The decision that led to decades of Jim Crow

Published 12:00 am Sunday, February 10, 2019

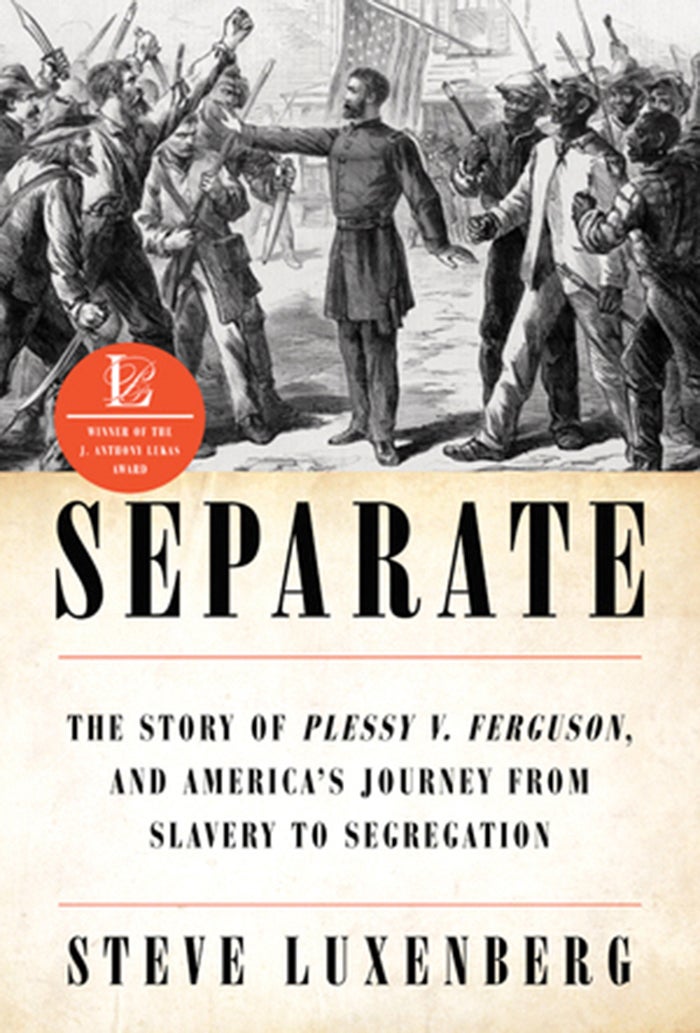

- Separate: The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson, and America's Journey From Slavery to Segregation

“Separate: The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson, and America’s Journey From Slavery to Segregation,” by Steve Luxenberg. Norton. 600 pp. $35.

By Eric Foner

Special To The Washington Post

A few years ago the legal scholar Jamal Greene published “The Anticanon,” an article that identified the worst Supreme Court decisions in American history. High on the list was Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 case in which the court upheld a Louisiana law requiring railroad companies to provide “equal but separate” coaches for white and black passengers.

Legally mandated segregation, the court ruled, did not violate the 14th Amendment’s guarantee to all persons of the equal protection of the laws.

Thanks to the iconic status achieved six decades later by Brown v. Board of Education, which overruled it with regard to public education, Plessy is undoubtedly the most widely known of a series of late-19th-century Supreme Court decisions that eviscerated what Republican leader Carl Schurz called the “constitutional revolution” after the Civil War — the three amendments that ended slavery and sought to establish the legal foundations for equal citizenship regardless of race.

But few Americans know much about the cast of characters central to the case. They include Albion W. Tourgée, who as a judge fought the Ku Klux Klan in Reconstruction North Carolina and argued the case before the court; Henry Billings Brown, a scion of the New England elite who wrote the 7-to-1 decision; John Marshall Harlan, the slave-owning Kentuckian who fought for the Union in the Civil War and became the lone dissenter in Plessy; and members of the Citizens’ Committee of New Orleans, descendants of the city’s prewar mixed-race free black community, who initiated the campaign to overturn the Separate Car Act.

