HS Football: The game has kept Rodney Callaway young

Published 12:05 am Tuesday, August 20, 2019

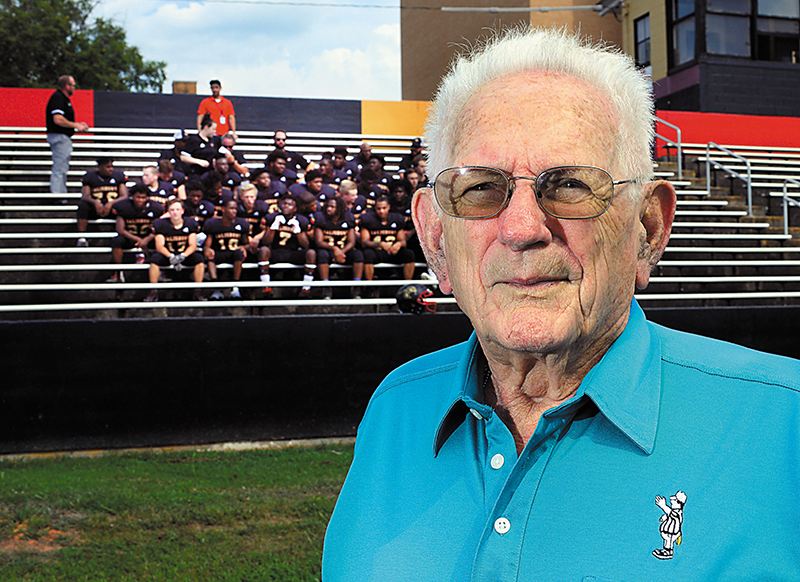

- Rodney Calloway , 88 years old, played in the first game in the Salisbury stadium. The 2019 Salisbury High team is seated behind him waiting for a team photo. photo by Wayne Hinshaw, for the Salisbury Post

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — Rodney Callaway, 88, is the last survivor of the Boyden youngsters who played in the first game in the Salisbury football stadium that opened in 1949.

It’s an iconic venue we now know as Ludwig Stadium.

“I’m the last of the Mohicans,” Callaway said.

Seventy years ago, football looked much different. Center A.L. Gobble handled snapping duties for the Boyden High Yellow Jackets, but he wasn’t positioned in the middle of the line. The line was unbalanced. Tackles Jerry Kincaid and Bruce Rendleman lined up next to each other. Four men were on one side of Gobble, with two on the other.

Quarterback was the least glamorous position. Boyden QB Don Godwin might sneak the ball once in a while, but mostly he was a blocking back, a concussion waiting to happen, a human battering ram. He sacrificed his body to block for tailback Bob Gardner, the speedster who received shotgun snaps from Gobble, and rugged fullback Jerry Barger, who got the lion’s share of the carries and touchdowns.

Ends Callaway and Page Lyerly occasionally ran a route and caught a pass from Gardner or Barger, but mostly their job was to block. Wingback Bob Ritchie lined up just behind the line, off Calloway’s right shoulder, eager to deliver a crunching, double-team block on an unfortunate defensive end.

Undersized but feisty guards, Bill Peeler and Wayne Harrelson, did what guards still do in 2019 — punishing, thankless work next to the center.

This was single-wing football, invented by Glenn “Pop” Warner and sharpened by coaches such as Boyden’s Bill Ludwig.

The football world was evolving in 1949. The double wing and the T-formation, with a play-triggering quarterback under center, had advocates, but Ludwig, a fullback at High Point College before he was hired to coach Boyden football, wasn’t worried about fixing something that wasn’t broken. Come hell or high water, his teams would stick with the single wing.

“It was very basic football — 4 yards and a cloud of dust,” Callaway said. “What Coach Ludwig said was gospel. We blocked and we tackled well. We relied on execution, on double-team blocks and being physical and we had a lot of guys who could hit bigger than their size. We practiced, we drilled, we worked on fundamentals, so we could limit mistakes. Coach Ludwig might forgive you for a defensive penalty from being overly aggressive, but not for an offensive penalty, not for a mental mistake.”

The shiny, 3,500-seat stadium was supposed to make its debut on opening night in 1949 when Boyden played Lexington, but as destiny would have it, delays occurred. The stadium would be christened instead by a visit by the Charlotte Central Wildcats, considered by some sportswriters to be the finest team in the state.

