Sport legend: John Paciorek perfect in his brief time in the big leagues

Published 12:00 am Sunday, October 4, 2020

By Mike London

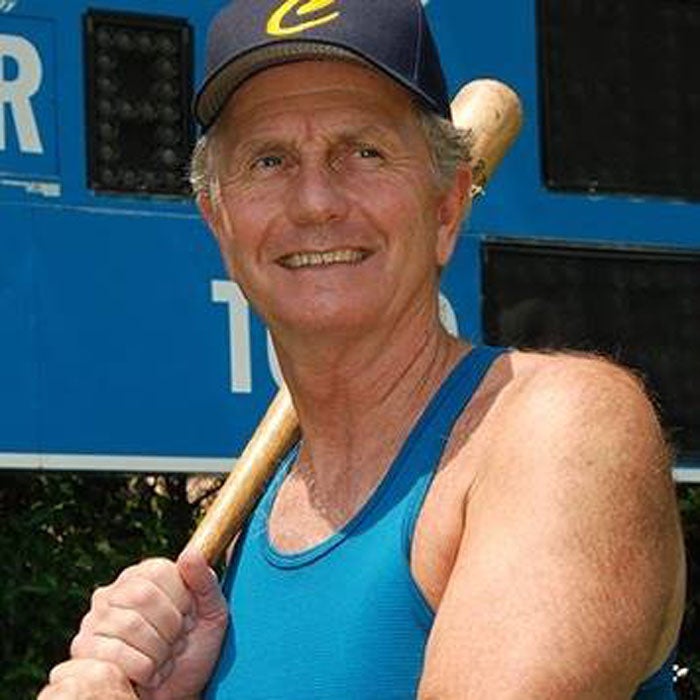

- John Paciorek

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — Every time Sept. 29 comes around, someone mentions John Francis Paciorek, a real-life person who evolved into almost a mythological character.

A legend at 18, Paciorek was perceived as potentially the next Mickey Mantle after one of the most impressive debuts in MLB history on Sept. 29, 1963. He strode to the plate five times for the Houston Colt .45s, who had not yet made the Astrodome their home. He was flawless — three hits and two walks. He scored four runs and knocked in three.

Yet, by the time he was 21, Paciorek was in Salisbury, N.C., playing at Newman Park, his career hanging by a thread in the Class A Western Carolinas League.

Paciorek turned 75 earlier this year, but he is still remembered by some diehard baseball fans as the man who batted a thousand in the big leagues. Books have been written about him. His extraordinary first MLB game — he made running catches in right field in addition to that perfect day at the plate — would also be his last one, his only one.

His story is a reminder of how fragile the human body can be. A physical powerhouse and workout fanatic, Paciorek was unraveled by injuries, starting with a balky back.

If he’d stayed in one piece, who knows? His first pro roommate, Rusty Staub, lasted 23 seasons in the big leagues and smacked 292 homers. Everyone, including Paciorek and Staub, realized that Paciorek was, by far, the more talented of the two.

From the time he was 13, growing up near Detroit, Paciorek was labeled as a special talent by scouts.

By his senior year of high school in Hamtramck, Mi., he stood 6-foot-2 and weighed 200 pounds. He had football scholarship offers from Alabama and Michigan and was All-State in basketball, but his best sport was clearly baseball, where his future appeared unlimited.

This was 1962, and the initial MLB draft was still three years away. Scouts got the promising youngsters signed, but they had to wait until a prospect graduated from high school.

Houston was in its first season as a National League expansion team in 1962 when Houston GM Paul Richards himself headed to Michigan to wine and dine the Pacioreks. He took them out to their first meal at a fancy restaurant. Legend has it that John consumed a steak and when they asked him if he cared for anything else, he said that he’d take another steak.

Paciorek, whose father worked in an automobile factory, signed for $45,000, a ton of money in 1962, a fortune for a 17-year-old.

Paciorek was a dutiful son and turned $15,000 over to his family. He spent $2,000 on the blue convertible he drove down to the instructional league in Arizona. That’s where where he roomed with Staub and drove Staub crazy with his obsessive workout routines. Besides being talented, he was a fanatical hustler. When he was playing right field, he would try to beat the third baseman to the dugout at the end of an inning.

When the 1963 season began, Paciorek was assigned to Modesto, a Class C team in the California League.

That 1963 season was humbling, as he batted .219, but he showed power with nine homers, 15 doubles and four triples in 78 games.

Unfortunately, he hurt his shoulder on a throw. Then he hurt his back doing stretching exercises — hanging from the roof of the dugout — while he was sidelined.

Doctors told him the back pain was being caused by a pinched sciatic nerve.

He was in Houston to see a physician as the 1963 MLB season was winding down. He was asked by one of Houston’s braintrust if he wanted to play in a big league game, as Houston was putting a lot of rookies on the field to try to get the fan base excited about the future. How could Paciorek say no to that opporunity?

On Sept. 27, the Houston Colt .45s actually started nine rookies, the first time that had ever been done in the big leagues.

