FOOTBALL EDITION: 50 years ago, it was Brinkley to Beck

Published 1:55 am Thursday, August 18, 2016

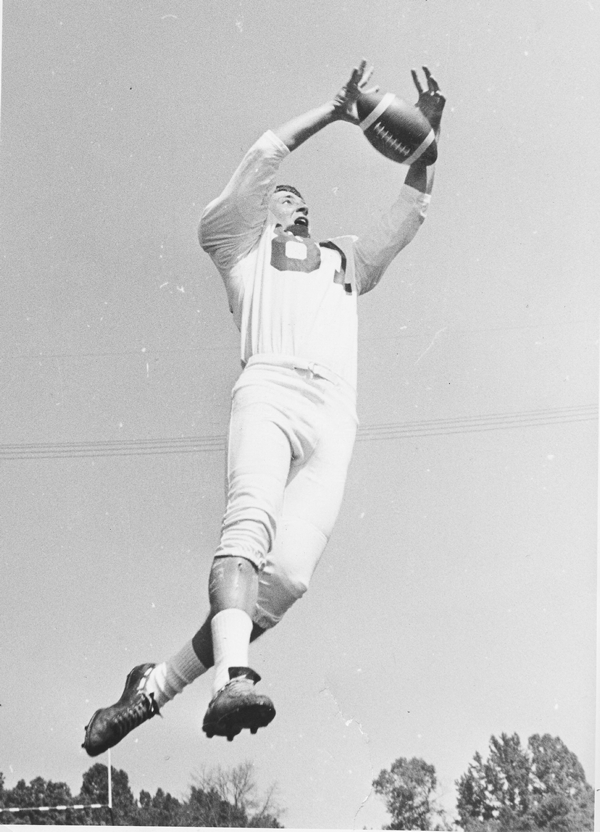

- Salisbury Post file photo North Rowan receiver Ken Beck caught every ball in sight in 1966, including 19 receptions in a single game against Davie County.

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

Fifty years ago, North Rowan’s passing combination of sophomore Melvin Brinkley and senior Ken Beck did things that people still talk about — and that Beck and Brinkley still talk about when they get together for lunch.

High school football is the tie that still binds together Beck, a blue-collar guy who is a Rowan County resident, and Brinkley, a West Point graduate who lives in Greensboro.

“I was just a rough-and-tumble kid, a pretty solid, 180-pound guy who could give a hit and take a hit,” Beck said. “But Melvin was super-smart.”

Beck would hold a state receiving record for 38 years, from 1966 until 2004. Brinkley was the guy who got him the ball.

North Rowan opened in 1958 with Spencer and East Spencer consolidating into a single school. Burton Barger was the head coach for North’s first eight seasons, and the Cavaliers experienced some success, especially in 1961 and 1962 when the program shared North Piedmont Conference championships.

Barger was a believer in the single-wing offense — an old-school, smash-mouth, run-run-run attack that just about everyone used in the 1950s.

North’s new coach for the 1966 season was Steve Yates. Looking to open up the offense and looking to throw the ball more, Yates installed the T-formation, and that was the reason Brinkley became the starting quarterback as a sophomore. Brinkley had limited experience, but his right arm was powerful.

“We didn’t have Little League football back then, so what you learned about the game you basically learned from playing in the backyard,” Brinkley said. “My first organized football games were in Spencer in eighth grade — shoulder pads and helmets, but not full uniforms. Then I played in six or seven games as a freshman. If we hadn’t switched to the T-formation, I wouldn’t have been a varsity quarterback. I didn’t have a driver’s license. I was 15 years old.”

Brinkley knows where his accurate football aerials had their roots.

“Throwing dirt clods,” Brinkley said. “Dirt clod fights with other kids and throwing dirt clods at squirrels.”

Lots of the boys who grew up in that time were farm kids, and they got strong naturally from daily chores and manual labor.

“I never saw a weight until I was a sophomore at North,” Brinkley said. “But you developed a lot of shoulder strength working on a farm, digging holes for fences, things like that. We didn’t have a lot of automated tools. If you needed a hole to fence in some cattle, you used a post hole digger.”

Brinkley’s biggest assets as a sophomore quarterback would be a patient coaching staff — and Beck.

