Banks: Key figure in Duke basketball history visits Salisbury

Published 12:02 am Sunday, May 1, 2022

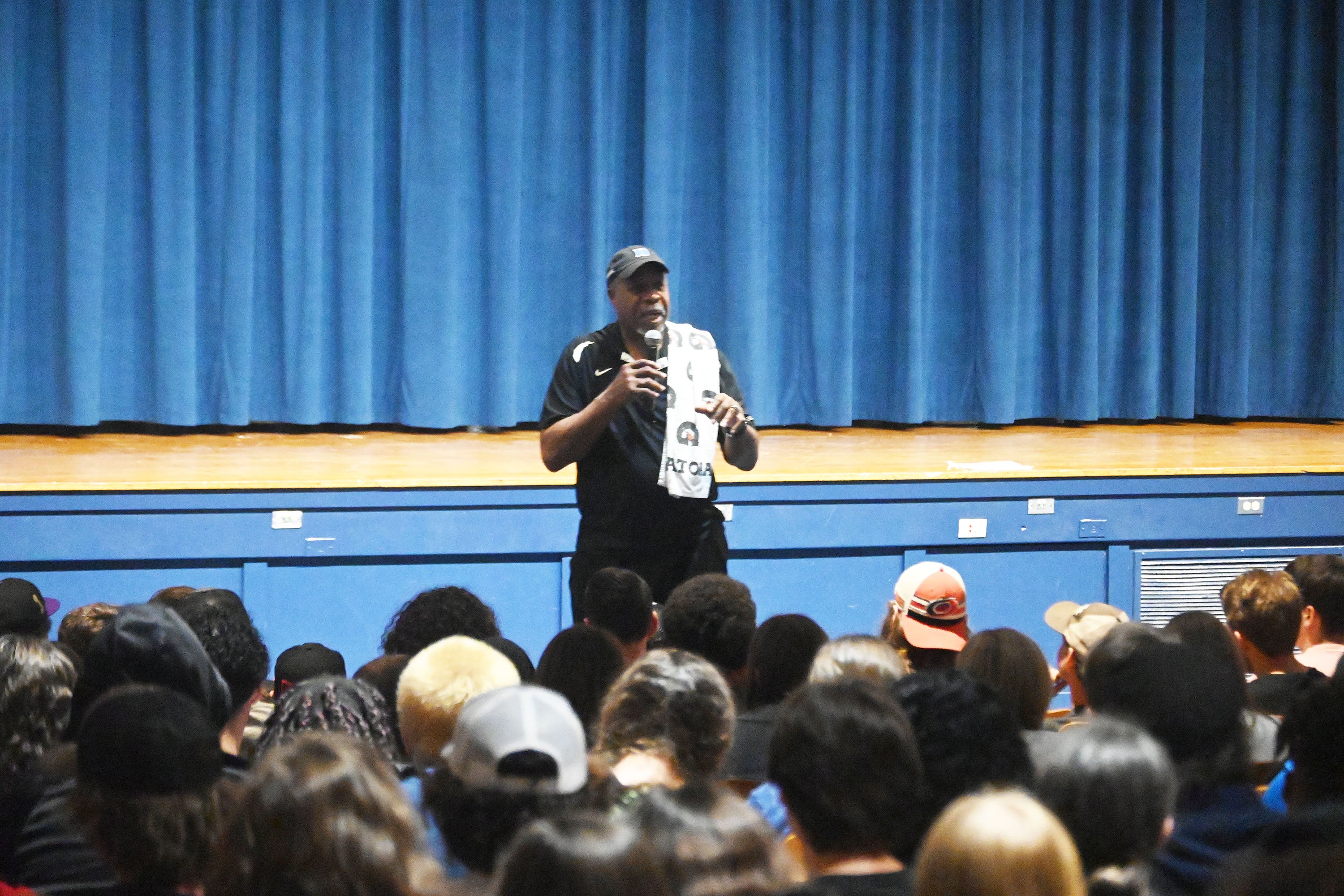

- Madeline Wagoner/Salisbury Post — Gene Banks speaks to East Rowan ninth and 10th graders about the importance of love and respect.

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — Gene Banks still can’t do anything quietly.

When the former Duke basketball star arrived at The Smoke Pit restaurant, patrons could hear him coming while he was still in the parking lot.

Banks was in Salisbury as part of the ABC Upward! program, speaking to high school students in Rowan and Cabarrus counties with a make-good-decisions message.

The exuberant Banks will turn 63 in May. Burliness has replaced the sculpted muscles he once possessed, but he’s still easily recognizable.

Banks hugged old adversaries Ralph Sampson (Virginia) and Al Wood (UNC) and grinned for photos with Rowan County’s No. 1 Duke fan — Memories 1280’s Buddy Poole — who wore his best royal blue shirt.

Banks was not the greatest player in Duke history, but even sharing shots and buckets with fellow 2,000-point scorers Mike Gminski and Jim Spanarkel, he was certainly among the best.

