Hard truths in ‘Swimming Between Worlds’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, May 20, 2018

“Swimming Between Worlds,” by Elaine Neil Orr. Berkley. 2018. 382 pp.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

It’s hard to decipher the takeaway from “Swimming Between Worlds,” a novel set in the late 50s and early 60s in Winston-Salem and Nigeria.

Its’ more than a little frightening to read about the race relations then — separate and not equal — and see where we are 60 years later, still separated, still not equal.

The novel raises fundamental questions. What is a white man’s role in fighting for basic rights for black people? Why does that desire to have others treated as you would be treated bring on so much hatred and violence? Why, after all these years, can we still not get along?

That’s just part of this book, though. It’s also about a smart young woman whose footings crumble when both her parents die. It’s about a young man with a good mind, a good heart and good intentions who repeatedly suffers for his convictions.

It’s about the changing landscape, culturally and literally, of a Southern city, and it’s about a woman being able to find her place in the world without relying on anyone else.

It’s a tough read. Kate, the young woman who finds herself alone in her family’s home in a nice Winston-Salem neighborhood, is truly lost. She has a serious boyfriend who’s in med school, but she’s not sure she wants that relationship anymore. She has no job, and no impetus to get one, since she can live off family money for a while. She’s directionless, purposeless, indecisive, disingenuous and coy. In other words, her dissembling can be irritating.

Then there’s Tacker Hart, former high school football hero, back in Winston-Salem licking his wounds after being dismissed from a plum architecture assignment in Nigeria. Author Elaine Neil Orr takes a long time to tell us what happened there and why. Many readers will assume the worst, but the truth — that he was too friendly with the natives — it’s almost an anticlimax, though still infuriating.

He and Kate knew each other in high school, but not well. He’s attracted to her precisely because she reveals little and keeps her most important thoughts to herself. Tacker admits he likes the mystery.

So, without a gold star for his work designing a school in Africa, Tacker decides he can manage his father’s grocery store. It keeps him away from the people who expected more from him.

But at that store, he meets Gaines, a black man — in this era, a Negro — who just wants to buy some milk for his little sister. But, blacks were not supposed to shop in white neighborhoods, or even walk through them. That was the sort of thing that got them beaten and arrested. Of course, Gaines is beaten when he walks out the store, and of course, Tacker comes to his defense.

So begins a relationship that requires sacrifice on both sides. But until the book’s end — a sucker punch of a resolution — the reader doesn’t really see how these three fit together, and how their little bits of life can cause so much damage.

Orr, who was raised in Winston-Salem and Nigeria, has a good feel for both. If you know Winston-Salem at all, you can follow her around the streets and out into the country and back again as Tacker and Kate search for their places.

And she knows Nigeria, which comes across as a bright place with great potential, at least in that era, where ambition is rewarded and friendship is important and hard work makes a real difference. She doesn’t mythologize the culture, but she makes it clear how different the two countries are.

She tells this complex story through Tacker and Kate, a third person narrator operating from both perspectives, but Gaines is only seen through other’s eyes. Orr never reveals his thoughts, except in what he speaks.

Was this Orr’s intention — to show how little the young white people really know about their black friend, his family, his culture, hopes and dreams? Kate never makes a decisive move to declare she is for civil rights. She’s scared. When she sees Gaines walk past her back yard, she’s scared. She worries what will happen to Tacker when he joins a sit-in at a lunch counter, or lets Gaines’ little sister stay at his house while Gaines is organizing protests.

Tacker, obviously, feels guilt over what he could not do in Nigeria, over the friendships he had to leave there, and about what his future will hold, what kind of man he will be.

Kate, meanwhile, has unearthed letters from her father, who drowned, to her mother. They completely change the way Kate feels about both her parents and raise frightening questions in her mind.

So the white heroes of this book are wrapped up in some sort of dilemma about where and how they’ve been and who and what they will be in the future. Gaines is sure, it seems. He will be a black man who can sit down to eat lunch. He will be able to walk into a white neighborhood without being arrested.

But when Tacker finally reconciles all the warring factions in his head, he’s faced with a decision. If he follows his dream, he’ll compromise his friend. If he doesn’t follow his dream, he loses his girl. Is he a sell-out, or just a man trying to understand a rapidly changing world?

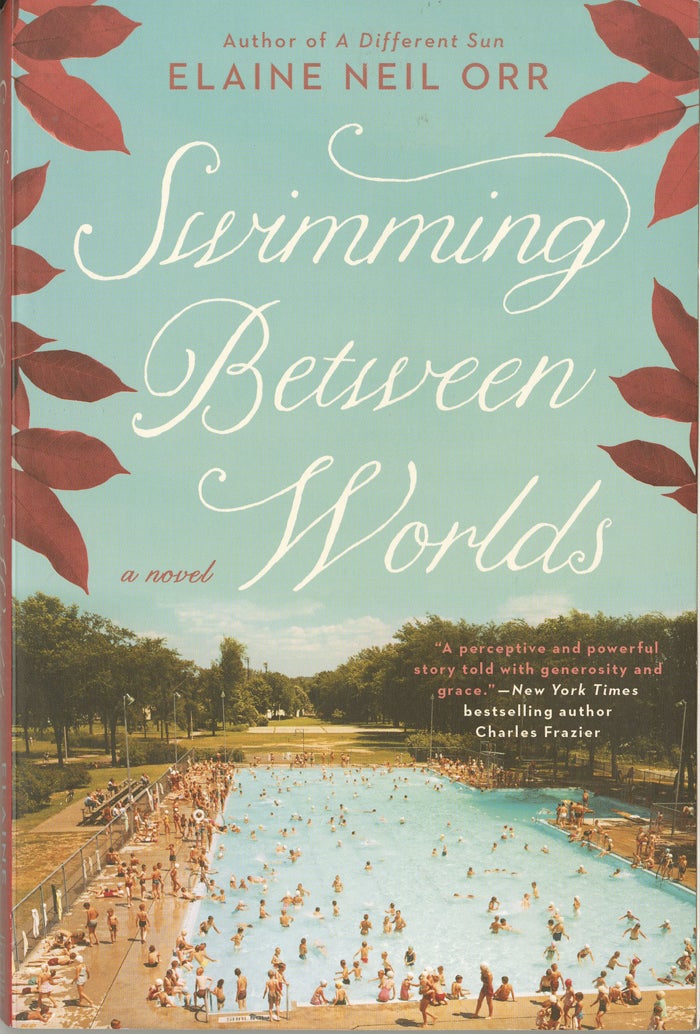

And this is where the swimming pool on the cover of the book plays its tragic part. Water is a theme throughout the novel, the Osun River in Nigeria, rain, gardens, pools, ponds. But this pool, in Hanes Park, will be the pivotal final point.

If Orr had ended the book there, it would have been a devastating lesson and an unforgettable one. She doesn’t. She scrapes up a little bit of hope, shows a little progress. We know how the world changed. The question is, where are we going now? And how will we respond?