“It’s not like we had a quarterbacks coach — we never had more than three or four coaches total,” Brinkley said. “But we had very solid men coaching us — Yates, Walt Baker, Ralph Shatterly. “I don’t know what would’ve happened to some of us without them.”

While Brinkley knows where his arm strength and accuracy came from, no one knows exactly how Beck became the pass-catcher that he did. Not even Beck can explain it.

“I didn’t have real big hands,” Beck said. “But I did have this natural knack for catching a football. I got to where I could bat a ball with my left hand and then catch it with my right hand. I could catch balls one-handed. And if I got a hand on the ball, it was mine. If we’d had gloves then like the receivers wear now, we would never have dropped one.”

Beck also employed a few tricks, now and then.

“When they taped you up, you’d try to get a little bit of that sticky stuff on your fingers,” Beck said with a laugh. “But you couldn’t let your fingers get wet. Then that sticky stuff would be like butter.”

North’s opening game was against Statesville, a powerful team with Eddie Gamble, Lynn Davenport and Jack McGill, and one of the best teams the Cavaliers would face all season. North led early but lost 39-21 in a game most remembered for a one-handed catch that Beck made for a 38-yard touchdown.

“I didn’t get to see that catch,” Brinkley said. “I got nailed as I threw the ball.”

That was one of Brinkley’s three TD passes in his debut. Two went to Beck. One went to Steve Ward.

“It was a heck of a thing for a sophomore quarterback to have a senior like Ken catching the football,” Brinkley said. “I don’t remember him dropping one.”

North’s third game was a 7-7 tie with Boyden and its first-year coach Pete Stout. The North touchdown came on an outstanding catch by Beck. Legend has it that Brinkley was throwing the ball away when Beck went up and got it, but Brinkley said that’s not exactly true.

“I was rolling to my right, being rushed, and Kenny was across the field,” Brinkley said. “If I’d just wanted to throw that ball out of the end zone, I would’ve done that, but I threw it in Ken’s direction. They had two or three guys on him, but I threw it where it couldn’t be intercepted. He was the only one who had a chance to get it. It’s not like I expected him to make that catch, but he did.”

That tie with a rival that went 6-3-2 would turn out to be one of the highlights of a tough season. North (1-7-2) would drop five tight games, including a 19-14 scrap with Mooresville, a powerhouse that rolled through the NPC without a blemish.

Along the way, Brinkley learned some things, including the jump pass. The jump pass over the middle to Beck became a staple for the Cavaliers and was added to the short sideline routes that Beck ran.

The crowning moments of the season for Beck and Brinkley came in the finale on Veterans Day against a good Davie County team, led by Randall Ward.

“Randall was in one of my groups at the V.A. Hospital not long ago, and we talked about that game,” Beck said.

North lost 13-12, after fighting back from 13-0 in the fourth quarter. The Cavaliers scored with two minutes left and made the PAT to tie, only to see it erased by an offsides penalty. Then the kick was missed, and the Cavaliers never got the ball back.

That game is remembered because Brinkley completed 29 of 45 throws for 240 yards, unheard of stats for that era. The 240 yards were a county record for 10 years and the 29 completions were the county standard for 48 years before East Rowan’s Samuel Wyrick was 36-for-53 against South Point in a 2014 playoff game.

The NCHSAA credits Beck with an astounding 19 receptions in that Davie game. That feat was acknowledged as the state record until 2004 when South Johnston’s Deangelo Ruffin snagged 25 passes in a 53-9 loss to Harnett Central. Beck still owns the county mark for receptions in a game.

“They were mostly short passes that I caught,” Beck said. “And I usually got blasted after the catch. I also had a sore chest. Melvin — he could fire that ball in there.”

Brinkley remembers the jump pass he threw over the middle to Beck for North’s first touchdown against Davie.

“The jump pass was working for us and when something works you stick with it,” Brinkley said. “We were on the 3-yard line and we called the jump pass, but Davie had seen it so much that they knew exactly what was coming. A linebacker yelled out, ‘Watch the jump pass.’ I thought, ‘Oh, great.’ But we didn’t audible, so we still ran the play. We were lined up on the right and Ken was running to his left. They were all over him, and I couldn’t throw it to his numbers. I threw it to his back side, his left hand, and he caught it for a touchdown.”

