Ray Bost remembered as builder who constructed a larger-than-life legacy

Published 12:00 am Sunday, December 27, 2020

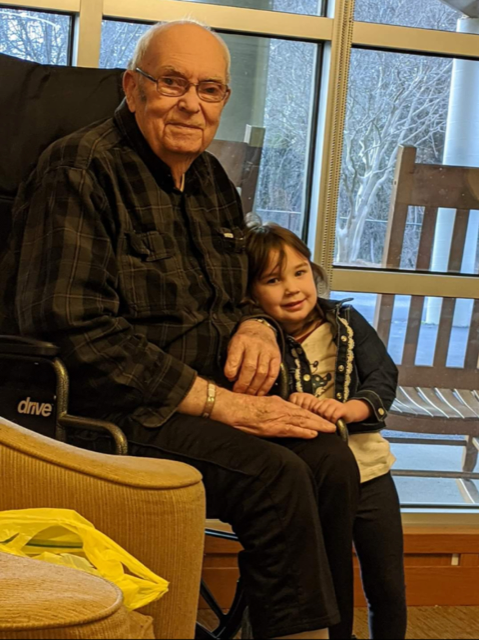

- Ray Bost with his great granddaughter, Morgan.

SALISBURY — Ray Bost lived an eventful life.

A large man standing about 6 feet, 3 inches, he lost an eye to cancer, broke his back, had a knee replacement and accidentally lost a finger with a radial arm saw, among others things. But he also left marks on the county — from houses to church steeples.

He was among the first of the more than 160 deaths in Rowan County attributed to COVID-19, dying April 15 at Novant Health Rowan Medical Center. He was 87. His wife of 69 years, Velma died a year earlier.

Ray contracted COVID-19 while living at The Citadel, a Salisbury nursing home that was previously the site of the largest outbreak in the state. Ray moved into the home in 2017, at that time called Genesis, and Velma moved in the same year so they could be together. Ray and Velma shared a room at the home. The couple’s daughter, Pat, said Ray had some strokes. One took more of his vision and another impacted his ability to walk.

“They even asked to go there,” Pat said.

Early this year, the family did not have much information about COVID-19. Pat said Ray’s physician mentioned the virus during a visit, and a few weeks later the facility entered quarantine in March. There had been other quarantines in the past to protect patients from infections like influenza, but Ray’s daughter never saw her father in person again. The last time she was able to see her father was via a video chat to say goodbye.

Pat said Ray reported feeling stuffy about two and a half weeks before his death, which was not concerning at the time. Ray began to feel weak. He said he did not feel like himself. He was tested for COVID-19 on April 10, but the family received a report before test results were back that he had double pneumonia and it was suspected Ray had contracted the viral infection.

“He got confused and fell out of bed a couple times,” Pat said, adding Ray became so weak the staff had trouble getting him up and he could not answer his phone.

On a Sunday, even though the results were still pending, Pat said the family received a call from Ray’s doctor saying he was confident Ray had COVID-19 and would start treatment based on the protocol recommended by infectious disease doctors at Rowan Medical Center.

About an hour later, Ray had declined and he was being transported to the hospital. Then, an emergency department doctor called. Ray had fallen before he was transported. He was in critical condition and being placed on a regimen as well as oxygen.

The family could call the front desk for information, but Ray could not answer the phone on Monday. A nurse facilitated speaking to Ray briefly. On Tuesday, Ray was able to speak on the phone, but crashed about two hours later and was put under even more intensive care. The family received a call from a palliative care doctor on Wednesday, who told them Ray’s condition was worsening and his kidney functions had dropped by half since he was admitted.

The next call was from an ICU doctor to say the pneumonia was worse and they were applying special oxygen. The family then received a call from a nurse saying there would be a follow-up call.

The last call was from a doctor asking the family if they wanted to do a video call with Ray because he was not going to make it. He was confused and it took a while to understand he was speaking to Pat. Ray could speak, but it was difficult for him.

“We did get to have a very short conversation,” Pat said.

About an hour later, a doctor called for permission to give Ray some medicine to comfort him. Ray died shortly after.

Pat said the family was never able to meet the people who took care of Ray in the hospital.

“But we’re so grateful for what they did for us and for Daddy,” Pat said.

The pandemic impacted the family’s ability to hold a funeral for Ray as well.

Pat said Ray was, in general, in good health, with a strong heart and good upper body strength — enough to pick himself up out of his wheelchair.

“Dad had worked hard all his life,” Pat said. “He was a strong man.”

Part of why Ray wanted to go into a nursing facility so he could work toward walking again. He was determined to work at it from 2017 until he died.

Johnny Bost said his father never gave up. Ray’s faith got him through devastation and good times. He was the 10th of 12 children, a professional baseball hopeful and spent a career in construction.

Johnny said Ray was thoughtful and willing to help people even when things were lean. Johnny said his father was an honorable person who set an example through his faith, craft and being the best person he could be. His father set an example that stressed doing a job right no matter what — from sweeping the floor to building a cabinet. Johnny said he wished he could have been with Ray in the end, but his father knew how he felt about him.

“He meant everything to me, man,” Johnny said. “My daddy knew what I thought of him, my daddy knew that I was proud of him, that I was grateful to him for what he helped me become.”

Johnny said his parents taught him how to be self reliant, too. He picked up skills like carpentry from Ray, but Velma taught him how to be a good cook and patch his clothes.

“They prepared me to be successful in life, and I’m forever grateful for that,” Johnny said.

Ray was also known for having a bit of a sweet tooth. A running family joke was that Ray planned to find a new doctor if he or she said he was diabetic.

“If you gave him a T-bone or a piece of pie, he’d eat a piece of pie,” Johnny said.

Prior to coronavirus, the family visited Ray and Velma often in the nursing home. Johnny said he would bring food, treats, visit and stay part of their lives. Sometimes, they’d invite other residents who were lonely to their family gatherings.

“The more the merrier,” Johnny said. “If that brought them a little happiness in their life, so be it. That’s what it’s all about.”

Ray’s grandson, Heath White, said Ray never talked much about himself, but he heard a lot of stories. That included tall tales of feats of strength like lifting wheelbarrows full of bricks.

“I started to get a feeling that maybe they weren’t exaggerating so much,” Heath said.

Heath and his brother were once helping Ray lay sub-flooring for one of his houses. It was then when banter turned into a challenge: Ray would lay a sheet of sub-flooring alone faster than Heath and his brother could together. Ray, in his mid-60s and legally blind, held nails in his mouth, set the nails, drove them flush with one swing and flipped the hammer for show.

“It sounded like a machine was doing it,” Heath said.

Ray easily outpaced the brothers. It was then when the two had to eat a bit of crow and believe the fact that their grandfather was exceptional.

Ray had artificial vertebrae implanted in the ’60s after he broke his back. He was never supposed to be able to walk again, but he recovered. Doctors expected the ocular cancer to be the end of Ray, but Heath said his grandfather’s faith carried him through.

Heath said seeing people who do not acknowledge the pandemic and disregard safety precautions like wearing masks upsets him. The disease may not seem real to people until it affects them directly, he said.

Heath said seeing Ray struggle for air and being unsure if he recognized his family on the final video call had a profound impact on him.

“You couldn’t be there. You couldn’t comfort him,” Heath said. “You couldn’t hold his hand and let him know.”

Heath said Ray imparted a strong faith to his family and that there is always a plan through all of the difficult parts of his life.

“When I have what I consider a bad day and I’m struggling, I always think my very worst day has never been close to some of the days that he had,” Heath said. “He never once complained, he never whined or bemoaned his situation. He woke up every day and thanked God that he saw the sun.”