Isenberg revitalizing dual language program as fourth year approaches

Published 12:04 am Sunday, April 3, 2022

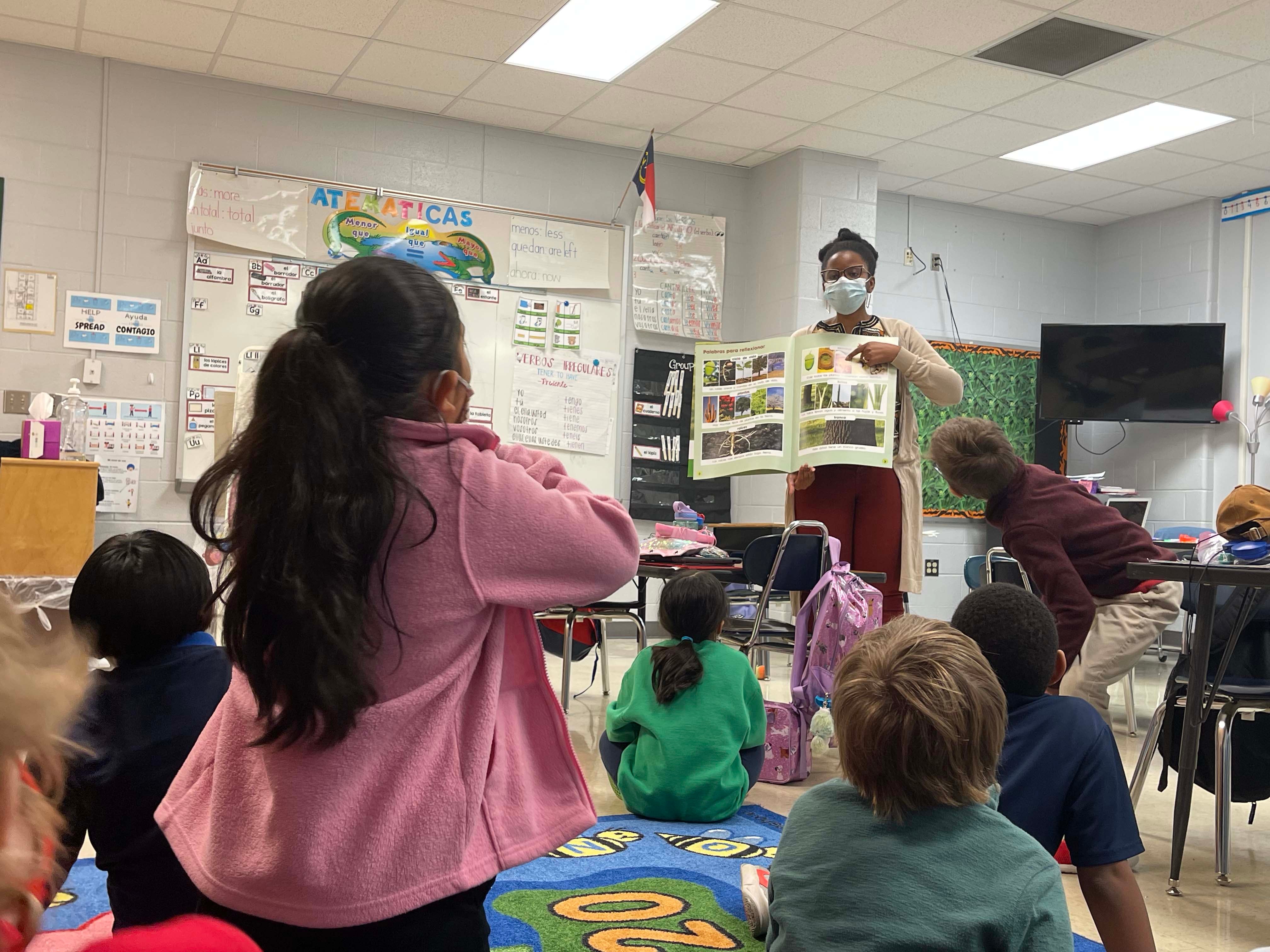

- Submitted photo - First grade dual language immersion students learning about nature in Spanish.

SALISBURY — Isenberg Elementary School approaches language a bit differently than other schools in the county.

Some students go about their days learning primarily in English like the other schools, but other cohorts in a few grade levels get their lessons in English and Spanish.

This is part of the dual language immersion program at Isenberg. Students in the program get all the same lessons as traditional students, but they are split between two languages. The program started in the 2019-2020 school year with its first cohort of kindergarten students.

In 2020-2021, the program added first grade and this school year it added second grade. Everything is lined up to expand to third grade next year and so on until the program includes each grade level.

The program is designed for those who are English speakers first and those who use it as their second language. The immersion in both languages part is key.

“These kids are doing their academic content, rigorous academic content, in Spanish, so they’re not only acquiring the language, but they’re acquiring it in context,” Isenberg Principal Tabitha Miller said.

Miller said the program helps kids get all four modalities of language: reading, writing, listening and speaking.

Miller was hired to take over at Isenberg in November. She said she is, in a sense, the product of an immersion program as well.

