NC-born NPR broadcaster Carl Kasell, who brought gravitas and goofiness to the airwaves, dies at 84

Published 6:36 pm Tuesday, April 17, 2018

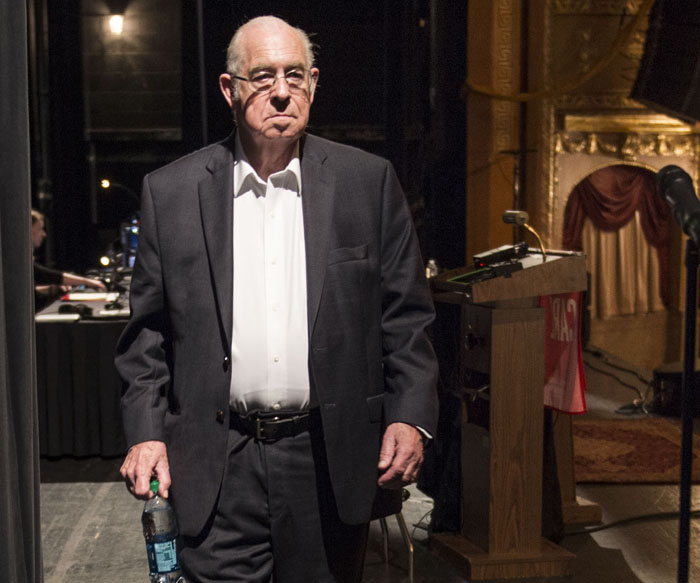

- NPR's News Broadcaster Carl Kasell wraps up a sound check for his final appearance on "Wait Wait . . . Don't Tell Me: Carl Kasell's Farewell Show," at the Warner Theater in Washington on May 15, 2014. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post photo by Nikki Kahn.

By Adam Bernstein

The Washington Post

Carl Kasell, a radio personality who brought gravitas and goofiness to the airwaves, first as a staid news reader on NPR’s “Morning Edition” and later as the comic foil and scorekeeper on the delightfully silly news quiz show “Wait Wait … Don’t Tell Me!,” died Tuesday at an assisted-living center in Potomac, Maryland.

He was 84.

The cause was complications from Alzheimer’s disease, said his wife, Mary Ann Foster.

Kasell’s voice, resonant, reassuring and with a lilting trace of his North Carolina tobacco country heritage, helped define NPR as an emerging force in news broadcasting. He joined the public radio network in 1975 and, four years later, helped inaugurate “Morning Edition,” writing and reading five-minute top-of-the-hour news updates from pre-dawn to the lunch hour.

For 30 years, he was an unflappable anchor of that digest, bringing a no-frills seriousness to unfolding history, from the 1979 Iranian hostage crisis to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

His skill was conveying the drama of the news while maintaining an unforced conversational delivery, what an NPR executive once described as the warm voice of an informed companion.

He parlayed that stolid reputation into unexpected laughs when he signed on for “Wait Wait” in 1998. He became the semi-straight man to host Peter Sagal, becoming public radio’s institutional voice in playful harmony with a Chicago-based actor, writer and all-around wiseacre who declared his intent to run a weekly show that boasted the motto “NPR without the dignity.”

Some NPR executives initially fretted that Kasell’s participation on a program that lampooned the news and public radio tropes would collide with the venerable anchor’s normally sedate on-air reputation. But as Sagal once told The Washington Post, “Deep inside that serious newscaster persona was a huge piece of cured North Carolina ham.”

(An amateur magician, Kasell once sawed NPR legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg in half.)

“Wait Wait” executive producer Doug Berman, known to credit-attuned listeners by his moniker, “The Subway Fugitive,” had been trying to cast the show when he heard Kasell field questions at a public radio conference. A woman asked what time Kasell woke to do his job. “1:05 a.m.” the newscaster replied. Someone bit. “Why 1:05?” “Because 1 is too damn early.”

The quip showcased the possibilities, in Berman’s view, of pairing Kasell as a dry-witted second banana to the first “Wait Wait” host, the short-lived Dan Coffey, and then to Sagal.

“I like to say they brought me into the show to add dignity,” Kasell deadpanned to the Wall Street Journal. “I’ve brought dignity, stability and class.”

In a recent interview for this obituary, Sagal called Kasell pivotal to the show’s fortunes, saying his credibility as the “voice of NPR, the brand as a voice, made us sound like we were an actual NPR show.” Sagal said that Kasell struggled earnestly to re-create celebrity voices on the show, including newsmakers such as Britney Spears and Monica Lewinsky, but he was not any good at it.