Some Duke historians believe Banks was the most important recruit in the history of the basketball program, and you can make a good case for that.

Banks was one of the most coveted high school players ever. He played for the West Philadelphia Speedboys, a legendary crew that won state titles and drew crowds of such magnitude that they began playing their games as preliminaries to the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers.

Banks was the second of eight children and had lived in 10 different homes by the time he was a senior at West Philadelphia. But he was widely considered as one of the top two high school players in the country, along with New York City phenom Albert King. Most analysts ranked the kid from the Midwest — Earvin Johnson — third in the class of 1977.

Duke was struggling to survive in the ACC in those days, but the Blue Devils became surprise entrants in the Banks recruiting sweepstakes. Banks’ English teacher had asked him to consider Duke for academic reasons. Banks’ high school coach — Joey Goldberg — had worked camps with Duke head coach Bill Foster and liked him and trusted him.

“I didn’t know a lot about Duke except that they were finishing last in the ACC every year,” Banks said. “But I hit it off right away with Bill Foster and I believed I was that guy who could turn things around and make Duke a winner.”

Banks told tales of Dean Smith and his assistants sitting in the kitchen in Banks’ home. Banks does a good Smith impression. He’s got the voice down pat.

Banks also told recruiting stories about Norm Sloan, who was N.C. State’s coach. Banks’ mother loved Sloan. Banks offered a tale of Sloan falling asleep on the couch after consuming a huge meal his mom cooked.

It came down to UNC, Duke, Notre Dame, Penn, which was practically next door for Banks, and UCLA. Wilt Chamberlain, who had been a schoolboy star in Philadelphia, put in a call on behalf of UCLA, pleading with Banks to become a Bruin.

ACC basketball had been integrated by Maryland in the 1965-66 season.

UNC had the league’s first Black superstar in Charlie Scott, who made his varsity debut in the 1967-68 season.

Duke’s first Black basketball player was walk-on Claudius “CB” Claiborne, who was attending Duke on an academic scholarship, in the 1966-67 season.

Ten years after Claiborne, Duke was still woefully behind as far as attracting elite Black basketball players.

The marquee Black recruits Duke had landed — Don Blackman and Edgar Burch — hadn’t stayed long. Willie Hodge, a 6-foot-9 Texan who was the first Black player to stay four years at Duke was solid, but by 1977, a season when all five players on the All-ACC first team were Black, Duke still had never had an All-ACC Black player.

Duke’s 1976-77 squad had just one Black player in uniform — Harold Morrison. He was an average ACC forward, but Morrison would prove to be instrumental in recruiting Banks. On Banks’ visit to Duke, Morrison introduced Banks to North Carolina Central University and Durham’s diverse community outside of Duke, and that sold Banks on where he wanted to be.

In January 1977, with Duke destined for its fourth straight last-place finish in the ACC, Banks stunned the world by announcing at a press conference that he was committing to the Blue Devils.

Notre Dame coach Digger Phelps kept the pressure on Banks right up to the official signing day in April, but Banks signed his National Letter of Intent and left it in his mailbox. Not trusting the U.S. Mail to transport a signature of that importance and with his legal number of visits to the Banks household used up, Foster personally flew to Philadelphia and grabbed Banks’ envelope out of the mailbox.

That wasn’t legal, either, but that precious signature proved to be a transformative moment for Duke basketball.

While he was listed at 6-foot-7, Banks was probably closer to 6-foot-5. He wasn’t a super shooter, but he was a tremendously skilled basketball player. He could score with power or finesse. He could rebound, he could defend, and he could pass. “Tinker Bell,” they called him, because he flew around the court.

“Gene is Coming” T-shirts were showing up on the Duke campus even before Banks ruled the 1977 Capital Classic All-Star Game (USA all-stars vs. Washington, D.C. all-stars), the nation’s biggest high school showcase at the time. Banks’ USA teammates included Wood, King, Johnson and Jeff Lamp, but he was clearly the man. He scored 22. No one else scored more than 12.

Banks changed things right away. Duke tickets were often still available at game time in 1977, but after Banks made his announcement, fans were happy to join the Iron Dukes Club, so they would have the right to buy basketball season tickets for the 1977-78 season. Duke started selling out Cameron Indoor Stadium.

Duke had the ACC rookies of the year in 1976 (Sparnarkel) and 1977 (Gminski), so Banks, fellow freshman Kenny Dennard and transfer guards Bob Bender and Johnny Harrell joined a team on the rise. Banks would become Duke’s third straight ACC Rookie of the Year.

“Duke Breaks Loose” proclaimed a Sports Illustrated cover that featured Banks. Duke came from nowhere to make the Final Four for the first time since 1966 and finished as national runner-up. The Blue Devils beat Phelps’ Notre Dame squad in the national semifinals. Banks had 22 points and eight rebounds in the 94-88 loss to Kentucky in the national title game.