Ludwig had asked for a football facility since he became Boyden’s head coach in 1935, but economic times were tough in the 1930s. Then World War II came long. Ludwig’s team went 8-2 in 1942, but that was his last season at Boyden before he entered the U.S. Navy and became an active part of the war effort.

Boyden’s football program collapsed in Ludwig’s absence and went 0-9 in 1945, but Ludwig returned from the war in 1946. Boyden, the smallest school in the state’s fiercest conference, quickly became stout again, able to go toe-to-toe with Grimsley, R.J. Reynolds and Asheville, among others.

In 1946, the city of Salisbury began its drive to make the vision of a new football stadium a reality. Cost for the stadium lights was set at $7,500. The Salisbury jayvees took on the job of raising the necessary funds.

Salisbury’s leadership announced the new stadium could also be used by the football team at J.C. Price High, Salisbury’s school for black students, because the stadium was a city-wide effort to benefit all citizens.

For 1949, in North Carolina, that was admirably progressive thinking.

The stadium itself was ready on time for the 1949 football season. Granite Quarry contractor W.F. Brinkley saw to that. His crew finished 20 days ahead of schedule.

But installing the state-of-the-art lighting system — that was a hold-up. The Jaycees had raised the $7,500 they promised, but by 1949, those lights cost $10,500. Some bright mind came up with a solution — 600 fans would be asked to pay $5 each for special reserved seats on opening night. That’s how the additional $3,000 was raised.

With the stadium still dark. Boyden’s scheduled opening game vs. Lexington in mid-September was shifted from Salisbury to Lexington’s Holt-Moffitt Field. Boyden won 13-0.

Boyden was on the road the following week and prevailed, 13-0, at Gastonia.

Boyden was idle the last week of September, but there were assurances that the lighting system would be completed in time for Boyden’s third outing — at home against Charlotte Central on Oct. 7.

The open week meant extra time to prepare for a powerful opponent. Charlotte Central was 5-0 and had whipped three N.C. foes, as well as North Charleston, S.C., and Atlanta’s Brown High.

“We still didn’t put in anything unusual for Charlotte Central,” Callaway said. “We knew they were good, but we were just going to do what we did. Some said they were unbeatable, but we were kids and we were 2-0, so we thought we were unbeatable, too. Looking back, Charlotte probably was better. They were the more talented team, the bigger team, the team with more subs, but we believed in Coach Ludwig and Coach M.L. Barnes (assisted by Joe Ferebee and Derwood Huneycutt). And we had a very good athlete in Jerry Barger. Jerry was our hero.”

Charlotte papers got people fired up. “The Charlotte boys probably won’t get their hair mussed up,” one reporter wrote. Needless to say, that quote found its way to the Boyden locker room bulletin board.

Boyden’s offensive starters also were the defensive starters. Boyden’s defensive alignment was a 6-2-2-1. That sounds bizarre, but it was a great defense against the run.

“We didn’t throw much, Charlotte Central didn’t throw much — no one threw much,” Callaway said. “If they did throw it, we had faith in Gardner, the safety. He could cover a lot of the field.”

Boyden had a near disaster during the week. Lyerly and Peeler crashed head-on in a tackling drill, and it was feared both had suffered a concussion. But they were declared fit for duty a day before the game.

Ludwig knew Charlotte Central’s attack was going to be concentrated on battering Boyden’s ends — turning the corner with sweeps against the 175-pound Callaway and 165-pound Lyerly — or simply running over them.

Carrying the ball most of the time for Charlotte Central was Larry Parker. He was big, fast and good. Like Barger, Parker was a junior. He would be Barger’s teammate in the 1950 Shrine Bowl. Their rivalry would continue in the college ranks, with Barger at Duke and Parker at UNC.

When game day arrived on Oct. 7, there were weather concerns. There was talk of postponement, but the rain held off, at least for a while. Gates opened at 6:30 p.m. A ceremony to open the stadium was held at 7 p.m. The stadium was dedicated as a memorial to those who had given their lives in World War II.

“There also was a funny moment,” Callaway said. “The superintendent, J.H. Knox, was getting ready to speak, and suddenly there was this huge roar from the stands. Knox thought for a second it was for him.”

It wasn’t. Boyden’s players had just entered the stadium.

Shortly after the 8 p.m. kickoff, the rain arrived. It was a downpour. It didn’t stop the rest of the night.

