Byron York: A day of reckoning for Avenatti

Published 4:35 pm Tuesday, October 30, 2018

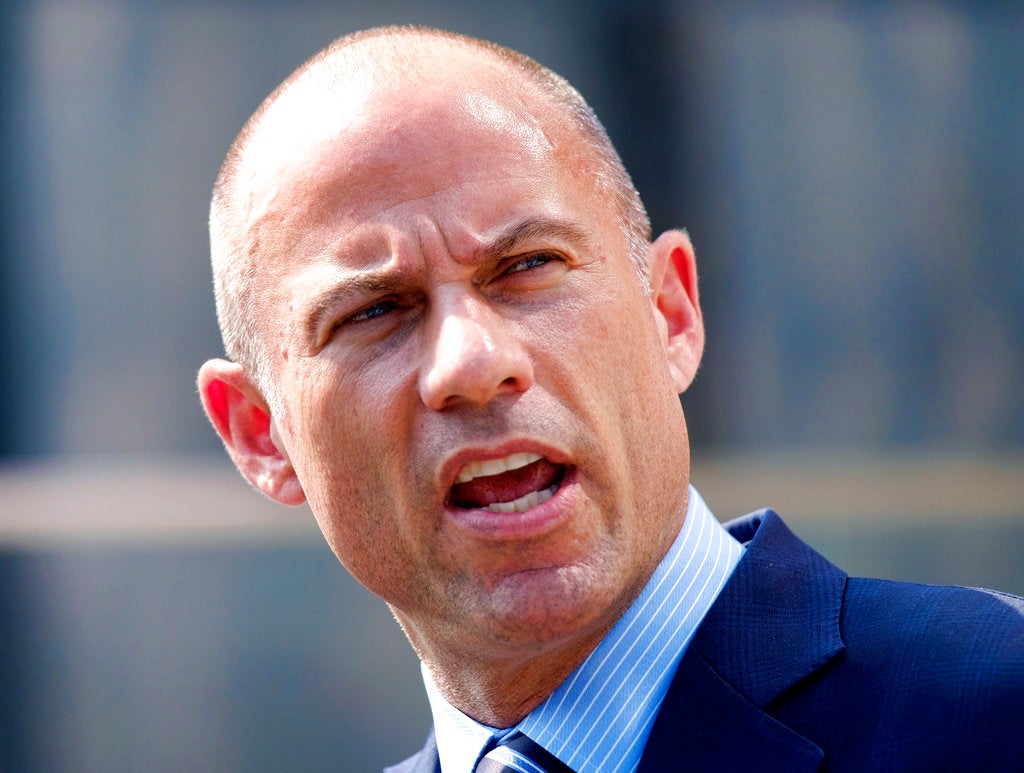

- n this July 27, 2018 file photo, Michael Avenatti, the attorney for porn actress Stormy Daniels, talks to the media during a news conference in front of the U.S. Federal Courthouse in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

Michael Avenatti, the lawyer for porn star Stormy Daniels and a 2020 Democratic presidential hopeful, jumped into the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court confirmation battle on the afternoon of Sept. 23. On that day, The New Yorker had published the allegations of a woman named Deborah Ramirez, who claimed that a drunken Kavanaugh exposed himself to her during a party at Yale sometime in 1983 or 1984. Almost immediately, Avenatti took to Twitter with an allegation of his own.

Avenatti said he had a client, “a woman with credible information regarding Judge Kavanaugh and Mark Judge.” He did not reveal her name.

Within minutes, Mike Davis, chief counsel for nominations at the Senate Judiciary Committee, sent an email to Avenatti. “You claim to have information you consider credible regarding Judge Kavanaugh and Mark Judge,” Davis wrote. “Please advise of this information immediately so that Senate investigators may promptly begin an inquiry.”

Avenatti responded quickly. “We are aware of significant evidence of multiple house parties in the Washington, D.C., area during the early 1980s during which Brett Kavanaugh, Mark Judge and others would participate in the targeting of women with alcohol/drugs in order to allow a ‘train’ of men to subsequently gang rape them,” Avenatti wrote. “There are multiple witnesses that will corroborate these facts and each of them must be called to testify publicly.” Avenatti supplied a list of questions Senate investigators should ask Kavanaugh, and also said he would “provide additional evidence” to the committee in the days to follow.

Of course, it wasn’t true. Still, Avenatti’s allegation poured fuel on an already raging partisan fire over the Kavanaugh nomination. First there was the Christine Ford allegation. Then came the Ramirez accusation, which, coming after Ford, gave Kavanaugh’s opponents the occasion to claim a “pattern” of Kavanaugh’s alleged abuse of women. Then Avenatti’s allegation — gang rape — sent it into another dimension.

Avenatti’s client was identified as Julie Swetnick, who had lived in the Washington area during Kavanaugh’s high school years. Avenatti sent the committee an affidavit in which Swetnick made her claims. Beyond that, he provided no other evidence to support the allegation — beyond the promise of “multiple witnesses.” Nevertheless, Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee took it very seriously.

“In light of shocking new allegations detailed by Julie Swetnick in a sworn affidavit, we write to request that the committee vote on Brett Kavanaugh be immediately canceled and that you support the re-opening of the FBI investigation,” committee Democrats wrote Republican chairman Charles Grassley.

The committee immediately began investigating Avenatti’s claim, using staff time and resources it could have devoted to other parts of the Kavanaugh matter. According to Grassley, the committee interviewed 10 associates of Swetnick, working late nights and a weekend in the process. “Committee staff sought to interview Ms. Swetnick,” Grassley later wrote, “but Mr. Avenatti refused.”

Not long after, NBC aired an interview with Swetnick in which she backed away from her most incendiary accusations. In addition, Swetnick gave NBC the names of four people she said knew about the gang rapes. The network reported that one of the people did not know a Julie Swetnick, another was dead, and two others did not respond to inquiries.

Avenatti also gave the committee a declaration from an anonymous “witness” who said that in 1981 to 1982, she personally saw Kavanaugh “‘spike’ the ‘punch’ at house parties I attended with Quaaludes and/or grain alcohol. I understood this was being done for the purpose of making girls more likely to engage in sexual acts and less likely to say ‘No.'”

Avenatti would not tell the committee who the “witness” was. But, recently, NBC reported that its journalists talked to the witness, who did not back up the declaration that Avenatti gave the committee on her behalf. “It is incorrect that I saw Brett ‘spike’ the punch,” the woman told NBC. “I didn’t see anyone spike the punch … I was very clear with Michael Avenatti from day one.

“I do not like that he (Avenatti) twisted my words,” the woman said.

Putting aside the question of why NBC waited to report the woman’s statement until after the Kavanaugh vote was over, the entire Avenatti episode left Grassley angry that the publicity-seeking lawyer had hijacked the committee’s time and energy at a critical moment, with claims that were obviously untrue. So on Oct. 25, Grassley formally referred Avenatti (and Swetnick) to the Justice Department for a criminal investigation into their conduct.

“It is illegal to knowingly and willfully make materially false, fictitious or fraudulent statements to congressional investigators,” Grassley wrote in the referral. “When charlatans make false claims to the committee — claims that may earn them short-term media exposure and financial gain, but which hinder the committee’s ability to do its job — there should be consequences.”

With Avenatti, there have so far been no consequences, beyond the loss of whatever credibility some cable TV news organizations conferred on him in repeated appearances over the last several months. Now, with the Grassley referral, that could finally change.

Byron York is chief political correspondent for The Washington Examiner.