My Turn, Ray Moose: Freedom for guns & art — consider the whole truth

Published 7:28 pm Tuesday, March 20, 2018

History is a parent of culture. It serves as a map into the past and can answer questions about the foundation of a culture. It can also help piece together answers to questions that arise in the present.

In this postmodern climate, there is the tendency to cover up history. This is not to our benefit. A look back into history can serve as a guide into the future.

The current issue on the table is the gun debate. A worthwhile place to start is the Second Amendment and how it came to such a prominent position in our Bill of Rights.

Colonial America was a wild place. Food for many was available only through farming and hunting, so in many cases the gun was the only thing standing between survival and starvation for many families, especially in the years that crops did not do well. Also, a gun hanging loaded on the wall was the law enforcement of the time for many.

With the coming of the war of independence in the late 18th century, the commander of the colonial army, George Washington, struggled with an insufficient number of guns. This issue elevated the status of guns to a level of importance that was only surpassed by driving the British into the sea and making us one of the few countries in the world that exists because of guns.

This importance of guns was passed down generation to generation and carries much weight even to this day.

The question is, how were millions of lethal guns in America, from its beginning in the late 18th century, with no campus shootings until 1966 on the campus of Texas A&M University? That is 200 years. What exactly is different about our culture in pre-1966 and now? Actually, many things are different.

The changes in these last years have been more accelerated and far-reaching than any generation before us, and a perfect storm of societal and technological changes has fragmented and torn the social fabric. Are these shootings the dead canary in the coal mine? If so, what is the cause and what are the symptoms?

The big tear in our fabric began in the 1960s with the Vietnam War and has spread through the culture with many different faces and causes — but always with disagreement, mistrust and anger, and always the same people and political parties facing off.

Just before Columbine in 1999, America still had a strong manufacturing base. The children that fell through the cracks could go to work at a textile or steel mill or auto plant or machine shop, plus a thousand more possibilities. Maybe not an ideal life, but a life nonetheless. A move that has benefited our financial barons and those invested in them. Some may say that unemployment is only 4 or 5 percent. Sorry, it’s not the same; we are in a service-based economy now with very big changes in a short amount of time.

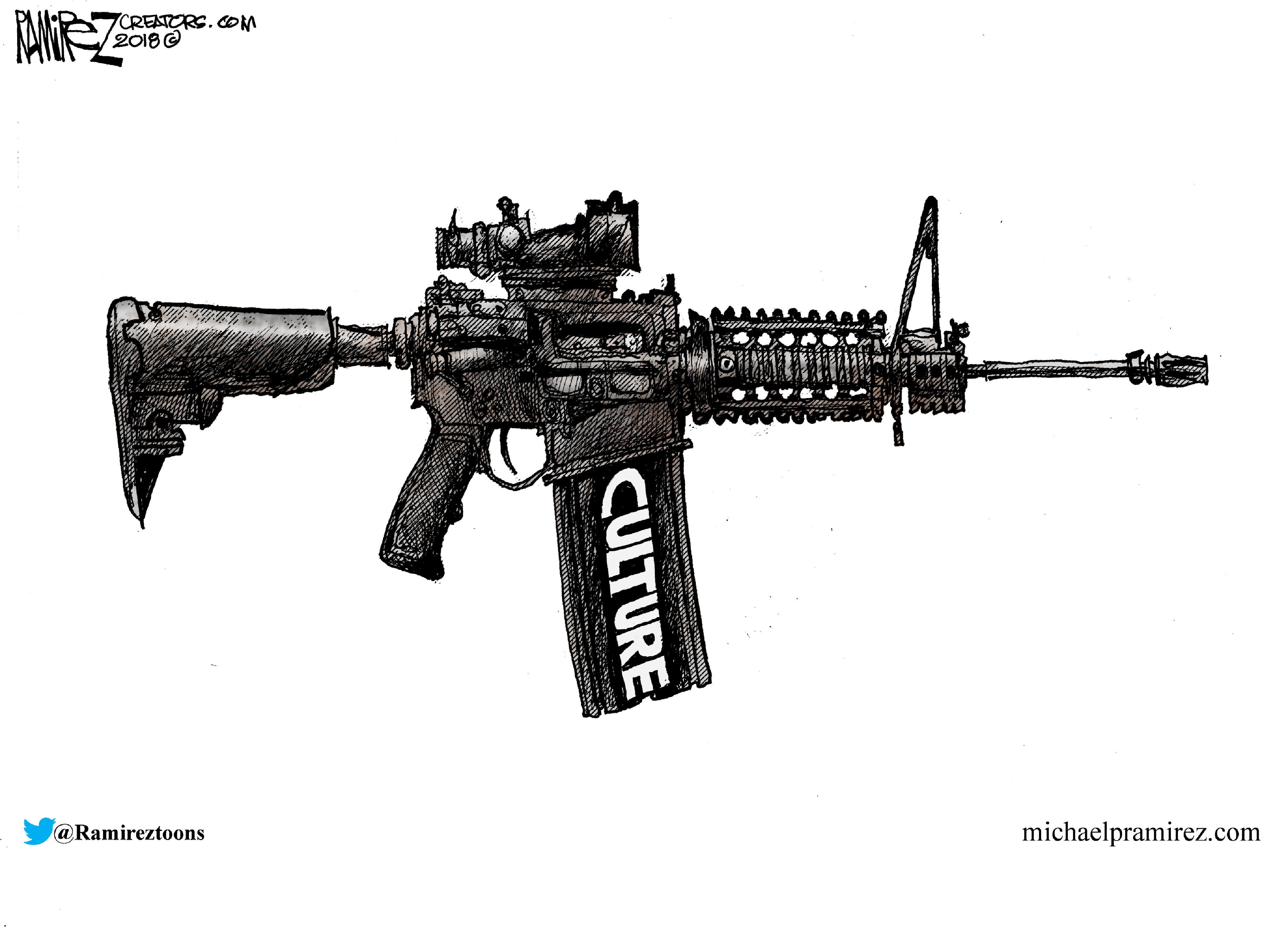

Beginning in the ’60s and accelerating into the ’90s and beyond, television, movies and most especially video games put the violent American archetype on the screen. The hero kills the villain and all is resolved. The idea of some being desensitized to human life is not far-fetched. Some say there is no statistical evidence of that. Maybe not, but empirical evidence points out a parallel and a connection between the advancement of these arts to the acceleration of aggression.

A breakdown in morals and respect for others, disintegration of the family, a lack of basic manners and social awareness and disregard for history have followed us into postmodern America. Are we trying to treat the symptom instead of the cause by putting all the emphasis on guns?

Guns are too easy to obtain. Some guns and ammo should not be available at all, and all legal gun owners should accept this for the benefit of gun ownership itself.

Some sacrifices need to be made for the good of the whole, but let us not forget that we are addressing the Second Amendment here and its direct connection to the First, which includes the free speech of the arts.

It is incumbent upon any gun culture to be respectful of itself or the consequences may outweigh the intent, and the same applies to the arts. Every culture should respect the power of art on the human subconscious mind, even a culture that discounts it.

Throughout human history, it has been the role of the artist to elevate. A good example of this in our time is Ken Burns’ documentary on Vietnam, in which he had the depth, empathy and insight to see the soul of both sides of the issue and put forth the “whole truth,” which can only happen when the artist is willing to sacrifice short term monetary windfall and take an overview that sees the entire picture.

Artist Ray Moose lives in Mount Pleasant.