The author of ‘Frankenstein’ comes ALIVE!

Published 12:00 am Sunday, June 10, 2018

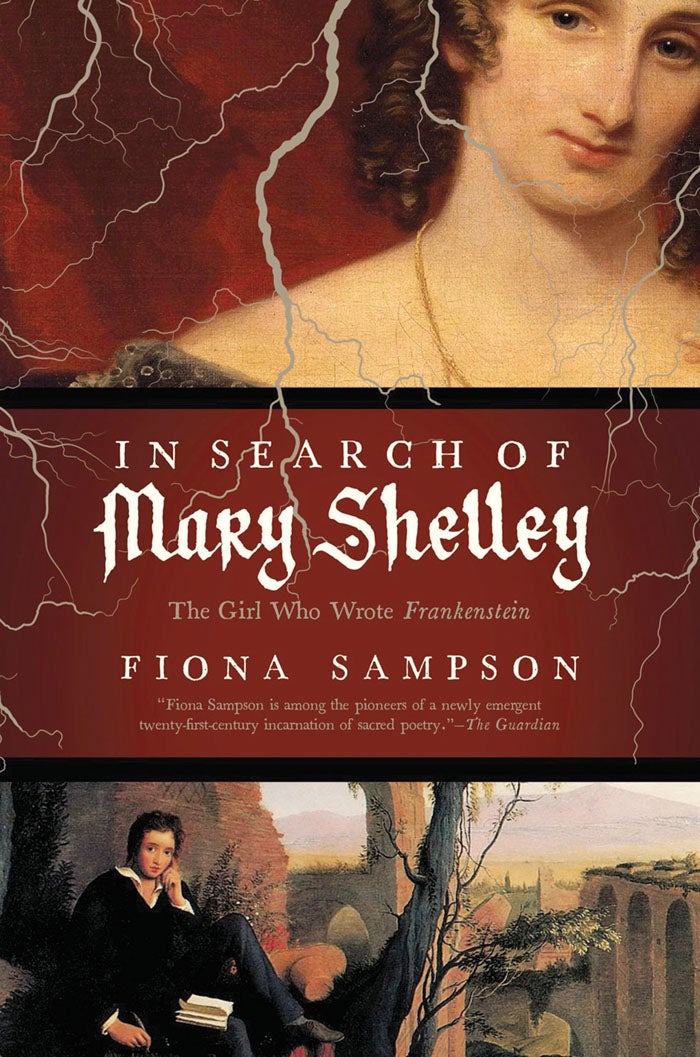

- In Search of Mary Shelley: The Girl Who Wrote Frankenstein

“In Search of Mary Shelley: The Girl Who Wrote Frankenstein,” By Fiona Sampson. Pegasus. 368 pp. $28.95.

By Charlotte Gordon, special to The Washington Post

Even for those of us who thought we knew everything about the young author of “Frankenstein,” Fiona Sampson’s brilliant new biography, “In Search of Mary Shelley,” has many surprises in store.

Not because Sampson has found a new archive of letters or dug up a trove of secret diaries, but simply because she has changed the angle of her lens, reimagining Shelley’s life so that suddenly new images loom and old truisms fade.

The historical Mary Shelley is still here (1797-1851), along with all the remarkable incidents and associations, including her relationship with Percy Shelley, her friendship with Lord Byron and her creation of that most famous gothic tale 200 years ago.

But the ground on which she stands, the very apartments in which she lived, are freshly illuminated, newly imagined, helping us draw closer to this fascinating but elusive writer.

All biographers know that Mary Shelley grew up at No. 29, the Polygon, a development north of central London, near today’s St. Pancras Station.

Many have tried to re-create the Polygon, which is no longer standing, by describing the contours of the buildings and the calls of the vendors who hawked their wares in the streets.

Others have used the architect’s plans to describe the mantels, the wrought iron balconies, the high ceilings and polished floors.

But Sampson, a poet and scholar at the University of Roehampton in London, does one better — something so simple and yet so astonishing that it sums up the magic of this book: She imagines the light streaming through the Polygon’s windows, illuminating Shelley’s childhood.

“The Polygon has tall, modern windows,” she writes. “Sunlight reaches right into the rooms. As yet there are no buildings close by to interrupt its progress across their polished floors, and the people who live here can always tell roughly what time of day it is. At the turn of the new century, letting light in has become more important than keeping out the cold: at least, for fashionable architects and their patrons. … There’s an aspect of display to the big windows of houses built, like this, in the Palladian style. Through their multiplying panes passers-by can see every detail of the rooms and the people who live in them. At times it’s almost as if the households of the Polygon are performing for the street.”

In Sampson’s skillful hands, the play of light becomes not only an evocation of life inside the house, but also an entry into the historical setting.

That the Polygon’s windows are large, Sampson points out, is evidence of modernity, especially when compared to the tiny-paned windows of the old houses in central London that “shut out more than the cold. They also exclude the outside world.”

These glimpses of early 19th-century London bring Shelley closer to the reader, particularly as Sampson frequently writes in the present tense. In fact, this is not simply a biography; it is, as the title tells us, a record of Sampson’s search for Shelley — a point she reminds us of by using questions like bread crumbs, steering us along the path of discovery. For instance, after re-creating the tragic death of Mary Shelley’s mother, the feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, 10 days after giving birth, Sampson pauses and wonders:

“What must it be like for a child to grow in the house where her mother has died, to pass the door of the death chamber on the landing every day? Perhaps Wollstonecraft’s daughters open it sometimes and step inside, looking around at the smallish, ordinary bedroom. Do they expect its banal bed and dressing table to communicate something? How can such big meaning be crammed into such a domestic space?”

Unanswerable though these questions are, they invite us to see the lamps and the stairs, the bedrooms and chairs, just as Shelley saw them — for a brief and exciting moment to inhabit Shelley’s body.

To drive this point home, Sampson addresses us directly, making us fellow travelers on the hunt for Shelley.

She quotes a passage from the journal of Mary’s young lover, the poet Percy Shelley, which describes the pair’s escape across the Channel from their enraged families: “Mary was ill as we travelled, yet in that illness what pleasure and security did we not share!”

Then Sampson remarks: “I’ve always wondered whether this passage is in code. … Mary has always been a poor traveller. … But she is also possibly in the earliest stages of pregnancy.”

Sampson arrives at this insight through the rigor of her scholarship and her imaginative process. In fact, if there is a lesson here, it is that the biographer must rely on both. It is not enough to supply us with a historical figure’s street address, the biographer must re-create the street, the house and the rooms of that house so that we can encounter a living being. This is not so different a project from Mary Shelley’s own: to breathe life into the dead, to bring new life to the archives of the past.

Gordon, a professor of humanities at Endicott College, is the author, most recently, of “Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley.”