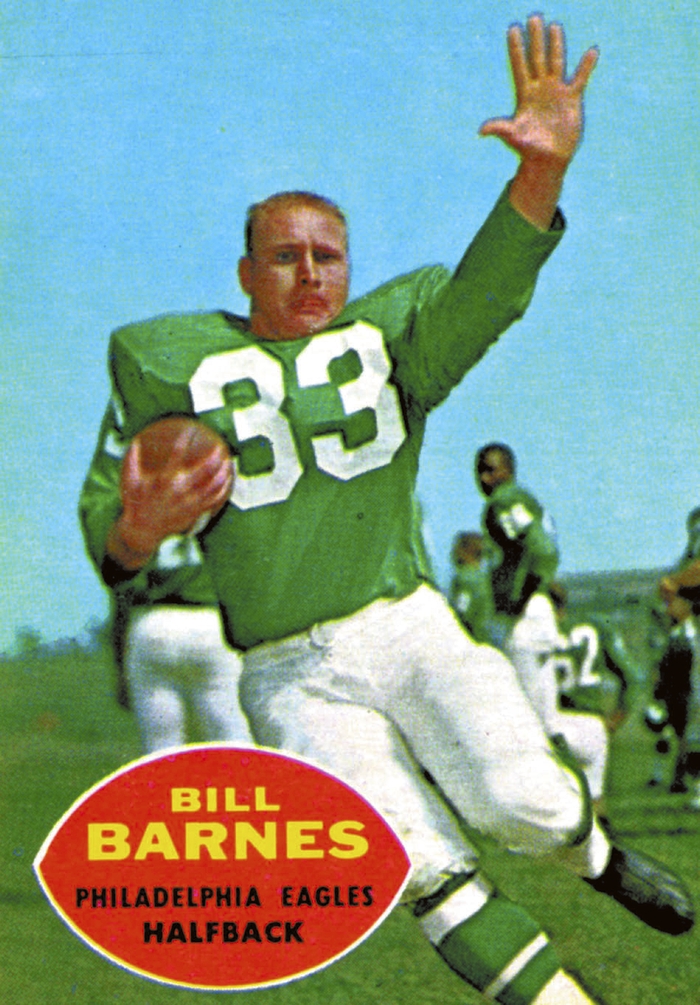

- Landis' Billy Ray Barnes

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

LANDIS — Billy Ray Barnes was involved in a family conversation when he saw familiar images from his football playing days flashing across the bottom of his television screen.

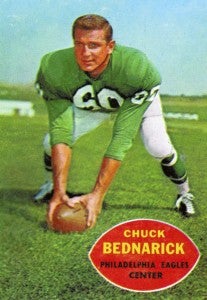

He saw Frank Gifford catch a pass, and then he saw Chuck Bednarik level Gifford as he tried to get to the sideline. Barnes knew instinctively that his longtime friend and Philadelphia Eagles teammate Bednarik had passed away.

Bednarik died March 21. Funeral services in Pennsylvania were held Thursday. He was buried in his Hall of Fame blazer.

The TV footage Barnes saw was from Nov. 20, 1960. The place was Yankee Stadium, and Bednarik knocked New York Giants star Gifford out cold and forced a fumble with a paralyzing blow to Gifford’s chest.

Barnes, a halfback, was on the sideline when that devastating but legal hit occurred. Mostly he remembers the strange sound of that punishing tackle — like a shotgun going off.

“That lick was something else,” Barnes said. “Gifford missed the rest of that season and the next one. The pictures show Bednarik celebrating, but he wasn’t celebrating Gifford being hurt. He was celebrating us recovering the fumble.”

Five weeks after Bednarik’s hit on Gifford, the Eagles beat the Green Bay Packers on the day after Christmas at Philadelphia’s Franklin Field in the NFL championship game

That title game, in a season before Super Bowls, is notable 55 years later for two reasons — it was the only playoff loss of Green Bay coach Vince Lombardi’s career, and it was the last time the Eagles were NFL champions.

“Green Bay was cold, and for years they weren’t good and it was the place they threatened to trade you to if you messed up,” Barnes said. “But then they got Lombardi.”