And on Sept. 29, the final day of the 1963 season, Paciorek, an 18-year-old with an ailing back, headed out to play right field for Houston, as they took on the equally woeful New York Mets.

Paciorek was one of the eight rookies in the Houston lineup. Future All-Stars Staub and Jimmy Wynn were in the middle of the lineup. Stationed at second base was future Hall of Famer Joe Morgan. Paciorek batted seventh.

Paciorek hadn’t played in weeks, but he walked on his first plate appearance in the the bottom of the second inning and scored.

In the bottom of the fourth, with Houston down 4-2, Paciorek delivered a two-run single to left field. He would score on a sacrifice fly.

He had a run-scoring single in the fifth and scored again. He walked in the sixth and scored his fourth run.

He received a standing ovation from the modest crowd of 3,899 when he led off the eighth inning. He got another single, the hardest ball he stroked that day, to go 3-for-3.

Houston won the game, 13-4.

He was given a good chance to make the Houston roster in 1964 and he started off Spring Training with a bases-loaded triple against the Mets.

But his back pain was getting worse, and he struggled. He was sent to the minors and when he couldn’t bear the pain any longer, he underwent spinal fusion surgery. That put him in a back brace for the rest of 1964 and all of 1965. That 1965 season was when the Houston Colt .45s moved into their new home, the”eighth wonder of the world,” and were renamed the Houston Astros.

The spinal surgery helped some, but his back was always tight. That led to lots of injuries.

Paciorek’s comeback after missing a season and a half was planned for Salisbury in 1966 in the Western Carolinas League.

The best team in the league was the Spartanburg Phillies. The second-best team, the Greenville Mets, had the best prospect — Nolan Ryan. He was 17-2 that year with 272 strikeouts.

Salisbury, led by sluggers Danny Walton and Keith Lampard, was awful (44-77) that season and averaged 392 fans per game. The offense struggled so much that 31-year-old manager Walt Matthews activated himself as a player.

Paciorek started slowly. Then he missed a good chunk of May when he headed to the disabled list with back, shoulder and hamstring ailments.

But the rest did Paciorek some good.

He was activated for the May 30 game and immediately swatted a grand slam that helped beat Lexington.

The next night he belted a three-run homer to sink Lexington again.

He stayed warm at the plate in the days that followed, including a clutch, two-run double.

But when Salisbury experienced roster upheaval in the weeks that followed the June draft, Paciorek’s time at Newman Park was over.

He finished that 1966 season in Batavia, N.Y., with disastrous results. He batted .158.

Experimenting with switch-hitting, he went 7-for-79 for two teams to start the 1967 season. That’s when the Astros gave up on their once prized prospect and released him.

Paciorek’s strange story still wasn’t over. He returned to school at the University of Houston — that had been part of his signing bonus — and was watching his younger brother, Tom, play for the Cougars when a Cleveland Indians scout recognized him and offered him a shot at a comeback. He was still only 23. He jumped at it.

In 1968, Paciorek was as close to healthy as he’d been and hit 20 homers in 95 games. He smacked 17 homers for Reno. The other three came with the Rock Hill Indians, as he returned to the Western Carolinas League.

Cleveland started him off in Double A ball in 1969, but then the injury bug bit again — two dislocated fingers and then a torn Achilles tendon. The Indians released him — and this time he was done as a professional ballplayer.

John had two brothers play in the majors. Tom lasted in the big leagues from 1970-87 and had 4,121 official at-bats. Tom was an All-Star with the Seattle Mariners in 1981.

Jim Paciorek played in 48 big league games, all with the Milwaukee Brewers in 1987.

John had two sons who played pro ball, although neither reached the majors.

He was supposed to be Houston’s superstar center fielder for 15 years, but he’s always looked at the bright side. If not for the bad back, he might have gone to Vietnam, and he may not have survived to raise a large family and to coach and mentor hundreds of young ballplayers as a P.E. teacher in California.

Even after all these years, his legacy, his place in the MLB record book is secure.

There have been close to 1,000 players who only played one game in the big leagues.

Of that group, Paciorek holds the records for times on base, runs scored and hits without making an out.

He probably always will.

More Sports

SportsPlus

Braves vs. Mets: Betting Preview for July 27

On Saturday, July 27, Francisco Lindor’s New York Mets (55-48) host Marcell Ozuna’s Atlanta Braves (54-48) at Citi…

How to Watch MLB Baseball on Saturday, July 27: TV Channel, Live Streaming, Start Times

In one of the many exciting matchups on the MLB schedule today, the Cleveland Guardians and the Philadelphia…

How to Watch the Braves vs. Mets Game: Streaming & TV Channel Info for July 27

Spencer Schwellenbach gets the nod on the mound for the Atlanta Braves in the third of a four-game…

How to Watch MLB Baseball on Friday, July 26: TV Channel, Live Streaming, Start Times

Today’s MLB schedule has plenty of excitement, including a matchup between the Cleveland Guardians and the Philadelphia Phillies.…

How to Watch the Braves vs. Mets Game: Streaming & TV Channel Info for July 26

Austin Riley and Jeff McNeil will take the field when the Atlanta Braves and New York Mets meet…