David Shribman: When we worked together for a just cause

Published 6:09 pm Tuesday, July 3, 2018

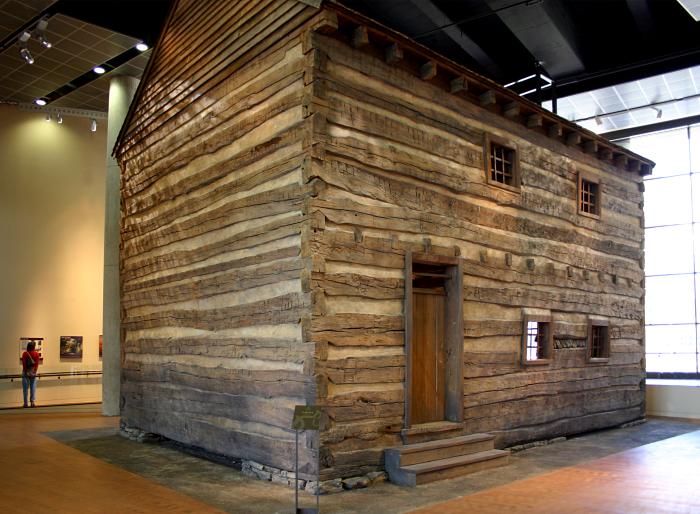

- The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center houses a 21-by-30-foot, two-story log slave pen built in 1830. By 2003, it was "the only known surviving rural slave jail," previously used to house slaves prior to their being shipped to auction.

CINCINNATI, Ohio — Lest we forget: The American Revolution was fought in the cause of freedom, but the battle for freedom did not end at Yorktown. And lest we think that the great monument to freedom is in Philadelphia, remember that another stands here on the banks of the mighty Ohio River, and it contains a message for us as we approach the birthday of the Declaration of Independence and its all-men-are-created-equal credo.

That monument, sitting only 175 feet from the onetime slave state of Kentucky, is the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, and its riverside position is symbolic of how close slavery and freedom were, and are. And it is a reminder, for our time and for all time, that the struggle for freedom never really ends.

The transit from slave-state Kentucky to free-state Ohio seems like a simple journey, just as the movement from rights-for-some to rights-for-all seems like a simple progression. In truth, neither was easy or simple, though today we consider both logical, if not inevitable.

Some of the 19th-century transit came with the Underground Railroad, which was never a railroad and not always underground, but a powerful movement and metaphor.

By geography and history, Cincinnati was a natural locus for the Underground Railroad. The city was pro-slavery in an anti-slavery state. The fastest growing city in the steamboat era, it sat on the primary water route to the slave markets of the South, even as it was a natural destination for runaway slaves. Blacks here were free, though not free from fear.

The Underground Railroad — the term perhaps first surfaced in 1839, when a slave said he hoped to ride to freedom on a railroad that “went underground all the way to Boston” — had a vocabulary (“conductors”) and a route map (sometimes bulkheads, sometimes trap doors, sometimes clandestine tunnels) all its own. The New York Times spoke of abolitionist societies owning “stock in the Underground Railroad, and (making) no bones of drumming up passengers for it.”

This metaphorical railroad moved by secret signals, whispery passwords, even directions derived from the position of the stars. The brave defiance of the prevailing culture and the law took place in root cellars and in wagons with false bottoms.

It was the precursor of the Great Migration of the 20th century, when descendants of slaves moved north in search of economic opportunity. And it required enormous daring. In his 1845 autobiography, Frederick Douglass spoke of being haunted by the notion that there was “at every ferry a guard, on every bridge a sentinel and in every wood a patrol or slave hunter.”

But the Underground Railroad may not have been the organized network portrayed in film and folklore. Instead, in the words of Eric Foner, the Columbia historian whose “Gateway to Freedom” is the most recent authoritative study, it was “an interlocking series of local networks, each of whose fortunes rose and fell over time, but which together helped a substantial number of fugitives reach safety in the free states and Canada.”

Even so, the obstacles to freedom — political, cultural and economic — were immense. Eleven of the first 15 presidents were slaveholders. The cotton trade, which sustained slavery in much of the South, was larger than the economic value of all other products of the United States economy combined.

The great words of freedom (“We hold these truths to be self-evident”) were written by a man who owned 600 slaves, 400 of them at Monticello.

That irony spurred another irony, that Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence — with a passage blaming King George for the problem of slavery excised before it was printed — was a fundamental impetus to the opposition to slavery. The anti-slavery leader William Lloyd Garrison cited that “self-evident” language in declaring “I cannot but regard oppression in every form — and most of all, that which turns a man into a thing — with indignation and abhorrence.”

One of the great wrongs of history, spawned by one of the great physical movements of history — by 1820 two-thirds of the North American population had roots in Africa — in turn spawned one of the great social movements of history.

“The abolitionist movement was the first great social movement in the world in terms of its objectives, its techniques and its results,” Marcus Rediker, the University of Pittsburgh historian whose 2007 book “The Slave Ship” is considered a landmark of historiography, said in an interview. “The struggle against the slave trade was tremendously important, a moment of great chutzpah.”

And it was an expression against the great chutzpah that was employed to support slavery, which Mississippi Sen. Albert Gallatin Brown once described as “a great moral, social and political blessing — a blessing to the master, and a blessing to the slave.”

Some of the conductors on the Underground Railroad were escaped slaves themselves, including Harriet Tubman, perhaps its best-known figure. Foner wrote of how William Thomson, who escaped Virginia, found refuge in a black church in New York. Another escapee, John Richardson, reached New York because of the efforts of a “colored man by the name of Jackson employed on one of the steamers.”

For that reason, much of the massive structure on the riverbank here is a tribute to the courage of enslaved people who yearned to be free and those who were determined to transform the yearning of other humans into human dignity. They include such forgotten American heroes as Levi Coffin, known as the “president” of the Underground Railroad; he and his wife, Catherine, may have sheltered as many as 2,000 runaways.

Today, the Underground Railroad serves as a reminder of the unrequited promise of our national narrative and an exhortation to continue the effort to extend freedom beyond its onetime boundaries. It is also an inspiration for our time.

“At a time of renewed national attention to the history of slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction, subjects that remain in many ways contentious,” Foner wrote in his 2015 account, “the Underground Railroad represents a moment in our history when black and white Americans worked together in a just cause.” That can happen again, if only we will it, and not only on Independence Day.

David M. Shribman is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (dshribman@post-gazette.com, 412 263-1890). Follow him on Twitter at ShribmanPG.