“He was in on the joke,” Sagal said. “You could laugh at him, and he’d love it.”

The show has become one of the network’s most popular and enduring staples, fetching millions of listeners on Saturday mornings. It features a panel of humorists and journalists vying on behalf of listeners for Kasell’s voice to be played on their outgoing voice-mail message — “a prize that’s invaluable and worthless at the same time,” Berman told the Wall Street Journal.

One of the recurring games, “Who’s Carl This Time?,” featured Kasell impersonating newsmakers as varied as O.J. Simpson, President George W. Bush and Keith Richards. For a quiz called the “Listener Limerick Challenge,” he read doggerel that tested call-in contestants on their knowledge of the week’s news. For “Not My Job,” he prodded guests such as writer Salman Rushdie to answer questions distinctly outside their area of expertise — in his case, Pez dispensers.

At various times, he was called on to warble less-than-definitive covers of Tom Jones’ “What’s New, Pussycat?” Peggy Lee’s “Fever” and the “Macarena.”

“I’m not a mimic,” he told the Chicago Tribune, saying he was merely following a tradition set by George Fenneman, Groucho Marx’s sidekick on the radio and 1950s TV quiz show “You Bet Your Life.” “I try my best and sometimes, oftentimes, it fails. But I’m told there’s a certain charm about it that people like.”

Carl Ray Kasell (pronounced “castle”) was born in Goldsboro, North Carolina, on April 2, 1934, and was one of four children. His father, he once told a reporter, “was a guy who kind of bounced from job to job,” with little money to show for it.

Radio, with comedians such as Jack Benny and serials such as “The Lone Ranger,” became his source of entertainment and escape. As a child, he hosted a “music show” on his grandmother’s windup Victrola — reciting fake commercials between the 78s — and also played practical jokes using the family radio.

“Before I even started to school,” he told NPR, “I sometimes would hide behind the radio, which would be sitting on a table, and pretend that I was on the air and try to fool people who came by to listen.”

He won many lead roles in high school drama productions. Future TV star Andy Griffith, who had moved back to North Carolina to teach and hone his nightclub act, once played Sir Walter Raleigh to Kasell’s Indian chief in a summer stage production and encouraged the young man to pursue a career in theater.

“I told him, ‘No, I’m going to be a radio star,’ ” Kasell told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Kasell studied English and helped start a radio station with fellow student Charles Kuralt, who became a CBS newsman celebrated for his folksy “On the Road” segments.

Kasell, in the Class of 1956, left the university shortly before graduation to fulfill Army service. After his discharge, he jobbed around as a disc jockey and newscaster at commercial stations in North Carolina and Virginia, including WAVA-FM in Northern Virginia, before joining NPR.

His “Morning Edition” schedule was not necessarily conducive to family life, but he stole hours of sleep in the afternoon before watching his son’s Little League practice and then returned to bed in time to wake at 1 — or 1:05.

His first wife, the former Clara de Zorzi, died in 1997 after 37 years of marriage. In 2003, he married Mary Ann Foster.

Besides his wife, of Washington, survivors include a son from his first marriage, Joe Kasell of Ashburn, Virginia; a stepson, Brian Foster of Washington; a sister; and four grandchildren.

Kasell, a longtime announcer for the annual Kennedy Center Honors broadcast on CBS, was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2010 and spent many years as NPR’s “roving ambassador.” He inspired merchandise — a Carl Kasell plush toy doll, in the form of an old man wearing a suit and holding a radio microphone. He stepped down from “Wait Wait” in 2014, sparking tributes from President Barack Obama (“Barack, from Washington, D.C.”), actor Tom Hanks and comedian Stephen Colbert, among others.

Bill Kurtis, the announcer and news anchor known for his stentorian voice, succeeded Kasell, who that same year published a memoir, “Wait Wait … I’m Not Done Yet!”

Kasell estimated that on “Wait Wait” he put his voice on more than 2,000 answering machines. He was game for all kinds of requests, up to a point. He once declined an offer that he felt sounded too much like an advertisement for a business. But he was open to singing “Oklahoma!” the disco hit “I’m Your Boogie Man” and the Meow Mix cat food jingle.

He also custom-tailored limericks if winners preferred his poetry to his balladry.

On his home machine, it was his wife’s voice greeting callers. “I’m a psychotherapist,” she said recently, “and I would have loved to have had his voice, but I didn’t want to get too cute.”