‘Here I Am’ and here I am not

Published 12:00 am Sunday, October 16, 2016

- Readers have waited 10 years for a new book from Jonathan Safran Foer.

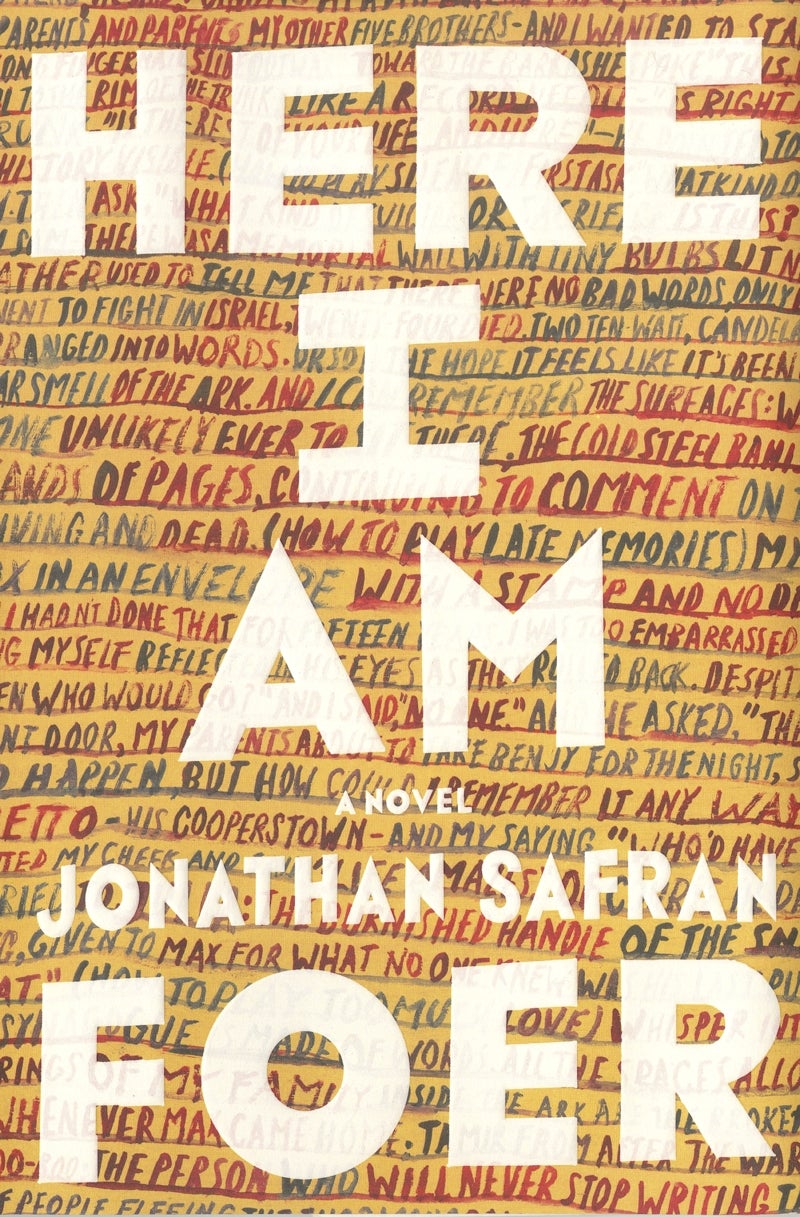

“Here I Am,” by Jonathan Safran Foer. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2016. 571 pp. $28.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

I wanted to be blown away by this author’s new book. His novel of 9/11, “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” remains in my top 10 books of all time.

“Here I Am” is much more difficult to love, or even to categorize. It’s a complex story of a disintegrating marriage, of an earthquake that sparks devastation and war in Israel, of the difference between American Jews and Israeli Jews, of how blind and dumb we are when dealing with each other.

Foer is intellectual and emotional, and so is this book, but there’s no one to like, except the exceptional children, and even they are problematic.

Jacob Bloch is a fortysomething married man who writes for a successful TV show. His mission in life, apparently, is to conceal his happiness, yet long for love and adoration. He hides his real emotions — if he has any.

His wife, Julia, is controlling and precise and wills the family into following her path — for example, the boys’ beds have to have organic mattresses — no artificial ingredients. They must eat a mostly vegetarian diet. She directs her children and her husband, even as she dreams of designing impossible, imaginative houses, which, of course, she never does.

