Did crime literature inspire murder in Victorian England?

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 31, 2019

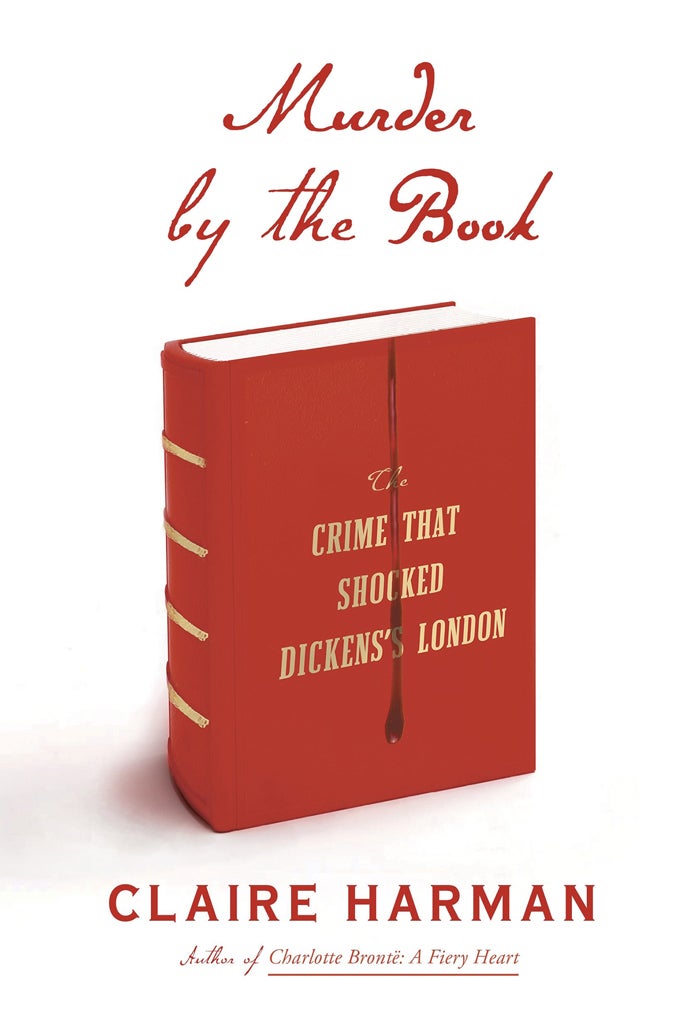

- Murder by the Book: The Crime That Shocked Dickens's London

“Murder by the Book: The Crime That Shocked Dickens’s London,” by Claire Harman. Knopf. 272 pp. $26.95.

By Heller McAlpin

Special To The Washington Post

On a May night in 1840, an asthmatic, hard-of-hearing 72-year-old English aristocrat, Lord William Russell, was brutally murdered in his London townhouse. The crime attracted widespread attention that cut across class lines. Among the interested were rising literary star Charles Dickens, journalist and future novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, and the recently wed 20-year-old monarch, Queen Victoria.

Why were they so riveted, and why, more than 175 years later, was Claire Harman, an accomplished literary biographer, drawn to this true-crime story?

Harman, whose biographical subjects have included Charlotte Brontë and Robert Louis Stevenson, is well-practiced at sifting through the lives of authors in the context of their times and finding relevance to our own. The homicide that propels Harman’s latest work, “Murder by the Book,” hit a nerve among Britain’s uneasy upper classes, but what interests Harman even more is the alarm it provoked about the potentially damaging influence of violent entertainment — a concern still heatedly debated today.

As in her biographies, Harman here demonstrates a flair for distilling reams of research into a succinct, lively narrative. With an appreciation for pithy quotations, telling details and amusing gossip, she’s quick to spot a fascinating aside, like the fate of Dickens’ pet raven, Grip — whose stuffed body was sold at auction after Dickens’ death in 1870 and was ultimately bequeathed by a later owner to the Free Library of Philadelphia, in Edgar Allan Poe territory, where it has remained evermore.

“Murder by the Book” opens with the housemaid’s discovery of her master’s body, “his throat cut so deeply that the windpipe was sliced right through and the head almost severed.” Police find signs of a bungled burglary that raise suspicions of an inside or staged job. Oddities abound: The crime scene is curiously free of blood. The truss Lord William wore for his hernia is askew. A number of gold and silver items are found abandoned by the front door. The house had been ransacked, but many valuable, highly portable objects had been left behind.

Our attention secured, Harman broadens her scope. She reconstructs the victim’s life in broad strokes and revisits his final day, including his last walk through his posh Mayfair neighborhood. She pins him squarely on the social map: “Grandson of one duke, brother to the next two, uncle to the latest, Lord William was doomed to be a satellite male in a family well provided with heirs, and as such of small fortune and no importance.”

Harman also notes that “London in 1840 was teeming with immigrants, the unemployed, and a burgeoning working class who were more literate and organized than ever before.” Class boundaries were changing, and servant turnover rates were high, a constant vexation for the wealthy.

Just five weeks before the murder, Lord William had hired a new Swiss manservant, a 24-year-old former footman, on the recommendation of a friend. In his new master’s relatively modest household, Francois Courvoisier’s duties encompassed those of valet, butler and handyman. He was not quite up to the task, and Lord William wasn’t shy about expressing his displeasure. Courvoisier quickly became the only murder suspect, despite his unflappable cool.

Like the murderer, Harman goes for the jugular in her account of the investigation, trial and aftermath. Unfortunately — and somewhat frustratingly — she is unable to stanch the flow of unsolved mysteries surrounding the case. Inconsistencies and unanswered questions include Courvoisier’s conflicting accounts of the crime and the troubling influence of large monetary rewards on the outcome — which Harman suggests may have led detectives to plant dubious evidence.

She’s on firmer ground re-creating the well-documented, obscene spectacle of Courvoisier’s hanging — which was attended by some 40,000 people, at a time when London’s population was under 2 million. The harrowing experience led Dickens and Thackeray to champion the abolition of public executions, which finally passed in 1868.

As riveting as this true-crime story is, what elevates “Murder by the Book” above sensationalism is its focus on how this case heightened concern over the malevolent influence of violent entertainment. One book in particular was vilified in the aftermath of Lord William’s murder for sparking copycat crimes: William Ainsworth’s 1839 novel, “Jack Sheppard,” along with its numerous, enormously popular, unlicensed stage adaptations.

Based on the exploits of a notorious early-18th-century thief and jail-breaker, “Jack Sheppard” was an example of the true-life outlaw tales dubbed Newgate novels, after the prison. This “felon lit,” which appealed especially to the rapidly expanding market of a growing, literate working class — including Courvoisier — was said to have “glamorized vice and made heroes of criminals” by playing down misdeeds and highlighting dashing exploits. Harman writes that Dickens’ “Oliver Twist,” with its sympathetic portrait of London’s pickpockets and thieves and gory murder scene, was lumped in with this group, which moved the author to shift his focus from crime to contemporary social evils in subsequent novels.

It’s hard not to feel a twinge of nostalgia for a time when literature and drama were thought to wield such power. Over the years, concern has shifted largely from the potential influence of books and theater to that of gratuitously violent TV shows, movies and video games — and criticism is often tempered by worries about the ramifications of curtailing free speech with moral policing. “Murder by the Book” reminds us that the debate has been knocking around for a long time.