Make this flu epidemic a cure for complacency

Published 6:19 pm Tuesday, January 30, 2018

Bloomberg View

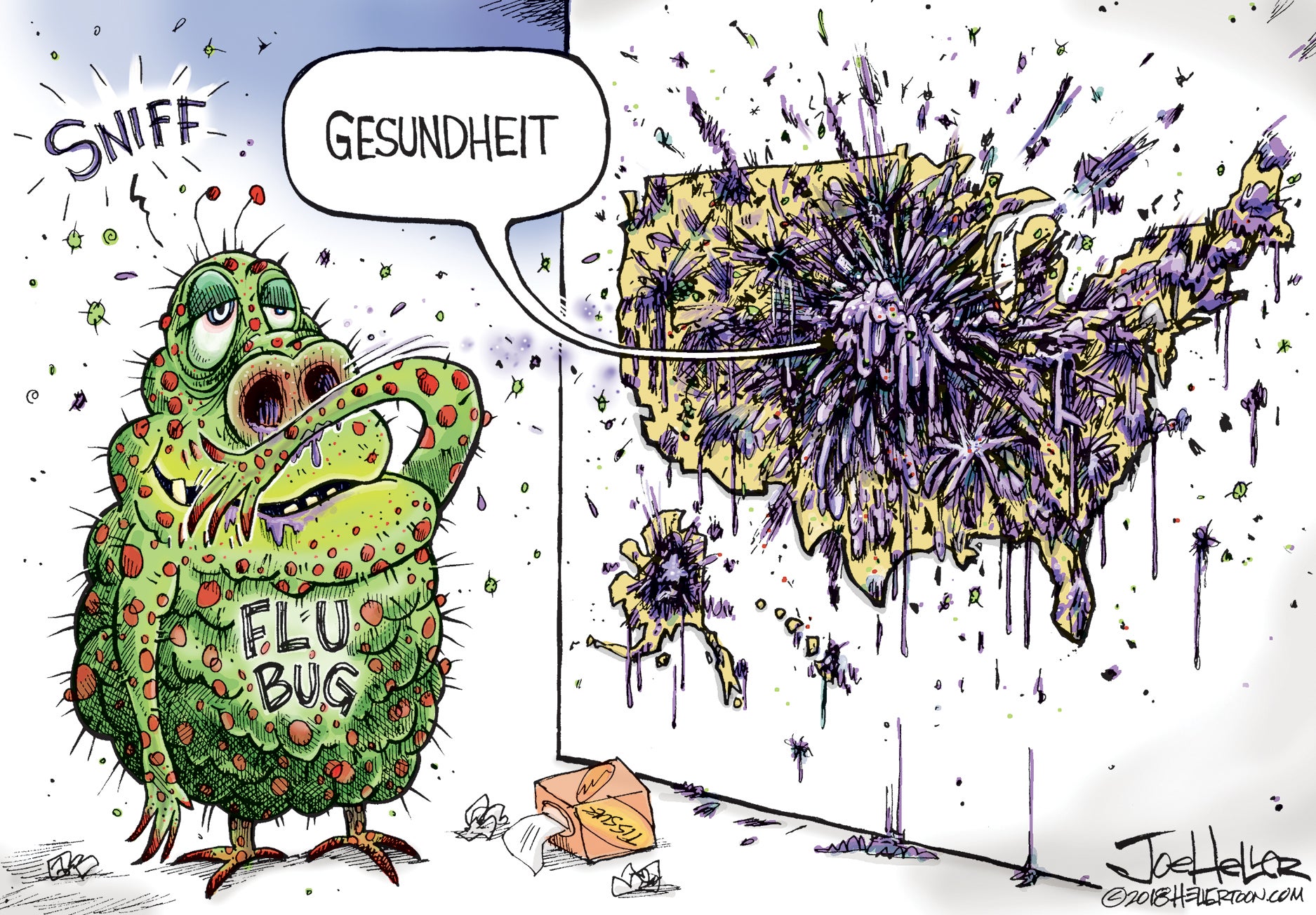

This year’s flu epidemic arrived early, spread widely and brought extraordinary suffering expected to continue for months. The question is whether it will be enough to jolt the medical world and its funders from their complacency about influenza’s persistent power.

Much more investment is needed to get hospitals better prepared for future outbreaks, and to improve seasonal flu shots and treatments. Also lacking is a lasting, universal vaccine.

Researchers have been working on such a vaccine for years — one that could induce immunity to parts of the flu virus that don’t vary among strains or change over time. They’ve developed promising strategies, but they need more funding to speed the work along. This year, the U.S. government is devoting just $32 million to the effort.

At the same time, more should be done to address the annual flu threat. Viruses like H3N2, the one causing all the trouble this year, are bad enough. But things will get far worse when a new virus arises to which almost no one is immune. Such viruses cause pandemics like the Spanish flu of 1918 and the Hong Kong flu of 1968-69.

The next time this happens, there’s a real danger that hospitals and public-health programs will not be ready. In recent years, their budgets have fallen by about a third. The next big flu could leave them short of beds, ventilators and other equipment. This year, many are straining to accommodate the flood of patients.

Researchers also need to improve the process for creating annual flu shots, which normally takes six to nine months. That’s time enough for the target viruses to become resistant. Moreover, the way the vaccines are usually grown, in chicken eggs, can lead to mutations that render them less effective. That’s what happened with this year’s vaccine.

Vaccines produced in mammalian cells could get around this problem, though the method is currently more expensive and takes just as long. Vaccine makers are still testing other strategies to make effective flu shots faster.

Better efforts are also needed to raise the vaccination rate in the U.S. above 50 percent. New tools are required for diagnosing flu, and doctors need treatments without punishing side effects.

H3N2 is an uncommonly fierce virus, especially for people born before 1968, whose crucial first exposure was to a different strain. With luck, the misery it’s bringing will deliver a sufficiently strong warning. If more isn’t done, the next big flu could be much worse.