As Steve Luxenberg makes clear in “Separate,” blacks saw the law first and foremost as an affront to their rights as citizens, which, in their view, included equal treatment in places of public accommodation and entertainment, such as hotels, restaurants and theaters, and by transportation companies.

Luxenberg reminds us that campaigns for the right to travel without facing humiliating discrimination long preceded the Civil War and took place in the North as well as the South. With financial assistance from a local railroad company — which disliked the expense of separate cars, since there were often few if any black passengers — the Citizens’ Committee arranged for the light-skinned Homer Plessy to enter a whites-only coach and for the conductor to have him arrested when he refused an order to leave.

Tourgée thought the fact that Plessy could easily have passed for white demonstrated the absurdity of attempting to write racial classifications into law and empowering train conductors to determine a passenger’s race. He also insisted that the law’s purpose was not simply to separate riders but to degrade blacks.

Writing for the court’s majority, Brown did not confront most of Tourgée’s arguments but blamed blacks for being oversensitive. So long as facilities were equal, he insisted, separation was not a “badge of inferiority,” even if “the colored race” chose to see it as such. He went on to muse about the immutable nature of “racial instincts,” the undesirability of “enforced commingling” of the races and how whites’ reputations would suffer if they were forced to sit in the same car as blacks.

In his dissent, Harlan issued the oft-quoted rebuke to the majority: “Our Constitution is color-blind.” The “thin disguise” of equal facilities, he wrote, could not obscure the fact that enforced separation was an expression of racial dominance rooted in slavery and therefore violated not only the 14th Amendment, with its guarantee of equal treatment, but also the 13th, which had irrevocably abolished that institution. The decision, Harlan correctly predicted, would unleash a flood of laws segregating every realm of Southern life.

Of course, separate institutions were never equal. As Luxenberg points out, after Harlan’s death in 1911, Brown admitted that it was “probably the fact” that the Louisiana law had an illegitimate discriminatory purpose. But by then it was too late. For more than half a century, Plessy would provide the legal foundation for the system of racial inequality known as Jim Crow.

Luxenberg, for many years a senior editor of The Washington Post, is a fine writer who tells this story in an engaging manner. To be sure, his apparent desire for novelistic effects sometimes gives the prose a purplish hue.

A more serious problem is the book’s structure, which undermines its narrative coherence. Most of “Separate” consists of alternating biographical chapters about Tourgée, Brown, Harlan and members of the Citizens’ Committee. This produces chronological confusion.

Thus, one chapter ends in early 1862 with Harlan engaged in battle with Confederates. The next one then backtracks to 1847, when Brown helped prevent the capture of a family of fugitive slaves. Later, we learn of Brown’s success in avoiding the draft toward the end of the Civil War, only to find ourselves suddenly with Tourgée at the war’s outset in 1861.

The long biographical excursions are not only unnecessary but often of questionable relevance. They produce significant delay in getting to the actual case.

Two hundred pages elapse before the narrative reaches Reconstruction. Not until four-fifths of the way through this more than 500-page book does Louisiana enact the Separate Car Act. This is a pity, because the best parts of “Separate” consist of Luxenberg’s vivid account of how the Citizens’ Committee and Tourgée developed their legal strategies and how the case proceeded in the Louisiana courts and in Washington.

“Separate” reminds us that our history is not simply a narrative of greater and greater freedom. Rights can be gained, and rights can be taken away. Constitutional guarantees can sometimes, with the acquiescence of the Supreme Court, be violated with impunity.

We live at a moment not unlike the 1890s, with its retreat from the ideal of equality. Just a few years ago the court invalidated key provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a signal achievement of the civil rights revolution that was meant to enforce the 15th Amendment, enacted during Reconstruction.

President Trump recently announced a plan to abrogate the clause of the 14th Amendment that recognizes as citizens virtually all persons born in the United States. With a newly strengthened conservative majority on the Supreme Court, one cannot help wondering which constitutional provision will be next.