Remnants of Confederate Prison barracks located

Published 12:13 am Thursday, August 31, 2017

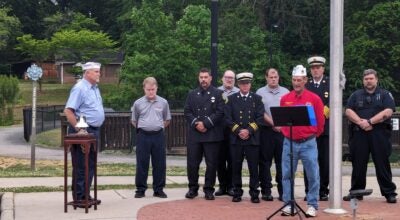

- Ari Lukas (left) answers a question by Steve Cobb about the findings of the ground penetrating radar on the plot of land on East Bank street. Lukas, along with Dr. Roy Stine and Megan Cope, gave a report of the findings of the radar survey of an empty lot on East Bank Street in Salisbury that has been long thought to be where some of the structures of the historic Salisbury Confederate prison were located. Jon C. Lakey/Salisbury Post

SALISBURY — Archaeologists will go to work in the coming months to unearth remnants of a Confederate prison building that once stood off East Bank Street.

Ground-penetrating radar has located signs of a portico or doorway into the main building on the prison grounds, archaeologist Ari D. Lukas told a group gathered Tuesday at the Salisbury Station to hear his findings.

“We’ve got the barracks,” said Susan Sides, president of Historic Salisbury Foundation. She said the news gave her cold chills.

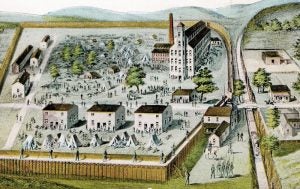

The finding was the result of geophysical investigations of a lot at 313 E. Bank St., given to Historic Salisbury Foundation by Jim and Gerry Hurley. The vacant lot, which is between two houses, was the site of at least part of a former cotton mill that the Confederacy filled with prisoners of war in 1861-65.

To locate any possible remnants of the prison, Historic Salisbury Foundation sought the help of experts from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. A team from the Remote Sensing Laboratory in the geography department visited the site twice in 2016, on Oct. 30 and Nov. 12, and gave its report Tuesday. The team was led by Roy S. Stine, with Lukas acting as project field director.

Using ground-penetrating radar equipment that could go as deep as 8 feet, they surveyed 888 square meters at 313 E. Bank St. and a lot across the street. Lukas said the footprint of the building, as seen from the shape file produced by the survey, as well as historical paintings, helped locate what appears to have been a doorway or portico near the back of the lot. The doorway extended from around the middle of the cotton mill’s north-facing wall.

“We’re super excited about it,” Lukas said.

The foundation of the building — or at least the section that supported the northern wall — may still be in place. The survey found signs of such construction 25 to 34 centimeters below the surface.

Lukas and others who worked on the project recommended that the foundation bring archaeologists back to see what they can literally uncover.

There seemed little doubt Tuesday that such work will take place soon. Megan Peters, a graduate student who has worked on the project, will likely take on the excavation as part of her studies. Timing will depend on her schedule and available resources.

Peters would not be the first to excavate land in the area; another team did similar work in the summer of 1983 and 1984. But Peters will have a more precise idea of where to start.

The report was another step in Historic Salisbury Foundation’s effort to find evidence of a prison buried long ago — and for good reason. The prison became severely overcrowded as the Civil War progressed, and thousands of Union soldiers died of disease and starvation there. Many are buried in trenches at what later became the National Cemetery off Military Avenue.

A new prisoner exchange program in February 1865 led to the transfer of the remaining prisoners. Union Gen. George Stoneman arrived in April and ordered the prison burned.

The property was eventually leveled as houses were built in the area. The house that sat at 313 E. Fisher St. burned down in the 1990s.

Steve Cobb, vice president of Historic Salisbury Foundation, asked if the site could be excavated to the point that the public could come and see the remains of the prison barracks. That depends on what the team finds, said Linda Stine. “There are lots of maybes.”

A replica of the building and a sign explaining the structure’s significance might work, she said.

Aaron Kepley, director of the Rowan Museum, said he has encountered descendants of men who were held at the prison and want to see where it was.

Anne Lyles, who lives in the area, said the people in the neighborhood have discussed the prison that used to sit nearby. “We think it should be commemorated.”

Susan Kluttz, former N.C. secretary of cultural resources, was present for the presentation and said she loves having experts come in from around the state to examine the site. “It’s very exciting, as important as history is to Salisbury,” she said.

Ed Clement, the father of historic preservation in Salisbury, was eager to see the project go forward.

“It brings emphasis to an important site that in some respects we have overlooked, but in other respects we have looked forward to the day when we can begin an education process for the people of Rowan County and really beyond,” Clement said. “I see it as a first step.”

He said mention of the suffering that went on behind the prison stockade made his mother tear up. “Her mother and father threw food over the fence to starving prisoners. She’d heard about it all her life.”