Once a ‘Hunger Games’ backdrop, mill village still a treasure for images, memories

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, September 26, 2018

You could say “The Hunger Games” almost destroyed Henry River Mill Village.

But for photographer Clayton Joe Young, poet Tim Peeler and historian Kelly Carroll, the Burke County village’s connection to the popular movie is almost an aside to its real beauty, its true meaning and its place in Southern culture.

Calvin Reyes, one of the new owners of the 72-acre site, also understands the importance of this village beyond the movie.

He sees what is represented in the hundreds of images Young has taken of the place. He feels the words within the scores of poems Peeler has written about it.

“It’s whatever you want it to be,” Reyes says.

With the establishment of the nonprofit Henry River Preservation Fund, Reyes and others envision the village becoming a spot for heritage tourism.

Some day, the site will host festivals, tours, a museum, recreational access to the river, a restaurant and 20 former mill houses offered for overnight stays.

Some of those things, such as tours, festivals, a small museum and regular hours, already are happening.

Most important, Henry River Mill Village will be preserved, which means a lot to people who grew up in this company town and whose ancestors worked at Henry River Manufacturing Co.

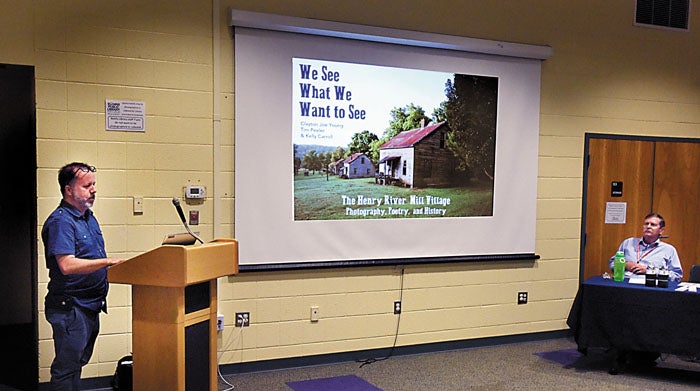

Young, Peeler and Reyes spoke during a program Monday night at South Rowan Regional Library. It was the first in the library’s North Carolina History Series, which also will have programs Oct. 8 on China Grove Roller Mill and Nov. 26 on the 1944 polio epidemic in Catawba County.

Also on hand Monday night was Robert Canipe, editor-in-chief of Redhawk Publishing, a subsidiary of Catawba Valley Community College.

Redhawk published the book “We See What We Want to See” that tells the Henry River Mill Village story through Young’s photographs, about 20 Peeler poems and historical notes from Carroll, who did her master’s thesis at Columbia University on the Henry River locale.

Carroll, who lives in New York, did not attend Monday night. After the program, Young and Peeler signed books that were available for purchase.

An award-winning photographer, Young is an East Rowan High School and Appalachian State University graduate. He serves as program director and senior professor for the photographic technology program at CVCC in Hickory.

Peeler directs the academic assistance programs at CVCC. He has published hundreds of poems, stories, reviews and essays, while also writing 14 books and three chapbooks. Five of Peeler’s baseball books are part of the permanent collection at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Reyes and his mother and stepfather, Elaine and Michael Namour, bought the abandoned Henry River Mill Village property Oct. 6, 2017. Wade R. Sheppard, now deceased, previously owned the land, which included the company store and 20 of the original 35 mill houses.

The site gained notoriety as the home for District 12 scenes in “The Hunger Games,” the film released in 2012.

Because they wanted to be in the same place (the company store) where Peeta Mellark tossed a loaf of bread to Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence’s character), fans of the movie soon started seeking out Henry River Mill Village.

Sheppard, seeing an opportunity to maybe sell his property at a higher price, allowed access to the uninhabited mill village less than two miles from Interstate 40 (in the Hildebran community). One good result was that it led to Sheppard’s giving Young access to take photographs.

“I could finally visit it,” he said.

On his own lonesome visits to the picturesque village, Young said he was struck by the things he saw that seemed out of place — an old television, a book, a toy, a breakfast chair, an angel cutout, a child’s red dress.

He heard the houses creaking and their tin roofs rattling. Bricks were falling to the ground. He sensed that something was following him around, and one day a puppy did just that.

“This place gave me the creeps,” Young said.

Sheppard died, and it led to more people vandalizing the buildings and taking their own souvenirs as “Hunger Games” keepsakes.

“We thought this place wasn’t going to exist in five or six years,” Canipe said.

The salvation came in the purchase by Reyes and the Namours, establishment of the preservation foundation and all the people with ties to the old mill village who wanted to see it saved.

There were yard sales, bake sales and a Henry River Mill Village Reunion, where Young and Peeler hit on the idea of combining Young’s images with Peeler’s poems.

They dedicated their book with Carroll “to the men and women of the Henry River Mill Village who lived and died there, were born there and who still live there in their memories.”

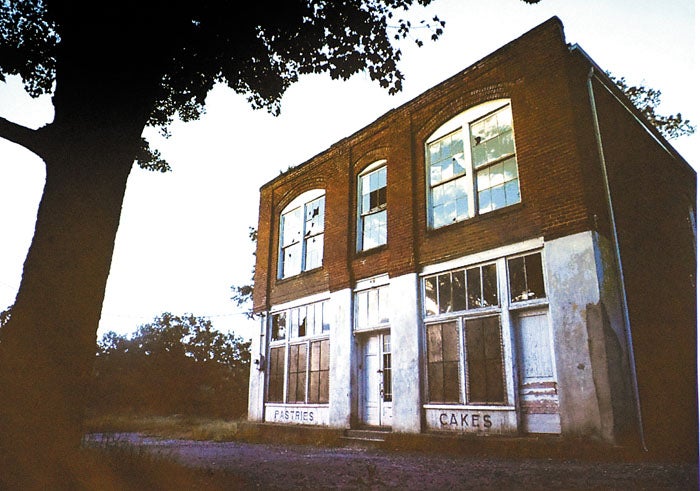

The Aderholdt and Rudisill families opened Henry River Manufacturing Co. in 1905. The three-story textile building produced cotton yarn. The company also built 35 houses for workers, a two-story boarding house, a company store and a dam on the river to produce power.

The homes were on sites of about an acre each — enough room to allow for family gardens and outhouses. The houses were designed to resemble farmhouses, a deliberate attempt to ease the transition for many of the workers who were coming off farms to their first industrial jobs.

Henry River Manufacturing was one of the last industrial sites to rely on water power before converting to steam in 1914 and electricity by 1926. A two-story addition was built in 1935.

At its most productive, the mill employed 160 people. Workers lived in the houses rent free until 1933 and were reportedly paying only $5 a month in 1963.

A real “mill hill” existed — one sloping down to the Henry River from the mill complex above. This is where the children of mill workers went sledding in the winter and served as inspiration for one of Peeler’s many poems.

Economic pressures from overseas competitors spelled the doom of smaller textile mills such as this, and the plant closed in the mid-1960s.

A fire destroyed the main building in 1977, not long after Sheppard had bought the whole site. Former residents have told Reyes, executive director of the preservation fund, that the last village residents didn’t move out until the late 1990s or early 2000s.

Today, the site has one employee and regular hours, five days a week. It provides unofficial “Hunger Games” fan tours and behind-the-scene private tours of the village.

What would have happened to Henry River Mill Village without “The Hunger Games” or without new ownership is difficult to say. The village already was decaying but still a place holding many memories.

“Everybody I talked to wanted to keep this place alive,” Young said. “It’s interesting to see how time changes places.”

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263 or mark.wineka@salisburypost.com.