That disheartening loss was Beck’s last football game.

Brinkley would be a terrific, two-way player for North for two more seasons. He was an all-county defensive back as a senior.

He was tough. He broke his nose twice, broke his hand once, and had his chin split wide open. Through it all, he figures he missed only two plays.

Brinkley would find even greater success as a baseball pitcher.

He threw gas, and he won 27 games in his career for the Cavaliers. He pitched wearing a windbreaker under his uniform jersey. Superstitious, he’d had success wearing a windbreaker on a cold day, so he stuck with it after the weather warmed up.

Coach Gary Jarrett also was superstitious. He kept Brinkley in the cleanup spot in the batting order game after game, even though his batting average was low.

“I had a softball swing,” Brinkley said. “It wasn’t a problem with hand-to-eye coordination, it was a timing thing. But if I hit it, I hit it hard. I hit more doubles than singles.”

In the spring of 1967, Brinkley was almost a one-man pitching staff for a championship team. North was 13-4; Brinkley was 11-4. He fired a perfect game against Mooresville to wrap up the NPC title.

“I was a numbers guy,” Brinkley said. “Mooresville’s cleanup hitter was really good, really fast, and I knew if no one got on base I’d only have to face him twice in a seven-inning game. That’s what happened. Our third baseman (Kelly Sparger) made a great play on a bunt. I got a strikeout for the last out on a 3-2 pitch. It was high, would’ve been ball four, but he swung and missed.”

Brinkley was a key pitcher for the Rowan County American Legion team that finished as state runner-up in 1968 before heading to West Point.

Brinkley would punt for the Army freshman team, but he didn’t get a real chance to play quarterback.

“I could’ve punted for the varsity, but I didn’t want to be just a punter,” Brinkley said. “I didn’t stick it out. I regret that I didn’t. It was a maturity thing.”

He did experience success as a pitcher for Army. He was 4-1 with a 1.30 ERA as a senior. He beat Navy twice.

“They called me ‘Smoke’ when I was throwing hard and “Blue Smoke’ when I was throwing harder,” Brinkley said.

Brinkley got to pitch against the New York Yankees in an early 1970s exhibition game, just one of the memories he has of a fine career.

Things went less smoothly for Beck, who was supposed to play football for Gardner-Webb after his North career ended.

“I broke my hand playing basketball right before I left — one of the big girls who played for North fell on my hand,” Beck said. “I was wearing a ring, and they had to cut it off my hand before they could fix it. I reported to Gardner-Webb with my hand in a cast, and the coaches weren’t very happy with me. They call that town where Gardner-Webb is Boiling Springs for a reason. Oh, it was hot there. I practiced with the team but never played.”

Beck was in the Marine Corps not long after that, and then he was headed to Vietnam for 13 months. He made it back in one piece.

Beck kept playing softball until he was 50, and he played golf for years after that, but he’s not in good health now. He’s had a triple by-pass and usually motors around on a scooter.

“I try to mow grass and weed-eat, do some of the things my wife shouldn’t have to do, but I always pay for it the next day,” Beck said. “I can’t run around with my grand-kids, and that makes me sad.”

He has the film of the Statesville game, and the one-handed grab, but he doesn’t have film of the Davie game. He’d love to see that. He’s still convinced it was a game North should’ve won.

While it’s been 50 years since his glory days, Beck’s mind travels back to his youth whenever he sees North Rowan.

“My youngest daughter went to North and played in the band, and when I’d go out to the stadium for a game, it was almost too emotional for me,” Beck said. “I can forget something now just walking from the den to the kitchen, but I can still go out to that football field and point out spots where Melvin threw me a pass.”

Beck doesn’t watch sports on TV much anymore. It’s just not the same when an athlete becomes a spectator.

“I might watch the World Series or Super Bowl, but that’s about it,” Beck said.

Still, he doesn’t mind at all talking about 1966 when they called him “Ken, the End”, and it gives him a shot of adrenaline chatting about all those receptions. His ego isn’t large, but it’s still gratifying when someone remembers what you did 50 years ago and reminds the youngsters about it.

“I hope people will remember how good he was,” Brinkley said. “Kenny caught everything.”