All hail North Carolina’s fine ‘shine

Published 12:00 am Thursday, November 14, 2019

By D.G. Martin

Moonshine has come to my rescue.

I am always trying to find ways to make North Carolina Number One in something important.

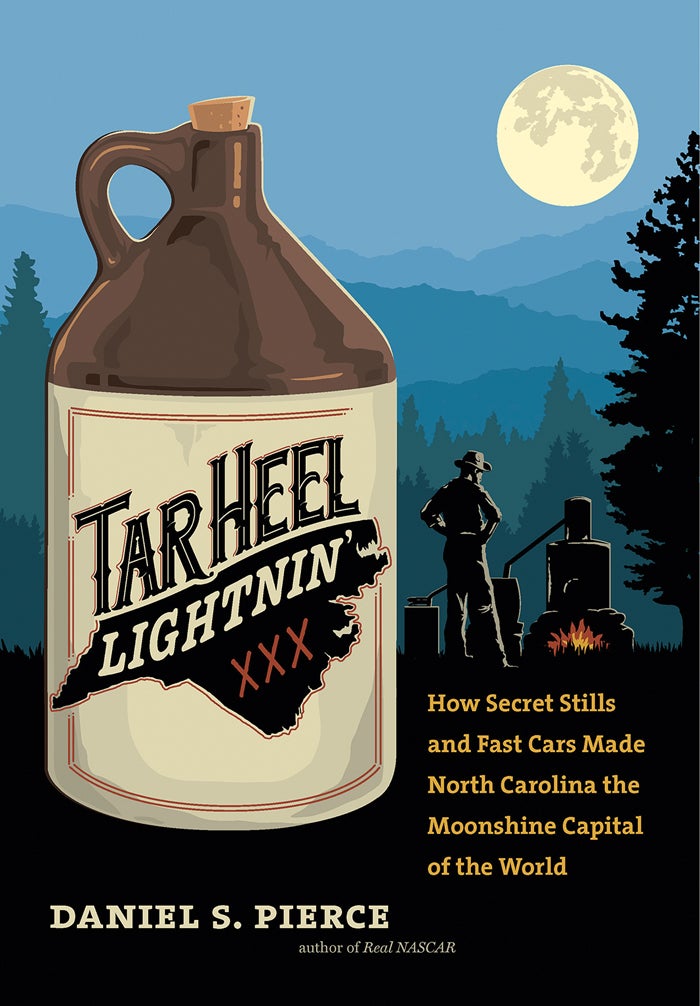

Thanks to University of North Carolina at Asheville Professor Daniel Pierce, we have a substantial claim to be Number One. In his new book, “Tar Heel Lightnin’: How Secret Stills and Fast Cars Made North Carolina the Moonshine Capital of the World,” he asserts that our state is tops in moonshine.

He writes, “Indeed, if North Carolina has ever held the distinction of being number one nationally in anything, it is in moonshine production.”

Then, in about 275 pages, showing the long and rich history of the making, sale and consumption of illegal liquor, he shows why and how North Carolina developed its number one connection with what we call moonshine, also known by other names such as corn liquor, white lightning, blockade, home brew and a host of other terms.

“From the earliest colonial times, farmers, using techniques their families had learned in the British Isles, distilled their corn and fruit into whisky and brandy.”

Until Civil War times, no government restrictions prevented them from making alcoholic beverages to trade or sell. In 1862, the national government passed an excise tax on liquor. After the Civil War, most farmers and other small producers ignored the tax, continued their production and made themselves petty criminals. Federal tax collectors tried to catch these moonshiners and put them out of business and into jail.

The high cost of tax-paid liquor made the production of untaxed moonshine more profitable and more prevalent in every part of North Carolina.

The prohibition movement was growing. In 1909 the state implemented statewide prohibition. Then in 1920, national prohibition went into effect.

Pierce says, “Prohibition only increased the market for moonshine in the state and kept the state in the forefront of illegal liquor production nationally through the 1960s.”

As legal liquor became more available, this shine on moonshine dimmed.

Pierce’s great storytelling gifts make his thorough study of moonshine a fun read.

For instance, he gathers short articles on legendary personalities into a hypothetical “North Carolina Moonshine Hall of Fame (and Shame).”

My favorite of Pierce’s Hall of Famers is Percy Flowers. He was born in 1903 and grew up in Johnston County on a farm near the community of Archer Lodge. He left home at 16 to get away from an abusive father. He learned the liquor making craft from an African American expert and parlayed that expertise into a multi-million dollar enterprise. He was an organizer, hiring others to make the moonshine while he managed the distribution.

I first heard of Flowers from Lynwood Parker, owner of the White Swan Bar-B-Que near Smithfield. Flowers once owned the building where White Swan is today. Ever since, I have been eager to learn more about Flowers. Pierce has obliged.

Flowers entered the business about the time the 18th Amendment’s national prohibition began in 1920. He told people he made more money during those prohibition years than any other period of his life.

Pierce writes, “He was successful not only in making a fortune, producing and selling illegal liquor but also, especially given his high profile, in evading law enforcement.”

Flowers is joined in the Hall by famous figures such as Junior Johnson, the legendary race car driver who learned his trade driving moonshine in cars fast enough to evade the revenuers. Others include Rhoda Lowry, the widow of Lumbee hero Henry Berry Lowry and modern media figures, Popcorn Sutton and Jim Tom Hedrick, who had brands of “legal moonshine” named after them.

There is more, so much more. So if you are looking for a Christmas present for a hard-to-give friend or family member, “Tar Heel Lightnin’” could be a good option.