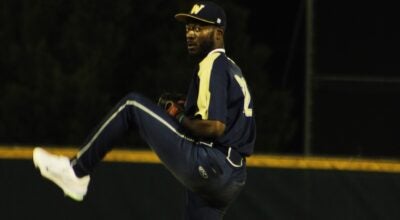

Pro Baseball: Former A.L. Brown star Maher to umpire in Florida

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, June 15, 2011

By Mike London

mlondon@salisburypost

KANNAPOLIS — Winston-Salem Dash second baseman Daniel Wagner stepped into the batter’s box for a preseason game against the Charlotte Knights and heard the last thing he ever expected from a plate umpire.

“Raiders suck!” the ump chirped.

Wagner, the former South Rowan star, noticed a grin behind the ump’s facemask.

“Who are you?” said Wagner.

“Drew Maher, A.L. Brown,” said the umpire, introducing himself as a graduate of a neighbor South isn’t overly fond of.

“Heard of you,” Wagner replied.

Maher and Wagner got back to business after that exchange, but given the nature of the Wonders-Raiders rivalry, Wagner probably figured it might be a good idea to swing at pitches that were anywhere close.

Maher remembers their brief conversation as the lightest moment in his very serious effort to make a career of umpiring.

Maher, 26, has the judgment and the mechanics to wear the blue at a high level. He also has the temperament to get along with people while still taking charge.

Maher was ranked among the best students at the Harry Wendelstedt Umpire School conducted in Ormond Beach, Fla., from Jan. 2 to Feb. 5. He’ll make his pro debut next week in the Gulf Coast League in Florida. Maher will have a Japanese umpire as a roommate.

Maher is remembered locally for the heartbreak of his senior football season. A quarterback who threw for 22 TDs and 1,921 yards as a junior in 2001, Maher’s senior year was over in a matter of minutes when he had a leg shattered at North Rowan in the Wonders’ opening game.

Maher rehabbed from that terrible injury to take some snaps at Lenoir-Rhyne, and he was always a good high school pitcher and first baseman.

Maher graduated from L-R with a degree in sports management and works jobs as a headwaiter and sales consultant in the Lake Norman area.

His third vocation — umpiring — has recently climbed from part-time fun to his passion in life.

“When I was 17, they handed me a rulebook, and I started umpiring on the same Dixie Youth Baseball fields in Kannapolis where I played when I was a kid,” Maher said. “I really enjoyed it and could see it was a way to stay involved in sports. From Dixie Youth, I moved on to middle school and jayvees. After that, it was high school and college games (mostly Davidson and Charlotte) in the area.”

Veteran umpires advised Maher he had the right stuff to make calls professionally. That prompted him to enroll in the high-intensity, five-week Wendelstedt School, which cost him about $3,500.

The Wendelstedt School and the Jim Evans Academy in Kissimmee, Fla., are springboards to umpiring pro games. Both schools tutor about 150 prospects each year.

There were more umpiring apprentices than usual in January because of the economy. Maher learned alongside unemployed lawyers as well as pizza-delivery guys.

Part of the process was rulebook drills in the classroom, with the rest of his instruction on the field through simulated games and some live college games. Maher learned the finer points of the two-man crew (that’s the crew size for leagues below Double A) from instructors who were qualified — MLB umpires.

Teaching started with basics — like always whipping your mask off with your left hand because you’ll need your right to make a call.

“There were 170 in our class when we started and 158 finished the course,” Maher said. “It was guys from California to Wisconsin, and guys in their 20s to their 40s. I had a little jump-start because I’ve been on ballfields since I could walk, but most of the guys had playing experience.”

The best 23 from each of the two schools advanced to an extra week of evaluation by the Professional Baseball Umpire Corp, which pared that top 46 down to an elite 25. Those 25 received minor league assignments. Maher was one of them.

Maher understands the path he’s chosen. The process is long, demanding and not overly lucrative.

As a first-year ump in rookie ball, he’ll drive his own vehicle, buy his own gear and uniforms and make $1,800 a month for calling six steamy games a week for 10 weeks in the rookie-level Gulf Coast League.

The first minute of the first day of umpire school, students are told to hit the road if they don’t have a passion for the game or if they signed up for the money.

Instructors don’t mince words about the long odds of seeing “The Show.” Chances are that just one of the umpires in Maher’s class will make the majors. The professional umpiring club is exclusive — 225 in the minors and a select 68 in the big leagues.

It’s easier to make the majors as a player than an umpire, but Maher is hooked on giving it a shot.

“It’s a different feeling than when I walked on the field as a player, but the butterflies are the same and the excitement is the same,” Maher said. “The big difference is you have to concentate more. It’s a three-hour mental grind. You can’t take a play off. You might be the best umpire in the world for eight innings, but miss a call in the ninth and that’s the one people will remember.”

The timetable is tight. Every pro umpire must begin his career in the short-season leagues, and levels can’t be skipped. After rookie ball, umps work at A, high A, Double A and Triple A on the road to the majors. Umps either move up at least one level every three years or they’re moved out to make room for the next wave of dreamers.

Once umpires make it to Triple A, they have a shelf life of 3 to 5 years to make the final step. They are scrutinized by MLB evaluators and could get a callup if a position opens in the big leagues, but retirements are few and far between. Some Triple A umps also will make it to “The Show” as temps — due to illness, injury or vacations.

Maher thought he knew umpiring before he headed to Florida, but he learned a lot more about making forceful calls. He hopes that knowledge will keep him moving up.

“Timing is critical on a call,” Maher said. “See the play, but then let the crowd make up their mind — safe or out. Then you let them know if they were right or not.”

Maher said that while mastering the rulebook and making the ball-or-strike, out-or-safe and fair-or-foul decisions with a high degree of accuracy is vital, calls aren’t the most critical thing.

“Handling situations is what separates the good ump from the average one,” he said. “That night will come when I’ll have to throw someone out. I’ll have to keep my composure and do it.”

If Maher reaches Triple A six or seven years from now, he’ll earn about $3,200 a month and travel first class.

If he’s that rare big-league ump, he’ll earn about $87,000 as a rookie and his salary could swell to the $400,000 range if his career is long.

Sounds like a tough life, but Maher loves being back on the field enough to try.

“It’s a tough craft and a long process,” Maher said. “But if I can walk out on a big- league ballfield for even one day, it’ll all be worthwhile.”