Colin Campbell: Weak response shows need for finance reform

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, April 16, 2019

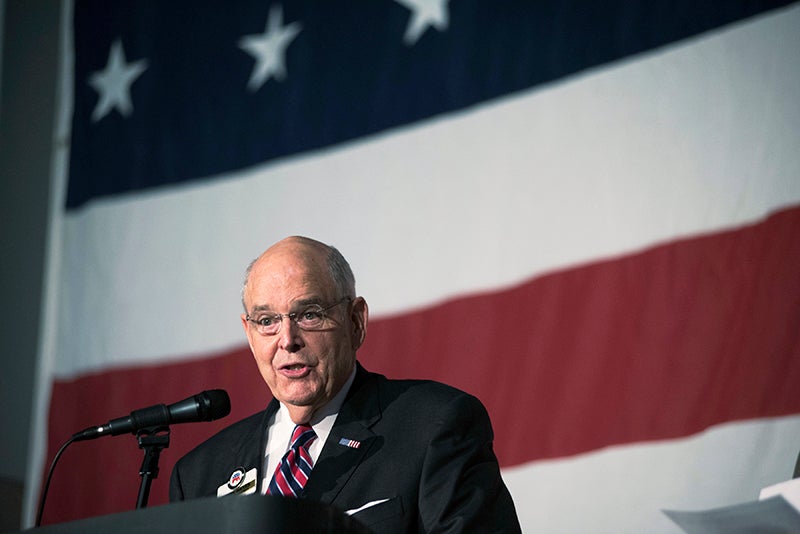

- FILE - In this June 3, 2017 file photo North Carolina Republican Party Chairman Robin Hayes speaks during the North Carolina Republican Party State Convention at the Wilmington Convention Center in Wilmington, N.C. Hayes won't seek re-election to the post after all, the former congressman announced Monday, April 1, 2019. (AP Photo/Mike Spencer, File)

By Colin Campbell

The bribery scandal that has ensnared N.C. Republican Party Chairman Robin Hayes couldn’t be a more perfect example of how big money can corrupt state politics.

Hayes was recently indicted on charges that he’d worked with insurance company executive Greg Lindberg to bribe the state’s insurance commissioner with campaign money in exchange for regulatory actions favorable to Lindberg’s companies.

Lindberg had become the NCGOP’s largest donor, but he also wrote big checks to support Republican Lt. Gov. Dan Forest, the N.C. Democratic Party and multiple members of Congress and the state legislature.

The indictments offered a perfect chance for politicians to wash their hands of potentially dirty money and propose campaign finance reforms. Instead, the reaction from many of the state’s leaders has been pathetic and uninspiring.

While several congressmen who took Lindberg contributions announced plans to donate the money to charity, the two state political parties have made no such promises. Apparently they like having money, and they don’t really care who it came from.

Political groups associated with Forest haven’t given money back. While the lieutenant governor said he’s troubled by the indictments, he also told WRAL that “these are good guys, I like these guys.”

Democrats gleefully pounced on the indictments as an example of Republican corruption, but it’s hard to take the moral high ground when your party is keeping big money from the alleged bribemaster.

And when your party’s chairman, former insurance commissioner Wayne Goodwin, got help from Lindberg in his 2016 campaign, is accused of taking regulatory actions that favored Lindberg companies, and did consulting work for Lindberg after leaving office.

Goodwin has been declining most interview requests but hired a public relations firm to issue statements that “I do not recall being asked to take or direct any action to help Greg Lindberg or his companies during my time as insurance commissioner. Any suggestion that I have ever taken any action in return for contributions is categorically false.”

Unfortunately for Goodwin, defenses that begin with “I do not recall” are never particularly convincing. The bare minimum response for any politician or political group that got contributions from Lindberg would be to give the money to charity — and call a news conference to answer questions about their relationship with the indicted businessman.

That hasn’t happened, and I think it’s because the sort of arrangement that Hayes allegedly brokered is common in state politics. You or your company’s political committee write a check to a politician, and then you later ask them to support legislation that helps your business.

It’s generally legal as long as you don’t explicitly state that your money comes in exchange for certain actions. Hayes got in trouble because, according to the indictments, he was blunt in describing the arrangement to insurance commissioner Mike Causey — and Causey happened to be recording the conversation for federal investigators.

State political party organizations are particularly vulnerable to corruption because unlike individual candidates, there’s no limit on how much a single individual can donate. Legislators must immediately impose a limit in order to restore the public’s trust in our political system.

More restrictions also should be placed on political action committees and dark money “nonprofits” that run political ads. State lawmakers might find their hands are partly tied by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling on campaign money, but it’s worth a try.

In the absence of widespread reforms, individual politicians and parties should just say no to the next shady-looking businessman offering a million-dollar check. The N.C. Senate Republican caucus already set the example: According to a WRAL report, the group declined to take money from Lindberg because it “just didn’t feel right.”

A big check from Lindberg might have helped the Senate GOP keep more seats in last year’s election. But apparently they realized that it’s better to lose an election honorably than win it by selling out your constituents to the highest bidder.

Colin Campbell is editor of the Insider State Government News Service.Write to him at ccampbell@ncinsider.com.