Sports Obituary: Colonel Bob Waggoner, former Boyden and Wake Forest star

Published 12:00 am Friday, December 1, 2017

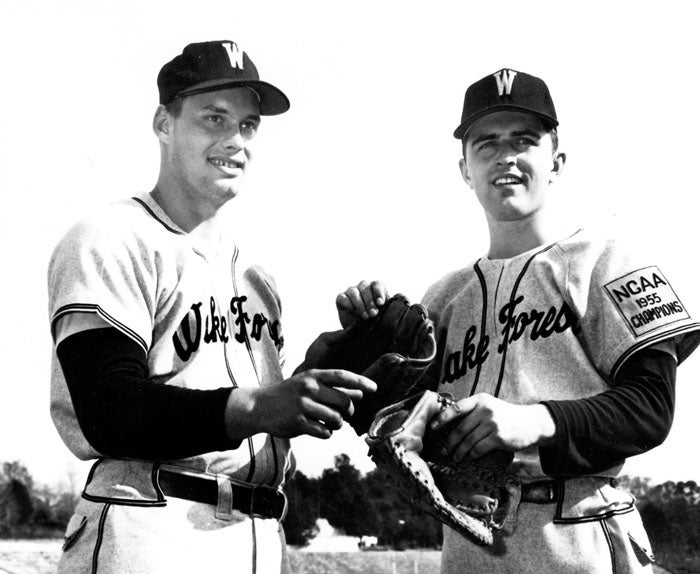

- Frank McRae, left, and Bob Waggoner, right, of Salisbury and Boyden High School, were key members of the 1955 Wake Forest baseball national championship team.

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

CHARLOTTE — Colonel Bob Waggoner, a local athlete who was one of the heroes of Wake Forest’s 1955 baseball national championship, died on Thanksgiving Day. He was 83.

We had a number of conversations over the years. He’d call and say he was making a visit to Salisbury, his hometown, and then he’d drive me and one or two of his old teammates to a restaurant. His favorite meal was barbecue at Richard’s. Twice, when I scrambled into the back seat of Waggoner’s vehicle, legendary coach Joe Ferebee was a passenger in the front seat. Those were priceless lunches. I listened to history. Waggoner always went out of his way to make me feel like part of the gang. Then he’d pick up the tab.

Waggoner was a modest man. He’s not in the Salisbury-Rowan Sports Hall of Fame and never asked why. The only time I saw him get excited about the local Hall of Fame was when his buddy Frank McRae was being inducted in 2008. Waggoner was certain McRae, All-State in basketball and baseball in his days at Boyden High, was one of the best athletes ever to come out of Rowan County. When McRae died without any public announcement in 2016, it was Waggoner who called the Post to let us know. That was the only time he ever asked for anything. He asked me to write a story about his friend.

Waggoner and McRae went way back. They were teammates on Ferebee-coached Boyden High and Salisbury American Legion teams before they were reunited to make history at Wake Forest.

For the 1951 Salisbury Legion team, Waggoner usually batted third, with McRae, a feared slugger who launched 24 homers between high school and Legion, hitting cleanup. Waggoner was a southpaw and was in the pitching rotation, along with the right-handed McRae. If Waggoner didn’t pitch, he played first base or left field. Waggoner scored 25 runs in a 27-game season, mostly because McRae was hitting behind him. Players were younger then. Games were lower-scoring with wood bats. Every run was important.

Waggoner experienced considerable success on the mound. He beat Concord twice in the summer of 1951, once with a shutout. Hurlers frequently pitched complete, nine-inning games then. In his strongest effort, Waggoner won, 7-2, against Albemarle, going the distance, striking out 15 and allowing no earned runs.

As a Boyden senior in 1952, Waggoner and McRae handled the bulk of the pitching duties for a second-place team. They were always the No. 3 and No. 4 hitters in Ferebee’s lineup. Waggoner played first base when he didn’t pitch. McRae roamed center field.

Waggoner pitched a two-hitter — those were nine-inning high school games then — and still lost to the Greensboro High Whirlies. He struck out 11 batters in relief against Gastonia.

In their final high school game against High Point, McRae walloped a long homer and was the pitching star while Waggoner tripled and knocked in three runs. They pulled off a double steal, with McRae drawing a throw to second, as Waggoner dashed home. Waggoner would make a more famous slide into home plate in Omaha, Nebraska, three years later.

Waggoner was invited for a tryout by the Cincinnati Reds after graduation, traveled up to old Crosley Field, smacked a few home runs for the scouts, and got to meet met several of the New York Giants, including Bobby Thomson and Whitey Lockman. They were in town to play the Reds. Waggoner also got a look at Cincinnati first baseman Ted Kluszewski, 230 pounds of muscle, and realized his chances of making it to the majors were slim.

Waggoner was playing for a mill team in Cooleemee when Wake Forest baseball coach Taylor Sanford spotted him. Waggoner hadn’t been more than an average high school student, but baseball gave him an opportunity to get into Wake Forest. He made the most of it. He got involved in the ROTC program, a decision that would lead to a career in military service. He also carved out a starting role on the baseball team. Wake Forest had better hurlers than Waggoner, but he was a pretty fair hitter and he excelled at first base defensively.