Some critics called “Extremely Loud” and “Everything is Illuminated” “precious.” “Here I Am” is not even cute. It’s filled with pain, overflowing with regret.

Jacob’s father, Irv, is a loud-mouth, outspoken Jewish man who’s never happy unless he has something to complain about or rail against. Jacob’s mother, Deborah, is never fully realized, but she appears to be the rational one.

Jacob’s grandfather, Isaac, is slowly fading away, but resists the idea of being moved into the Jewish Home. Isaac survived when most of his family perished during World War II, horribly. He is scarred, yet loving, more forgiving than his son or grandson, but, again, never fully fleshed out.

His death becomes a pivotal point in the novel, for reasons that even Jacob does not fully fathom.

Of the other characters, there’s little to know or say, except for Jacob’s cousin, Tamir, an Israeli Jew whose oldest son, Noam, serves in the Israeli army.

Tamir, though very rich, and implicitly somewhat shady, has the courage of his convictions, at least, where Jacob has no courage at all and doesn’t even know what his convictions are.

During a rambling conversation between Jacob and Tamir, they first get drunk, then high. Jacob, at least to this reader, repeatedly, willfully, misunderstands Tamir and his very legitimate concerns and feelings.

Jacob has become a character in his own life. He’s secretly writing a script that reflects his life. He’s written a bible for the show— the document that sets the back story, introduces the characters and tells how and what they will play — what they’ll feel, what situations will provoke them.

Jacob no longer lives his life. He’s constantly judging — his own emotions, other emotions — misjudging. He answers questions with questions, then asks a question that has no question to answer it.

He and Julia are unable AND unwilling to communicate. It’s the boys who suffer from the silence, the tension. Young Benjy is a tenderhearted soul with a facile mind. Max, the middle child, is full of questions, but they are more meaningful than his father’s. Sam, the oldest, is facing a bar mitzvah he neither wants nor believes in.

The family is proud of its nonbelief, and equally determined to make the required show — well, Julia and Jacob are.

As Foer writes the story, the lives of Jacob and Julia Bloch are surreal. They don’t inhabit the same plane of reality that the people around them do. They can’t even be unfaithful properly.

A side note — the boys use a great deal of obscene language as if it were as common as the word “the” — Jacob encourages it by his own language. Julia does not react.

So Jacob, for much of the book, seems more unsuited for adulthood than his young sons, less grown up than they are.

When a massive earthquake and subsequent attacks rock Israel, cousin Tamir is visiting the family. Tamir has left his wife and son in Israel. His only thought is of what has happened to them, and how he can get back, while Jacob looks at it all as if viewed through a snow globe — the earthquake, the deaths — are fuzzy and faded. When he suddenly volunteers to go to Israel to fight, the reader is one in a long line of people who do not believe him.

Foer has moments when this book is heartbreaking. He captures a child’s mind so well. The plight of Jewish people in the context of this natural disaster, though fictional, is exacerbated by the ensuing wars. It’s as if Foer, through his flawed characters, is debating with himself. He’s skilled enough, of course, to immerse himself completely in Jacob’s world.

And he’s skilled enough to fool the reader into trying to find a side to take — there are no sides— it’s rough and round and ungraspable.

But in the end, I felt abandoned. So much happens; nothing changes. Jacob is still failing by trying too hard. Julia is as calculated and unreachable as ever. The boys, well, they’re managing. Righteous Tamir never returns to visit his cousin, another abandonment, and Jacob’s parents face the natural decline of age.

The ending scene, with Jacob’s dog, is an emotional gut-punch, but the rest of the story plays out like a televised shouting match, with multiple heads talking. Foer does not provide answers, and, as in reality, there’s no resolution.

The writing, which could be achingly beautiful, is stark and sometimes painfully dulling. Readers may end up wanting to end Jacob and Julia’s marriage just to stop his whining and avoidance and her clamshell of a personality.

Foer examines modern marriage, ambition, child-rearing, faith, Judaism, history, morality and otherness. Its intensity can be wearing. Still, the novel is an experience, in, if nothing else, one man’s writing craft.

After finishing “Here I Am,” the feeling of sadness is strong. It’s the world we live in, Jacob says. It’s the world we live in.