“Charlotte Central had come prepared for bad weather, special cleats and decked out in rubber football pants,” Callaway said. “Coach Ludwig reminded us those rubber pants were going to get hot as the game went on. He said they’d lose their legs.”

Neither team scored in the first half. Charlotte Central pushed to the Boyden 11 once, but Lyerly and Callaway were holding their ground, forcing plays back inside where there was all kinds of help.

“Bill Peeler was a good player, an unsung star, and that night he was at his best in the middle of our line,” Callaway said. “Lyerly and Gobble had fantastic games. We started realizing we could handle Charlotte Central up front, offensively and defensively.”

Only one Boyden starter weighed 200, but Boyden put together several first-half drives and controlled the ball.

At halftime, the Boyden players changed their attire.

“We had two sets of shoes and we’d worn our practice shoes in the first half,” Callaway said. “At the half, we switched to our game shoes. We also changed into dry uniforms. The only thing we couldn’t change was our pads.”

It was still 0-0 late in the third quarter. Charlotte Central was trying to throw by then, but with limited success.

Then Boyden made the critical play it needed. Late in the third quarter, Peeler and Kincaid blocked a punt by Parker. Lyerly fell on the ball at the Charlotte Central 44.

By the time the fourth quarter began, Boyden, relying mostly on Barger, was driving at the Charlotte Central 18. Barger carried to the 10, and then to the 4 for first-and-goal.

On second-and-goal at the 1, Boyden’s linemen shoved the Wildcats back, and a limping Barger tumbled into the end zone for what would be the only score of the night.

“The play call was 34, the 3 back (Barger) through the 4 hole (behind the two tackles),” Callaway said.

Charlotte Central was held to 121 rushing yards and 3-for-13 passing for 31 yards. Boyden rushed for 151 yards and threw for just 12. Both teams lost one fumble. Boyden had only 25 yards in penalties, while Charlotte Central had 50.

Legend has it that Boyden players carried a comb and brush to the Charlotte Central sideline when it was over — just in case any of the Wildcats had mussed their hair.

While stadium capacity was 3,500, the estimated attendance on that historic night was 5,500, with lots of the fans making the trip from Charlotte.

“Just a thrilling night, with a lot of things going our way,” Callaway said. “The rain helped us. The crowd’s backing helped us because we didn’t want to let them down. And we played hard for each other. The guys who were in that game played not just for themselves but for the other guys who came to practice every day and helped us prepare. And we played for all those players who came before us, but didn’t get play in that stadium.”

The effort expended in the epic clash with Charlotte Central took a toll on Boyden. Boyden lost, 26-0, to High Point the following week, but it got back on track and finished 7-2-1.

In 1952, Salisbury’s J.C. Price High won the first state championship at the new stadium, defeating Tarboro’s Pattillo High in frigid conditions.

In 1954, Barger would be the ACC Player of the Year and would finish his college career by quarterbacking Duke to a smashing victory over Nebraska in the Orange Bowl.

In 1955 and 1957, Boyden, with Ludwig’s single wing still operating, would roll to NCHSAA state championships. Facing health problems, he retired from coaching in the spring of 1959 with a record of 129-68-11.

Ludwig died when he was 51 in 1960.

In ceremonies on Sept. 6, 1968, Boyden’s stadium was officially dedicated as William S. Ludwig Stadium. A host of Ludwig’s former players gathered for that dedication. Barger, representing all of them, was chosen to speak.

Full integration was achieved in Salisbury in 1969. In 1971, Boyden High became known as Salisbury High, acknowledging a new era. Boyden Yellow Jackets and Price Red Devils were united as SHS Hornets.

After the Korean War, Calloway came home. He missed football and got involved in officiating. He’s still working today. He’s been an official for 51 years now, 22 on the field, 29 more as an observer and evaluator of officials. He’s helped a lot of young officials along the way, and he’s proud of that.

“Some people prefer pro or college football, but it’s high school football that I love,” Callaway said. “There’s no doubt the game has kept me young. I can still get down and get back up with no problems, and as long as I can do that, I’ll keep working.”

A hard thing about living a long life is hearing about old comrades passing away one by one.

Godwin passed in 2003. Lyerly in 2011. Peeler in 2012. Coach Barnes in 2015. The loss of Barger in 2014 jolted Callaway especially hard.

“I can still see Jerry crossing the goal line against Charlotte Central,” Callaway said. “If I close my eyes, I can see it.”