The 1960 season was far from Barnes’ best year — he was a Pro Bowler from 1957-59 — but he contributed 315 rushing yards, 132 receiving yards and six touchdowns to the championship effort. Bednarik played both ways as a 35-year-old center and linebacker. In the title game, Bednarik was on the field 135 of 138 plays, and he made the bear-hugging tackle on Green Bay fullback Jim Taylor on the final snap to preserve a 17-13 victory.

Little wonder Bednarik is considered the greatest player ever to wear an Eagles uniform.

The events of the 1960 season bound the Eagles tightly together for the rest of their lives. Barnes is a Wake Forest legend and came back to North Carolina after he retired, but he stayed in touch with old teammates through reunions and Hall of Fame inductions. The 1960 Eagles entered the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame as a unit in 2006.

Barnes reunited with Bednarik several times, including five years ago when the 1960 Eagles were honored in Philadelphia on the 50th anniversary of their title.

“Chuck would’ve turned 90 in May, and my 80th is coming up in May,” Barnes said. “I hate to see him go, but he had one heck of a life. I couldn’t go to the funeral. I spoke to the guys (teammates such as Tommy McDonald, Pete Retzlaff and Maxie Baughan attended the funeral) and sent my regards.”

Bednarik, the son of Eastern European immigrants, spoke his first words of English at age 6. At 18, he was a gunner on World War II bombing missions over Germany.

“Our quarterback on the 1960 team (Norm Van Brocklin) was in World War II also,” Barnes said, “He and Chuck saw things there that were a lot of tougher than anything they ever saw on a football field.”

Bednarik went to Penn after the war and became an All-American. Then was a huge part of the Eagles’ 1949 NFL title team when he was a rookie.

After a long series of Pro Bowl seasons, he was going to retire in 1959, but his wife was pregnant with their fifth child. So he went back to work with the Eagles. Their championship season wouldn’t have happened without him.

NFL players didn’t make a lot of money in those days. Most had offseason jobs. Bednarik sold concrete to make ends meet. That explained his fitting nickname — “Concrete Charlie.”

“We didn’t play for the money — we played to win a championship,” Barnes said. “I’d do it all over again.”

Bednarik was a large linebacker for that era at 6-foot-3, 235 pounds, he had a voice like a lion, and there are tales that he punched out a teammate who objected to performing jumping jacks at practice. Former Cleveland Browns great Jim Brown, the best of the best, told ESPN that Bednarik was the most physical guy he ever played against.

Barnes said Bednarik’s athletic skills extended to golf, even with fingers mashed and gnarled like old tree limbs and his right pinky extended almost at a right angle from his hand after years of battling in NFL trenches.

“He won lots of long-driving contests,” Barnes said. “He had this amazing reach, arms down to his knees. He was a really good athlete.”

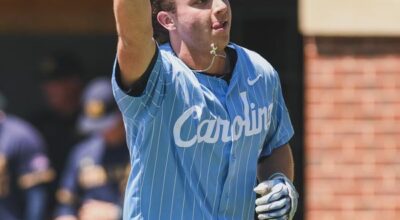

So was Barnes, a 1,000-point basketball scorer at Landis High, the ACC’s first 1,000-yard running back at Wake Forest, and the third baseman for Wake Forest’s 1955 national championship baseball team.

Barnes has been part of two unique team feats. Not only have the Eagles not won the NFL championship since 1960, no ACC team has won the College World Series since Wake Forest triumphed in Omaha, 60 seasons ago. Barnes fielded the ground ball that ended the championship game.

Wake Forest is celebrating the 60th anniversary of that national championship on May 9 when the Deacons play N.C. State. Barnes and two Salisbury natives, Frank McRae and Bob Waggoner, were starters. Barnes batted .319 that year and led the ACC in stolen bases with 17.

Waggoner scored the only run in a 1-0 College World Series win against Colgate. McRae went 5-for-5 in the championship game, a 7-6 victory against Western Michigan.

Barnes is in the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame, but he’d like to see that 1955 Wake Forest club enshrined as a team.

“People always think that 1960 NFL championship was my biggest thrill in sports, but no way,” Barnes said. “The biggest thrill was winning the College World Series when I was 20. We were the first college team from North Carolina to win a national championship.”