Rebecca Rider: An apple a day

Published 12:00 am Thursday, March 15, 2018

It doesn’t take long for the legends of pioneer days to fade from memory. I can’t think of a child who doesn’t love stories about Paul Bunyan, Davie Crockett, Pecos Bill or John Henry. But bring those names up to adults, and the details grow hazy.

“Which one was that, now?” they might ask.

They’ll confuse Davey Crockett and Daniel Boone, or forget that Bunyan’s ox was blue or that Pecos Bill could turn his horse on a dime. And few remember which tales were true or which were tall. Any knowledge of the man behind the myth is often consigned to the margins of high school history books, forgotten as soon as the covers close.

But people in some places remember. Travel west to Fort Wayne, Indiana — a small city hemmed by fields and pasture — and you’ll find reminders of pioneer Johnny Appleseed everywhere: on signs, street corners, parks, mascots and sports teams.

While most other places have written the tin-capped gardener off as storybook fantasy, Fort Wayne remembers the truth.

On a recent visit to the Midwest, a friend asked me if I wanted to see the place where Johnny Appleseed was buried.

“You mean he’s real?” I asked.

I, too, had forgotten.

Appleseed’s grave is not where you’d expect it to be. It’s not in a park or an orchard or even in a grove. It’s on the flat section of a greenway, perched between the slopes of two steep, artificial hills. Below is a parking lot and a set of small baseball fields. The hill above marks the start of the grounds for a massive coliseum — the concrete and glass of it dominates the horizon.

But there’s still some quiet to be found. The grave is protected by hedges and an iron fence, and a few spindly trees shield it from a busy road.

For outsiders like myself, there’s also some handy informational boards nearby.

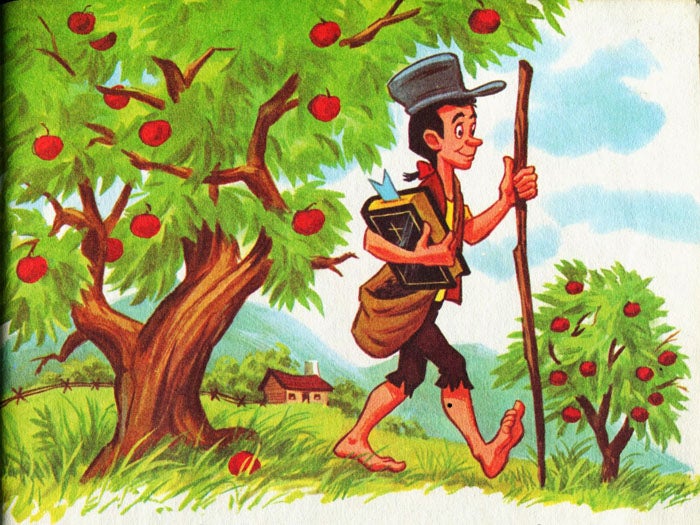

As it turns out, Appleseed is not, as tall tales would have us believe, the barefoot, eccentric naturalist who dropped apple seeds as he walked — or, at least, not completely.

Born in the 1700s as John Chapman, he was a clever, successful businessman who helped soften the rough edges of the frontier with nurseries and orchards.

Chapman would travel ahead of pioneers through Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, purchasing land and planting orchards or starting nurseries full of apple trees. As settlers trickled West, Chapman would sell the land and the saplings for a profit, even charging extra to plant the trees himself.

But the stories weren’t all wrong. Chapman did tend to walk barefoot and to wear a tin pot in place of a hat. He was also a missionary and came to be known for his generosity.

The epitaph on his tombstone is right above a rough illustration of the Bible, and says, “He lived for others.” So maybe the tales are true, after all.

His story has grown, spread and flourished, just like the apple orchards he once planted — orchards that his legend now outlives. And no matter what time of year you visit, there’s always an apple or two resting at the foot of his grave — tributes, perhaps, from fellow travelers who are still looking for a softer world.