Ferrel Guillory: Recession left its mark on North Carolina

Published 12:58 am Sunday, October 7, 2018

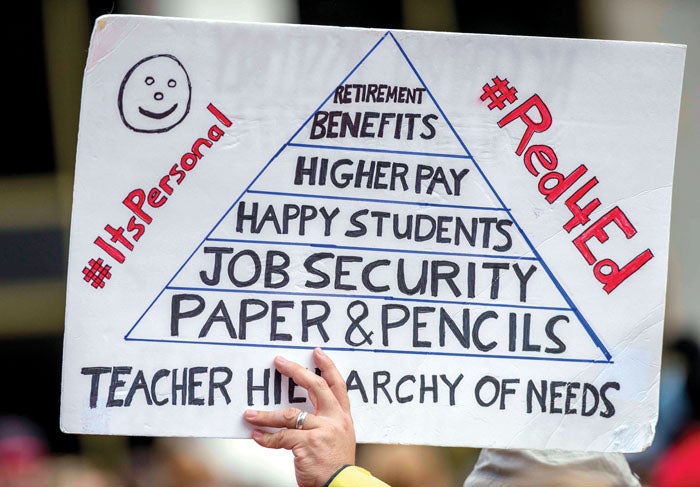

- Teachers and public school supporters rallied in the state capital in May to take a stand in regards to state funding for education. Jon C. Lakey/Salisbury Post

Ten years ago this month, North Carolina had already entered, but hadn’t yet fully descended into, the global Great Recession. By the economists’ definition, the recession started in December 2007 and ended in June 2009. And yet, the state’s educational, civic and political landscape still bear marks of the deep downturn of the past decade.

In October 2008, the state’s unemployment rate stood at 6.5 percent — then it zoomed up to 10 percent only four months later. It eventually peaked at 11.4 percent in February 2010 when more than half a million North Carolinians who wanted to work went jobless. The poverty rate went up from 14.6 percent in 2008 to 18 percent in 2012.

Like the nation, North Carolina has experienced a long, agonizingly slow recovery. Now, as labor market analysts Mike Walden and John Quinterno have pointed out, North Carolina enjoyed a significantly strong period of job growth through the first half of 2018, with unemployment down to 4.1 percent, the lowest since 2000. The poverty rate has declined to 14.7 percent, roughly the same as in 2008.

But it has been an uneven recovery, with only modest private-sector wage growth and with a divide between high-pay and low-pay employment. The recession delivered a coup de grace to the 20th century textile and furniture industries, while the recovery has fostered an economic restructuring.

The state’s major metropolitan areas, especially the RDU and Charlotte regions, have propelled the state in population growth and jobs in the digital economy, business and professional services, pharmaceuticals, and health care. Dozens of rural communities have lost population, some also taking hard hits from hurricane-induced flooding.

The Great Recession appears to have heightened the link between schooling and careers. Parents push their children to follow an educational path that leads to an assured job. Schools respond with more STEM — science, technology, engineering and math — in the curriculum. Community colleges emphasize their capacity to train for middle-wage and higher jobs.

The Great Recession has also stiffened the challenges facing rural schools, especially in recruiting and keeping high-quality principals and teachers. Demographic shifts have left many rural schools filled with children of poor households. Urban districts can offer more in supplemental pay and more schools with students of middle-class, college-educated parents.

The Great Recession also contributed to a dramatic shift in political power and educational policy-making in North Carolina. In 2008, Democrat Barack Obama carried the state in the presidential election, while Democrat Bev Perdue won the governor’s office and Democratic legislators retained a majority in the General Assembly. As the recession deepened, state revenues plummeted by hundreds of millions of dollars over two fiscal years — and the governor and legislators had to cope with keeping the state budget in balance.

The 2010 elections brought a Republican legislative majority to power. GOP legislative strategists mounted a potent campaign in the context of the recession — and their party gained a veto-proof majority in 2012.

Thus, state education policy-making and budgeting over this decade have arisen from Republican priorities and intra-GOP dynamics. A-through-F grades for schools. A third grade reading mandate. More charter schools. State funding for private school students of lower-income parents. Targeted, not uniform, teacher pay raises. State tax cuts that tilt toward businesses and the affluent and curtail revenue growth.

Now, in the midst of an off-year election campaign, the recession figures into the political debate over trends in teacher pay and public school funding. Republican leaders use statistics to argue that schools and teachers gained more over their eight years in power as the recovery advanced than in the previous eight years under Democratic leadership.

The GOP leaders make sure to include the two state budgets that declined precipitously under the weight of the recession. They charge Democrats with mismanaging the dire situation. But they don’t mention that the revenue collapse would have required budget cuts or tax increases no matter who had been in charge.

The counter-argument also uses the recession as a measuring point. Democrats and other GOP critics can point to analyses that show that per-pupil spending and average teacher pay have not returned to pre-recession levels. Teachers have marched on Raleigh to spotlight inadequate pay and instructional resources.

The legislative elections, thus, ask voters for their verdict on education, as well as the economy, post-recession. Think of the question this way: The Great Recession plunged North Carolina 50 feet under water. Has the state risen above the surface? Or has it risen 30 feet or so, higher than during the recession, but still under water?

Ferrel Guillory is the director of the Program on Public Life, professor of the practice at the UNC School of Media and Journalism, and the vice chairman of EducationNC.