Donaldson’s art has evolved since he was first black man to join Rowan Art Guild

Published 12:02 am Friday, March 6, 2020

By Maggie Blackwell

For the Salisbury Post

James Donaldson’s art hangs at the University of Delaware and in collections up and down the eastern seaboard; he’s exhibited in New York City and even has a hardback book about his collection. Yet he’s about the humblest person you’ve ever met.

“Everything I made,” he says, “my parents would say, ‘How pretty.’ As it started to flow through the community, everyone would call me the artist or the professor. When they needed something, they’d call me. It was a beautiful gift. I knew it was a gift when people would give me money for it. When collectors came from New York, I knew there was something special about my work. It’s really God’s work. I am the vessel. He has given it to me for a short while, and I’m delighted over it. It was innate.”

It really started, he says, in the first grade. Donaldson, already a strong reader, got in trouble for talking when he finished his work early. His first-grade teacher, seeing that he needed a challenge, prepared finger paints and paper for him to use after his work. The paints were “slick like jelly,” and he created paintings there.

Donaldson, 75, recalls names and character traits from his childhood like it was yesterday. He grew up in the Lake Norman area, and recalls neighbors clearly. Cora Robinson was the town baker. Miss Lily was like a storehouse for Jesus; everyone at church would ask, “Did Miss Lily make this?” He recalls smelling cantaloupes before seeing the field, and the sweetness of watermelon, saying they just don’t grow so sweet anymore.

The community at Lake Norman was supportive of Donaldson, helping him through college and lending a hand when his child was born. “I always wanted to please them,” he says. “Not to disappoint them. I try to be as right as I can.”

He’s written a book about the community and the people. “If God wills,” he says, “I’ll publish that book.”

He attended Livingstone College, majoring in French and English. He recalls professors and staff by name. When he wanted to travel home every weekend, Dean Tulane told him, “Oh, young man, you need to be here. This is about your life to come, not the life you grew up with.” Students were required to attend vespers every Sunday, dressed a certain way. The dorm mistress, Mrs. Taylor, required their rooms be immaculate. If it wasn’t, she would come later to check again.

“They hired excellent educators and groomed young people for life. That’s what Livingstone did for me,” he says.

He student-taught under local teaching icon Esther Marioneaux, who proved to be a mentor to him throughout his life. When young female students began to flock to his classroom, Marioneaux would advise them that “Mr. Donaldson is busy preparing his lessons. You need to attend to your studies.” Donaldson says he didn’t realize it at the time, but she was protecting him from any unfortunate incident that might arise. He laughs as he recalls the day he wore red socks to work. Marioneaux made sure he wore dark socks after that.

Marioneaux served as his wedding director and organist. In 1966, he considered buying a black Plymouth. “Oh, no,” Marioneaux advised. “You are young. You need something light.” He bought a canary yellow Mustang, and everyone in town wanted to ride in it or drive it.

Marioneaux and her husband Harold welcomed Donaldson into their immaculate home, often preparing gumbo for him.

“I will always love her,” he says. “A lovely woman and a master teacher. She was such an inspiration to me.”

Donaldson was also influenced by Fred and Raemi Evans. With Fred’s guidance, Donaldson navigated the early days of teaching at Boyden High.

His first really big sale was W. J. Walls, the bishop at the AME Zion churches. Donaldson was commissioned to paint murals for three different churches. He painted a mural as well for Heritage Hall on the Livingstone campus. The building is closed today.

Local storyteller Jackie Torrence had a collection of Donaldson’s work, as did SBI agent Albert Stout. When Stout first walked in, Donaldson says, he insulted his work, his home, and his teaching style. “Just get out of my house,” Donaldson said. Stout burst out in laughter: “Oh, man, I’m just hassling you!” After that, he bought many pieces, often meeting Donaldson for lunch or breakfast. At one point, he requested a painting called, ‘Sunday Morning.’

“I thought of two ladies,” Donaldson says. “One is attentive. The other is asleep.”

