Natalie Alms: Partisan gerrymandering warrants concern

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, July 9, 2019

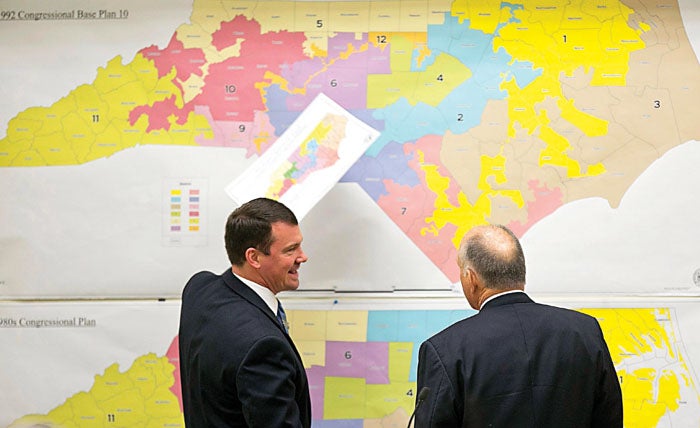

- FILE - In this Feb. 16, 2016, file photo, Republican state Sens. Dan Soucek, left, and Brent Jackson, right, review historical maps during The Senate Redistricting Committee for the 2016 Extra Session in the Legislative Office Building at the N.C. General Assembly, in Raleigh, N.C. Federal judges ruled Jan. 9 and again Aug. 27 that North Carolina's congressional district map drawn by legislative Republicans is illegally gerrymandered because of excessive partisanship that gave GOP a rock-solid advantage for most seats and must quickly be redone. (Corey Lowenstein/The News & Observer via AP, File)

There isn’t a national shortage of potential political crises. Millennials and members of Generation Z might not have Social Security by the time we retire, but we do have our pick of potential anxieties that one might focus on, just like the generations before us.

There’s government gridlock, the national debt, student loans and the list could go on.

I am here to politely add something to it – gerrymandering.

For most people my age, it might sound like a docile enough topic, something that can be dealt with after we deal with everything else. But voting rights shouldn’t just be for political junkies.

Districts set the framework for our democracy by directly affecting how we engage with it and what happens as a consequence in elections and policymaking, so partisan gerrymandering affects all the votes cast in politically gerrymandered states and districts.

Two weeks ago, the Supreme Court decided that North Carolina’s congressional map is not an unconstitutional gerrymander. Moreover, although racial gerrymandering is illegal, the court decided that partisan gerrymandering is a political issue that federal courts shouldn’t get involved in.

Partisan gerrymandering is when districts are drawn to benefit a certain party by putting certain voters into certain districts. It’s not new. North Carolina Democrats did it in the 1990s and 2000s. As technology has made it more precise and effective, Republicans in the state legislature redrew districts in North Carolina in 2010 to benefit their party. North Carolina’s districts have been challenged in courts various times, but the Supreme Court case recently put the problem out of the hands of the courts. The issue is getting more news coverage and attention from political candidates, but I hope that it is recognized as a problem in the long term.

In 2018, 13 House seats were up for election in North Carolina. Because of partisan gerrymandering, Republicans claimed 10 of those, despite the fact that their candidates only received 50.3 percent of the votes.

This imbalance has serious consequences beyond who sits in our state or national legislature. When Donald Trump tweeted in 2016 “THE SYSTEM IS RIGGED!” he wasn’t referring to gerrymandered districts, but that sense of disillusionment with the government itself still rings true today.

In 2016, many of my friends didn’t vote. You would think that college kids at Wake Forest University would be politically engaged and active, but some of them told me outright that they didn’t think their vote would make a difference. Dismal voter turnout statistics echo the sentiment. The 2018 state legislature election in North Carolina was 49.3 percent, and that was high.

When you factor gerrymandering into the argument of my non-voting friends, it’s easy to understand. When districts are gerrymandered to benefit certain parties or candidates, it appears to dilute the power of certain voters.

Voting rights shouldn’t be a partisan issue, although responses and attitudes towards it may be divided across the aisle. I insist that this is a question of democracy writ large, bigger than any certain party or agenda. It calls to our highest ideals of equality of opportunity and civil rights to be full citizens in our nation.

Questions of voting rights pepper the entire history of the United States. We’ve had such large ideals from the beginning such as the premise that people are created equal and have unalienable rights. Time and time again, political rights have been withheld to certain groups and extended after protest.

Isn’t that process of redressing a former wrong, of rising to our highest ideals, truly part of the American story?

Moreover, it just doesn’t make sense. We don’t seem to tolerate sports cheating scandals or college admission scandals, and that’s the same idea of using the system, or changing it fundamentally in a way that advantages you.

A system that prioritizes some votes over others directly leads to people being disillusioned and disengaged. Although it may help one party in the long run, it ultimately helps no one by going against our own ideals.

Protecting voting rights can be one part of fixing this disillusionment for all Americans and tapping into younger voters as engaged citizens. And those same young people can hopefully be part of pushing for that change.

Natalie Alms is a news intern for the Salisbury Post. Email her at natalie.alms@salisburypost.com