Veteran J.L. Horton: ‘I just did what I was supposed to do’

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, November 10, 2015

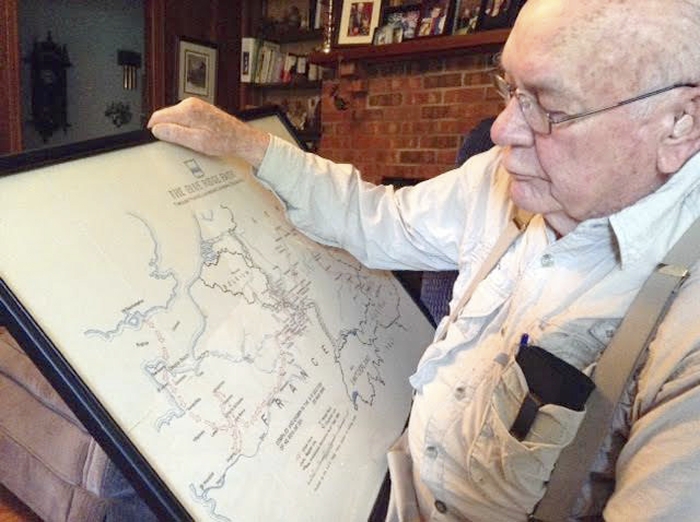

- J.L. Horton looks at a map of the 80th Infantry Division's trek through France, Belgium, Germany and Austria during World War ll. Photo by David Freeze

On a comfortable recliner not far from where he was born, J.L. Horton sat back and told about his life. That story, filled with humor and a little sadness, began when Horton was born into a farming family in 1924, joining two brothers and three sisters. He had finished high school and was working in construction, able to save enough to buy his own nice car. But World War ll came along, and Horton was drafted into the United States Army, entering service in 1943.

First stop for Horton was Camp Croft, S.C., for a few days before his unit was sent to Camp Clayburn in Louisiana for basic training. Four months later, Horton arrived in England, having crossed the Atlantic on the Queen Mary with 17,000 other soldiers.

“It was a smooth crossing on the fastest troop ship available,” Horton said. “We slept in bunks one night and on the deck in sleeping bags the next night. The thing I remember most is the smell of the kidney stew onboard. I don’t know what it was made of, but I did not like the smell.”

Assigned to a general service engineering unit, Horton landed in Scotland before he moved on to spend much of his early time in England building bomb shelters and training for a major invasion.

While sleeping outside in a pup tent, Horton caught double pneumonia and had to stay in the hospital for several weeks. Upon his recovery, he was switched to a different unit.

“The captain told me that I couldn’t go back to my regular unit but would be moved to a combat engineering unit that had lost a lot of men. I begged him but it didn’t work. It was hard to leave my buddies behind.”

Horton was now a member of the 80th Infantry Combat Engineers. Soon, he and his new unit were headed for Omaha Beach, one of the sites of the D-Day Invasion, on landing craft. They landed a few days after the original invasion but still amid German shelling, stepping off into water that was chest deep.

“It didn’t take more than two to three days before I had new friends,” said Horton.

The 80th Infantry Division was involved in heavy fighting as it became the workhorse of General Patton’s Third Army. They fought at Argentan before joining in the Third Army dash across France with battles at St. Mihiel, Chalons and Commercy until stopped by the lack of gasoline and other supplies at the Seille River.

Their next major engagement was at the Battle of the Bulge near Luxembourg and Bastogne, Belgium. On Christmas Day 1944, 80th Infantry soldiers fought across frozen, snow-covered ground against murderous machine gun and mortar fire to free the besieged 101st Airborne Division. Horton remembered the dreadful cold and how he struggled to stay warm.

Crossing the Rhine into Germany and eventually fighting their way to Frankfurt, Horton found a city that had been heavily bombed by the Allies. “Most of the buildings were leveled, but they didn’t get the brewery,” he said.”We found some pink champagne and hid it in the corner of our truck so that the officers wouldn’t see it. That champagne, supposed to be some of the best, lasted through the end of the war.”

Another area of heavy fighting was near the Autobahn, the high-speed German roadway. The Black Forest of southwestern Germany was near there.