“No pressure, we were just guys playing together and having fun,” Banks said. “No one cared about stats, just wins.”

The pressure came the next season. With all five starters back, Duke was a favorite for the national championship. Duke was very good but could not live up to the burden of those huge expectations in Sparnarkel’s senior season.

In 1980, Duke won its second ACC tournament during Banks’ years. Banks scored 60 points in the tourney, while defending N.C. State’s Hawkeye Whitney, UNC’s Mike O’Koren and Maryland’s King. It was an epic two-way performance.

Duke made it to the Elite Eight, but lost to Purdue. That was Gminski’s last game, and Foster had announced he was headed to South Carolina to coach the Gamecocks.

A few days after the loss to Purdue, Banks was sitting in his mother’s kitchen in Philadelphia.

“The television is on, and the guy says, ‘Duke has hired a new basketball coach and no one can pronounce his name,'” Banks said. “I didn’t know what to think.”

He thought seriously about turning pro, but his mother talked him to staying at Duke, getting his degree, leading the team as a senior, and helping the new coach get started.

The new coach, of course, was Mike Krzyzewski.

Banks and Dennard, who had relaxing in the Florida Keys, reported back a bit late from spring break to meet with the new coach, who had come from Army.

“It was a little tense, and he was telling us about the need for rules and regulations and how we already had crossed over every line there was,” Banks said. “He had this real serious look on his face for a long time, but then he broke out laughing and that broke the ice. All he was asking us to do was to grow up — to be men and to lead his team. We got along.”

Coach K’s first season coincided with Banks’ farewell tour, and he delivered his finest season. He was the first Blue Devil to lead the ACC in scoring since 1967, and he was first team All-ACC for the first time. He had been second team the prior three seasons.

Banks’ Senior Day was one of the more memorable regular-season games in Duke history. Pregame, he handed out red roses to the student sections, just as he had done in his last high school game in Philly. He made the improbable shot that sent the game with UNC into overtime, and he also made the shot in the OT that provided a 66-65 victory.

Duke was down two with two seconds left in regulation, with the full court to traverse, but completed a pass almost to mid-court and called timeout with one second left.

Coach K called a play for freshman shooter Chip Engelland, but Dennard, who was making the inbounds pass, found Banks instead. Banks nailed a high-arcing 18-footer from the circle that somehow cleared the long arms of UNC defender Sam Perkins. When it was all over, Cameron Crazies carried Banks off the court, and his mother came on the floor to embrace him.

“We didn’t run the play we were supposed to run, but Dennard and I knew what we had to do,” Banks said with a smile.

Duke had only modest success as a team in that 1980-81 season and finished it in the NIT. Banks broke his hand in a win against Alabama.

In his final game in Cameron, he sat on the Duke bench — wearing a tuxedo.

He graduated on time with a history degree and he was a commencement speaker.

He averaged 17 points and 8 rebounds for his Duke career.

There were concerns about his height and his outside shot, so Banks lasted until the 28th pick of the 1981 NBA draft. The San Antonio Spurs took him. That was early in the second round in those days.

There was a night in March 1983 when Banks went 10-for-10 from the field against Golden State.

A month later, he reminded everyone who Gene Banks was when he scored 44 points to lead the Spurs to a win over a powerful L.A. Lakers squad. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar led the Lakers that night with 38.

Banks proved to be a solid pro. He averaged double figures for the Spurs twice and he played with Michael Jordan for two seasons in Jordan’s early days with the Chicago Bulls. Banks averaged 11.3 points and 5.8 rebounds in an NBA career that was cut short by an Achilles injury.

Then he had a tremendous career playing in Israel.

When Banks graduated from Duke, he was second to Gminski all-time in scoring, but now he’s slipped to a tie for eighth.

He posted 37 double-doubles and one triple-double. When he graduated, he was in the top 10 in virtually every stat Duke keeps.

Most important, he gave Duke its groundbreaking first Black star. He led directly to a lot of other high school All-Americans coming to Durham.

Growing up in Washington, D.C., a young Johnny Dawkins watched Banks play for Duke, watched him shine on the court — and graduate. Dawkins would become the first key Black recruit for Coach K.

Banks is in the Duke Hall of Fame and the ACC Hall of Fame, but he’s not bashful when it comes to how much he would like to see his number retired by the Blue Devils.

Duke has retired 13 jerseys, but Banks’ No. 20 isn’t among them.

The criteria for a retired jersey at Duke is graduating and earning honors at the national or international level.

Most of the retired jerseys were worn by national players of the year or national defensive players of the year. Banks didn’t achieve that status, but he was a two-time All-American in addition to a fistful of ACC honors, and his lasting impact on Duke’s program is undeniable.

“The jersey retirement, it’s being discussed,” Banks said. “I would cherish it, not so much for me, but for my children. It would be my legacy.”