The Deacons were strong in 1955 when Waggoner was a junior, and they made a run. The ACC was young then. Wake Forest ruled the league with three Rowan products in the starting lineup. McRae had gotten stuck behind superstar Dickie Hemric on Wake basketball’s team, but he shined in left field in baseball. Billy Barnes, the third baseman for the Deacons, was from Landis. He was Wake Forest’s best football player, but he was as good in baseball as football. If not for concerns about his eyesight, Barnes may have ended up in MLB, instead of the NFL. He actually loved baseball more.

In 1955, Wake Forest was a conservative Baptist school with just 1,200 undergraduate students, but after the Deacons took care of Rollins and West Virginia in the District 3 tournament, Waggoner and his teammates found themselves on an airplane bound for Omaha’s Rosenblatt Stadium, the site of the College World Series. It was the first plane ride for some of them.

Wake Forest played six games in that World Series and only had ace pitcher Lefty Davis available for one. Davis was in summer school, but he made it to Nebraska to pitch a weekend shutout. Wake also played without captain and right fielder Tommy Cole the last three games. Cole injured an ankle in a 9-0 loss to Western Michigan. That loss placed Wake Forest on the ropes in the double-elimination tournament, but the Deacons came back to win their last three games, including 10-7 and 7-6 victories against Western Michigan.

Waggoner was a difference-maker in Wake Forest’s opening game on June 10 against Colgate.

The Deacons had been told to expect 100-degree temperatures in Omaha. What they got was bone-chilling rain and a hailstorm unlike anything they’d ever seen. It was 0-0 in the fifth inning when ugly weather suspended play for 78 minutes. Barnes crouched like a tiger on the dugout steps, while Waggoner tried to relax. Sand was dumped on the field, and play resumed. Both starting pitchers were in control . Both were determined to finish what they’d started.

With the game still 0-0 in the eighth, Waggoner walked on a 3-and-2 pitch to start the inning. Pitcher Jack McGinley laid down the sacrifice bunt that advanced Waggoner to second. As he inched off second base, observing the perilous field conditions and the treacherous footing he would experience if he had a chance to gingerly round third base, Waggoner nevertheless knew he had to try to score on any base hit to the outfield.

With two men out, Luther McKinley dumped a hit over second base, just Wake Forest’s second hit of the game, and Waggoner never hesitated. Colgate’s center fielder was playing shallow. His throw home arrived before Waggoner. But Waggoner kicked the ball out of the catcher’s mitt on his slide. Art Gore, a National League umpire, spotted the ball on the ground and made the safe call. Wake would win, 1-0.

Wake went on from there. In the final game of the World Series on June 16, the 7-6 win against Western Michigan, McRae would go 5-for-5 at the plate and made a diving catch in left field. The final out was a groundball fielded by Barnes. He fired the ball across the diamond to first base. Waggoner squeezed it, and Wake Forest won the national championship.

That team would become important and historic because the ACC wouldn’t produce another baseball national champion for 60 seasons. When Virginia finally broke that mind-boggling ACC drought by winning it all in 2015, I put in a call to Waggoner to get his reaction. I thought he might be upset. After all, his team’s claim to fame hinged largely on its unique status in the history of ACC baseball.

But he was anything but upset. He was thrilled. That said a lot about him.

“Virginia is one of the old-timey ACC teams,” Waggoner said that night. “That was important for me — and really important for my wife. We were glad to see Virginia win. What I like best about Virginia winning is they came out of nowhere with no one expecting it. Sixty years ago, we did the same thing, and 60 years is way out of the ordinary. Virginia winning doesn’t take away from what we did. We’ll always be the first ACC team to win a national championship and the first North Carolina team.”

Waggoner, McRae and Barnes were among the honorees when Wake Forest recognized the 1955 champs in ceremonies prior to a game against N.C. State during the 2015 baseball season. All the team members in attendance received a polished black bat commemorating their accomplishment.

The best year of Waggoner’s life always was 1955. He got married in December of that year to Ann Scruggs, his college sweetheart.

Not long after the championship parade that welcomed the victorious Deacons home from Omaha, Waggoner was sweating in Georgia, at Fort Benning, six weeks of basic training as part of the General Military Science Reserve Officers Training Corps. He dealt with rattlesnakes, lightning strikes and scary sergeants.

Some of the magic was gone, but he played his senior baseball season for Wake Forest in 1956. McRae’s shoulder was hurt, so they switched positions, with Waggoner shifting to left field and McRae taking over first base.

Waggoner was commissioned as an officer later in 1956. He studied artillery and guided missiles at Fort Bliss in Texas. He would serve in the United States Army Field Artillery for 30 years. Among other stops, he had two tours in Germany and he served in the Vietnam War.

Waggoner is survived by his wife and three children.

He’ll be buried in Arlington National Cemetery.