“We killed a deer, but we were not supposed to. We fished with hand grenades after we didn’t have any luck with rig fishing. We knew how long to hold the hand grenade after pulling the pin and before throwing it. The fish just boiled up, some of them being brown trout.”

Along the way, the 80th met a unit of Russian soldiers. “They were a rough, big-bodied people. I didn’t think much of them. We made a big mistake by not letting the Germans whup the Russians first.”

With the Germans on the run, Horton’s unit continued into Austria and happened on the Ebensee Concentration Camp. The gate was locked and a truck was used to push the gate open.

“The prisoners knew we were Americans and crowded the gate area. Not a one of them had any clothes on and the skin was stretched over their bones. Four or five went into convulsions and died right then. They had been literally starved to death and most could hardly walk. Seeing this hurt me more than anything I experienced during the war.”

He continued, “The lot was full of people, with a barracks and a courtyard. We each had two packs of K-Rations on us. Crackers, meat in cans and cigarettes. We started to hand them out and they mobbed us. All we could do was to throw the rations to them. It was like a bunch of hogs.”

The soldiers found a railroad running through the center of the camp. Bodies and bones were stacked beside the rail line. “The railroad was 2-3 miles long. The Germans had gone out the other side as we went in.”

Ebensee was one of the most horrific of the Nazi concentration camps. More than 20,000 prisoners were worked to their deaths. The camp was originally designed as a work camp to build tunnels for construction of V-2 rockets, but those tunnels were used later for tank gear assembly. About 350 prisoners died per day in the last weeks of the camp’s existence.

When the Germans knew that the British and Americans were near, they told the prisoners that they were being sold to the Americans and to go wait in the tunnels. The prisoners remained in their barracks and were relatively safe when the tunnels later exploded.

The 80th infantry Division is widely accepted to have fired the last shot on the western front, being one of the last of General Patton’s units still in action. By V-E Day, the 80th had been in battle for 289 days and had captured 200,000 enemy soldiers. Only six of the original members of Horton’s platoon remained at the end of the war.

Horton remembers the night the war in Europe ended.

“We were bunked down about midnight and heard the awfullest racket. The captain and the other officers came around carrying buckets of Schnapps. Nobody slept anymore.”

A point system was used to establish priority of which soldiers could return home. Horton said, “I didn’t have a wife or children, which counted a lot, but I did have lots of months in combat. Some of the guys were sitting around singing in a tent. One had a guitar. An officer came in and wanted to know who Horton was. They told me to get in my dress uniform and where I needed to go. I was awarded a second Bronze Star, making enough for me to get out.”

Horton had been concerned that he may be sent to Japan and the war in the Pacific. His final rank was corporal.

Horton returned to the U.S. on a Liberty ship, much smaller than the Queen Mary. It took two weeks to cross the ocean, part of it through a bad storm.

“I had been away for three years, never having a furlough home. We got back to Fort Bragg, and were told we would have to wait before being discharged. I saw some buses loading and went out and broke in line to catch a bus to Charlotte. If I could have found those ladies later that I cut in front of, I would have apologized,” said Horton.

“From Charlotte, I caught a taxi to Mt. Ulla School where the family was watching my brother Jim play basketball. I walked in and saw my dad, brother and sister. Jim just walked off the court when he saw me.”

With that, Jesse Lee Horton Jr. was home.

Horton had met Hilda Gentry before the war when he was a patient with appendicitis at Lowrance Hospital in Mooresville. She was in her first year of training and was asked to shave Horton. He said, “She must have used the dullest razor. I was cut all over.”

Hilda had been serving as a nurse in North Africa when the war ended but was not discharged until six months later. They were married in 1946.

Horton returned to the construction industry, where he spent more than 30 years. He owned a building supply firm during most of the family’s time in Tennessee and after returning to North Carolina.

The Horton family includes sons Ron and Don and daughter Pat. After retiring, Horton joined his wife for extensive travel all over the U.S. and parts of Europe. They particularly enjoyed traveling on tour buses. Hilda Gentry Horton passed away 10 years ago this month.

J.L. Horton will be 92 in January. “I have been rather fortunate in life,” he said. “And in the war, I just did what I was supposed to do.”