Buried in ‘Shadow Land,’ a story of undeserved suffering

Published 12:00 am Sunday, April 30, 2017

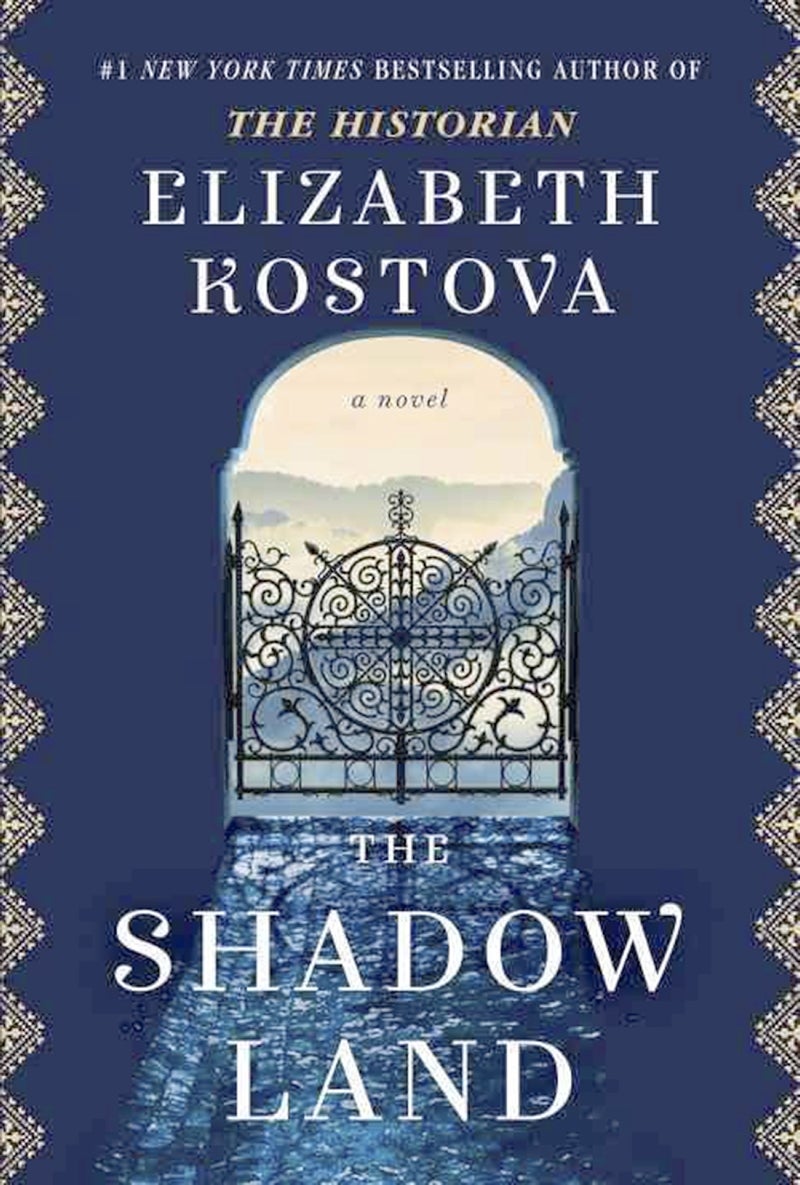

The Shadow Land, by Elizabeth Kostova. Random House. 496 pp.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

This new novel from Elizabeth Kostova, whose first book, “The Historian,” was years in the making and became a bestseller, is completely different.

“The Shadow Land,” first of all, does not have the frightening suspense of that first book. In fact, it drags at first and begs the question that any young woman in these days is as naive as Alexandra Boyd.

That said, Kostova’s writing is compelling, and when she takes up the story of a labor camp survivor, it is absolutely gut-wrenching. Her vivid descriptions of the countryside illuminate the book and her exhaustive research brings it to life.

Still, the first 160 pages were excruciatingly slow. Alexandra is not just naive, but emotionally fragile and in need of guidance.