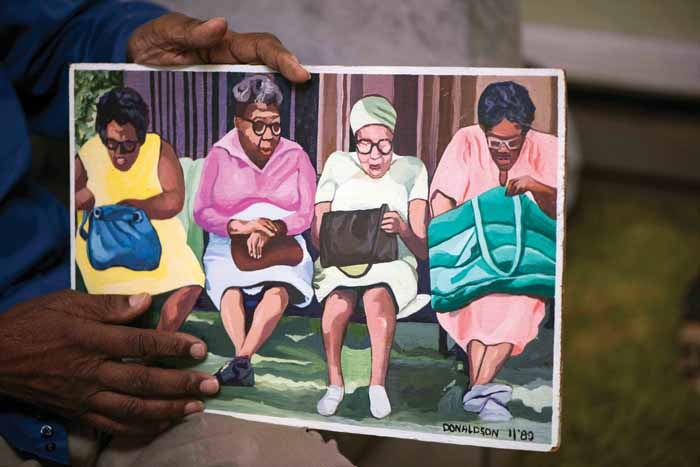

Another painting depicts five ladies seated on a bench, as if waiting for a bus. Some are thin, some are heavier. They’re dressed in different colors and all are searching through their handbags. The painting is entitled, “It’s in Here Somewhere.” He says the original was about four feet in length and hangs in a collector’s home in Chicago.

Donaldson joined the Rowan Art Guild in 1966, becoming the first – and only – black man in the organization. He painted with Kaneko McNeill, Lou Clement, Lloyd Hill, Janie Allen, Betty Sedberry, and Clyde. He wasn’t uncomfortable, he says, because they embraced him and his art.

He’s exhibited at Rowan History Museum and is thankful for the opportunity. “When your own embrace you,” he says, “that’s the best. I can’t describe the feeling. I was delighted each time I was asked. It’s an honor to do it.”

In 1968 Donaldson was approached by Paul Jones, a black curator, very well-known in larger cities. He traveled inside and outside of the U.S., collecting black artists of promise. “I like your work,” Jones said. “Will you do me a collection?” Donaldson said no, art supplies are very expensive. Jones gave him a blank check and advised him to buy anything he needed to develop a collection.

Donaldson laughs as he recalls he spent about $30 on paints and turned out 30 good paintings. They had the exhibit and Jones forwarded the exhibit to the University of Delaware. At the time, Donaldson says, it was the largest single exhibition of black artists’ paintings.

He was also featured in Jet Magazine in 1968, along with Dr. Samuel Duncan.

His art has evolved over the years. A black and white drawing of Marian Anderson dating back to 1968 could be a photograph. It hangs in the University of Delaware. A black and white painting of neighbors Mr. and Mrs. White is also hauntingly realistic, reflecting the foreground in Mrs. White’s glasses.

Today Donaldson’s work, while still realistic, is more surreal. He selects features to highlight, making them larger than life or impossibly one-dimensional. A recent painting of a man playing the guitar shows all four fingers as well as the thumb flat on the fretboard. Others paint black men with large faces, out of scale to the body.

It’s all to make a point, he says, as he explains the works. His 2020 pieces focus on fathers and children. He’s concerned, he says, for families to have dads. That daddy helps the child to do what is right.

“When I think of my life now, it’s important that I leave my legacy. You have black artists today. I was among the first in our community.”

What lies ahead? “I think – and I base it on God, because he orders my steps,” he says. “he’s the first I talk to every morning. ‘Thank you, God, for another day, for my health and for my gift, which is art. What is Your will, have me do it.’”

He treasures a cup from Cohen Galleries in New York with his image on it, and the hardback book that accompanied the exhibit. He recalls his painting of his mother. It sold at Cohen and he’s thankful.

“I think people will continue to want my offerings,” he says. “By being so free spirited with my art now, a lot of good things are going to happen.”

“If I had a message for young people today, I would say, don’t give up hope that success is out there for you. When one gives up hope, that’s the end. Do things that are right, because in the end it will prove a good thing.”

“Everything has a time and a season. When I look back at my life, it was all planned. God knew what was ahead for me.”