The summer after her junior year of high school she went to a state Spanish academy in Virginia. The students in the program only spoke Spanish for a month.

“Spoke, wrote, read, everything we did,” Miller said, adding students were not even allowed to call home and speak in English, though they could write letters for an hour each night.

She went from a basic grasp of the language to fluency and scoring in the highest bracket on the Advanced Placement Spanish exam because of the program.

She had an affinity for languages in school and she wanted to learn Spanish on the same level as her English.

“There’s just something about living that experience,” Miller said. “It’s just different, it makes the world different.”

She started out as a Spanish teacher at the high school level and went on to work with immersion programs. She said she had success improving a dual-language immersion (DLI) program in California and had good results with students learning English as well.

Miller said elementary school is an ideal time to teach a second language, though kids could start even earlier in pre-K. She pointed to the benefits of knowing more than one language like cognitive flexibility, higher self esteem, the advantage in society and cultural awareness.

Isenberg is a Title I school, meaning many of the students are from economically disadvantaged families, and Miller said that means young students are less likely to get the opportunity to travel or have a global experience.

For years, Isenberg has billed itself as a global school and next school year the DLI program will have teachers from the U.S., Colombia, Argentina and Honduras.

Immersion programs are not new. There are more than 200 programs in North Carolina and they have been around for decades.

The COVID-19 pandemic was hard on the Isenberg program’s enrollment. The Post first ran a brief profile about it in the second semester of January 2020 when there was a waiting list, but that initial cohort dwindled to 17 students.

When the pandemic began, students in the first cohort began dropping out of the program, citing difficulty keeping up with the remote learning that became the standard for most of 2020 and 2021.

“It dropped primarily because it was really hard for parents and the fact that immersion is not ideal when it’s online,” Miller said. “In person is really important for immersion.”

But now the program’s enrollment is rebuilding and the cohorts in lower grades are larger. The school is expecting a new kindergarten cohort of about 40 students, the size of the original class, this coming school year and the program is returning to a 50/50 split between English and Spanish in the coming school year.

Some students will join the first grade cohort as well. For dual language programs, Miller said it is generally best practice to limit new entries to the program at first grade.

The program adopted a majority-Spanish approach for its first cohort when they moved to second grade to recoup Spanish progress students had lost. When those students move on to third grade, they will be back to an even split with one teacher providing lessons in both Spanish and English.

The program is also working on its partnership with the firm Participate Learning, which finds teachers from other countries. The company sends coordinators and coaches to work with schools.

Second grade DLI teacher Johana Vargas is originally from Colombia and was recruited by Participate Learning.

She spends most of the day with her class and teaches them only in Spanish. She said the mornings start with some classwork and a meeting. Then there are activities, reading books, weekly vocabulary exercises like using words in sentences and learning about grammar concepts such a prefixes.

As an example, Vargas said last week one of the vocabulary words was extraterrestre, which translates literally to extraterrestrial.

“Many words have a cognate, and they realize that,” Vargas said.

They also work on social studies, math and science in Spanish.

Vargas said her students who are Spanish learners can talk about their needs and observations in Spanish. They can respond to questions about themselves as well.

Vargas said her Spanish learners pay close attention and have to be diligent when they are at school. There are a handful of native Spanish speakers in the class as well.

Vargas said in Colombia many of her lessons were taught to students in English, because it is the expectation for students there to learn a second language.

Heather Nardone has been teaching the English side of lessons in kindergarten since the program began.

“The COVID situation made it crazy,” Nardone said.

When blended learning was happening, her time with students in person each week was limited. But on a positive note, she said parents seem to be more engaged in their children’s learning now and they are excited about the program.

Tynesia Watson received some information about the program when her Jaeson son was preparing to enter kindergarten in its first year. It interested her, so she looked into getting him enrolled. She said it was compelling because the direction of the world and community seems to favor multilingualism.

“There are several jobs now, even that I’ve applied for, where they are leaning more toward those who are bilingual,” Watson said.

Jaeson was also learning a bit of Spanish at his daycare before he started kindergarten.

Watson said the pandemic gave her some doubts and it was a struggle to keep up with the Spanish work at home.

“We were having to do a lot of Google Translate and I just had to keep reiterating to the teacher we are not a Spanish-speaking home,” Watson said.

She said missing the in-person instruction made it difficult to the point she talked to the administration about taking him out of the program, but the family was convinced to stick with it while the school was working on improving its virtual delivery.

“Although my husband and I were ready to pull my baby from the program, he actually enjoyed it,” Watson said.

She said her current concern is that standardized tests in third grade will be given in English though the second grade cohort has been getting mostly lessons in Spanish this year.

Jaeson said he likes learning Spanish words and thinks it is cool he can talk with people a bit in another language.

“I’m good with English and I get a lot of Spanish that way,” Jaeson said.

Math is his favorite subject, and a lot of his work is word problems in Spanish. He said he can understand the problems and solve them.

“It was hard at first when I got to second grade,” Jaeson said.

Sometimes he has trouble understanding lessons in Spanish, but with the help of his teacher he figures it out.