The story of her brother’s disappearance and presumed death is tragic, but she continues to blame herself in the most childlike manner.

Jack had become hostile and hateful to the sister he once adored and their parents. When he vanishes on a hike, the entire family is affected — her parents divorce; Alexandra drifts.

She flees her North Carolina home to teach English in Bulgaria, a place Jack had always wanted to see.

Here’s another problem with an essentially interesting novel. Jack’s story is not compelling. It does not provide enough motivation for what Alexandra does, what no other young American woman would dream of doing in a foreign country, especially one whose communist past is very much alive.

Nevertheless, it begins when Alexandra is dropped off at the wrong hotel in Sofia, meets an old man and woman and a handsome, she presumes, son, in a taxi line.

There is a stumble in the trio’s efforts to get in the taxi and Alexandra rushes to help. The inevitable mixup of baggage occurs, and the older group zooms off in one direction while Alexandra is literally left holding the bag.

That she is disingenuous enough to rush around the country with a taxi driver who speaks some English trying to reunite the bag and its owners is a stretch.

Lucky for her, the driver, Bobby, is not a homicidal maniac. He is an educated, slightly bitter young man named Asparuh, who has recently been arrested for protesting against the government, and specifically, against a candidate, Kurilkov, who suggests returning to the good old days of labor camps to get people “employed” again.

Bobby understands Kurilkov wants to corral those who do not follow him, work them to death and then hope they’ll be forgotten.

The bag contains, to Alexandra’s horror, an urn of human ashes. She assumes it is a relative of the older couple, brother to the tall, dark and handsome man.

She and Bobby first go to the police, though Bobby doesn’t like it. So begins their odyssey, Bobby conveniently having time to drive her all over the country and she conveniently having money and no one expecting her anywhere anytime soon.

While the book is a beautiful travelogue of Bulgaria, most of the villages’ names are inventions, though the scenery is not, nor is the political tension.

The intrigue comes as the intrepid duo is followed and frightened by broken windshields, threatening grafitti and trashed homes of those who knew the dead man.

As they meet people related to him, the story becomes more poignant and the threat more real.

The deeply affecting account of the man’s imprisonment, forced labor and lost opportunities, shattered dreams, will keep the reader on the path to learn the truth. Stoyan Lazarov becomes the hero of “The Shadow Land.”

The key to understanding all that has happened and is happening is to remember Lazarov’s torture at government hands is taking place after World War II.

Bulgaria was once part of the Ottoman Empire, then, once free, was overtaken by Russia in the war, and stood behind the Iron Curtain — the invisible wall of communist countries that no one in the West could enter or leave.

People who saw or heard things or asked the wrong questions ended up shot in their homes, dead by the side of the road, disappeared into forced labor camps modeled on German concentration camps.

Political unrest that can lead to death remains an everyday occurrence in places like Bulgaria.

Bobby and Alexandra, whom he calls Bird, travel to address after address, collecting clues, looking behind them, picking up a dog who has a great deal of significance to the story.

They know someone wants something from them, but they cannot imagine why ashes, (or prah, in Bulgarian) are so important. Is it the people they’re talking to, the people they’re looking for who are in danger, or is it them?

Alexandra learns Bobby is a poet and a former police officer. She assumes his distrust of police is because of something he did, but she does not know the whole story, and neither will the reader until the end.

Kostova makes the scenery, the ancient houses, a stone monastery, the sharp mountains and the rushing waters seem impossibly beautiful. It’s summer and hot in the plains, still cold in the mountains.

Kostova also creates characters who have compelling stories to tell, mostly from an arduous past in a country they love.

As the pieces begin to fall into place, the danger quotient climbs.

The climax of the story is riveting, even a little breathtaking.

Kostova should have stopped at that point. Her final chapter, while sweet, is too improbable.

“The Shadow Land” is meticulously researched, and Kostova, who married a Bulgarian and knows a lot about the country, adds authenticity.

Editing would have improved the novel, but if you have time to invest and can excuse the slow start, you’ll be hooked and want to know what happens next.