Books: Tibbetts writes about a true hero

Published 12:36 am Monday, June 20, 2016

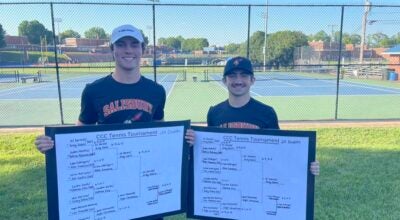

- Former sportscaster Terry Tibbets talks about his book, ‘A Spartan Game: The Life and Loss of Don Holleder.’ The book signing was part of the National Sports Media Association book festival. Photo by Wayne Hinshaw, for the Salisbury Post

SALISBURY — Don Holleder has been part of my memorabilia collection for decades.

His smiling, confident face crowned by a gold football helmet with a black stripe dominates the Nov. 28, 1955 issue of Sports Illustrated.

SI was only a little more than a year old then, but that publication is not worth a lot. You can buy it for under $10 on Ebay. I think it should be priceless.

That Holleder played quarterback for Army at a time when players competed on both sides of the ball, and the Army-Navy game was at least as big as Auburn-Alabama or Michigan-Ohio State is now, was the only thing I knew about Holleder until this weekend when author Terry Tibbetts came to town.

Tibbetts was at the Literary Bookpost on Sunday, signing books and talking to readers, as part of the National Sports Media Association festivities.

Tibbetts, who began his career as a sportscaster before switching to public relations, and then to writing, is the fellow who penned the first biography of Holleder — “A Spartan Game: The Life and Loss of Don Holleder.” It was published in 2011.

Holleder died in 1967, so it was years before Tibbets was compelled to bring his story to light.

“I was 13 when that 1955 Army-Navy game was played and I never forgot it and I remember vividly reading about it when Holleder was killed,” Tibbetts said. “It was always in the back of my mind to write something, and then I finally had the time.”

Holleder was a standout high school athlete in three sports, the All-American boy. Part of his choosing to go to Army was the recruiting effort of Army assistant coach Vince Lombardi. Holleder proved as good as his hype and was an All-America end in 1954. He was 6-foot-2, 200 pounds of crewcut, square-jawed fury and a fellow regarded as a sure-fire NFL prospect.

But that’s where Tibbetts’ story really gets interesting.

Army graduated its quarterback from the 1954 team, and head coach Red Blaik saw Holleder as his best choice as his next QB, even though Holleder had never played in the backfield. Holleder had no passing experience, but much of quarterbacking is leading, and Holleder was the best leader he had.

Holleder was asked to make the position switch and was given a night to sleep on it. There was little doubt about what Holleder’s decision would be, even though it would mean abandoning a position where he’d been a star.

“He was the kind of person who was never going to turn down a challenge,” Tibbets said. “He was one of those people who knows what he can do, and he’s going to do it.”

Holleder turned out to be a lousy passer, but he made up for it with courage, toughness, speed and tenacity. He ran the ball a lot and he was a load to bring down. Army had a winning season, although the team slipped some from where it had been in 1954. Both Blaik and Holleder drew considerable fire from the media and even Army supporters.

Army was 5-3 when it went to take on a formidable Navy team at Philadelphia’s Municipal Field in the season’s biggest game. Navy was 6-1-1 and had a brilliant passing QB in George Welsh.

Blaik didn’t sound optimistic when he told his team the night before the game, “That walk tomorrow, before 100,000 people, to congratulate (Navy coach) Eddie Erdelatz will be the longest walk I’ve ever taken in my coaching life.”

There was silence from the Army team until Holleder spoke up: “Colonel, you’re not going to have to make that walk.”

When Tibbets tells that story that happened 61 years ago, his voice deepens, mimicking what Holleder’s must have been like, and his eyes moisten with tears.

Holleder backed up his guaranteed victory, years before Joe Namath did. He had a lot to do with Army’s 14-6 upset victory on defense, recovering a fumble and flattening a Navy receiver who dropped a fourth-down pass. Army trailed 6-0 but rallied. On offense, Army kept it simple. Holleder threw only twice — one incompletion and one interception — but he inspired his team.

“Army pounded away, same play over and over to the same side of the line,” Tibbetts said. “They overpowered Navy.”

There would be more sacrifices for Holleder. He played for the collegians in their All-Star Game against the Cleveland Browns in the summer of 1956, but he had no interest in pro football. He was a soldier.

He rose to the rank of major, serving in Hawaii and Korea and at West Point as an assistant football coach.

He was a long way from Southeast Asia, but as the Vietnam War escalated that’s where he wanted to be — with his teammates.

He got his wish — with the 1st Infantry Division.

It was October 1967, when Holleder was killed in the battle of Ong Thanh, 40 miles northwest of Saigon.

There were tragic miscalculations and bad fortune that led to his death.

“The Army was looking for the enemy, and they located them,” Tibbetts said. “They sent in 100 or so men, and they were expecting to be opposing 300 North Vietnamese. But there turned out to be 1,400. The Vietamese were there to gather rice, but once the American soldiers crossed a certain line, they were ready to fight.”

Lieutenant Colonel Terry Allen, the American commanding officer, was killed. One rifle company was virtually wiped out. Another sustained heavy casualties.

Holleder, a major, was in the air in a helicopter and arrived for the final stages of the battle. He saw wounded soldiers everywhere. He got permission to have the pilot land, grabbed a pistol, jumped out of the helicopter and headed to help the wounded.

The Vietnamese were withdrawing, but a lingering sniper cut down Holleder, who was sprinting toward the jungle. He was 33 when he died and the father of four young daughters.

“I’m sure his thinking was that it was his duty, his job to try to help his teammates, and there was no one who could,” Tibbetts said. “He ran to the sound of the guns when no one else did.”

Tibbets has made painstaking research into the life and death of Holleder, talking to teammates, to soldiers who served with him, and to his family. One of Holleder’s daughters gave him the full run of an entire room filled with momentos and press clippings.

Initially, the military called the disaster at Ong Thanh — 58 Americans were killed and 60 were wounded out of 147 — a victory, but the press eventually discovered the truth, and things blew up.

Tibbets says it was a turning point, a day that turned many media members against the war. In turn, the media had a lot to do with the faltering of support for the war from the American people.

“History changes quickly, on the flip of a dime,” Tibbets said.

Reverence for Holleder, who was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, has only grown over the years.

Army’s indoor academy’s athletic center bears his name, and he’s in the College Football Hall of Fame.

Army gives a “Black Lion” Award each year to the player who displays the courage, the spirit and the team-above-self character of Holleder.

Most important to Tibbetts, Holleder’s medal have been upgraded over the years.

On April 27, 2012, the Army awarded Holleder the Distinguished Service Cross at a graveside ceremony at Arlington.