Spencer’s search continues for more Dixonville Cemetery names

Published 12:03 am Wednesday, September 16, 2015

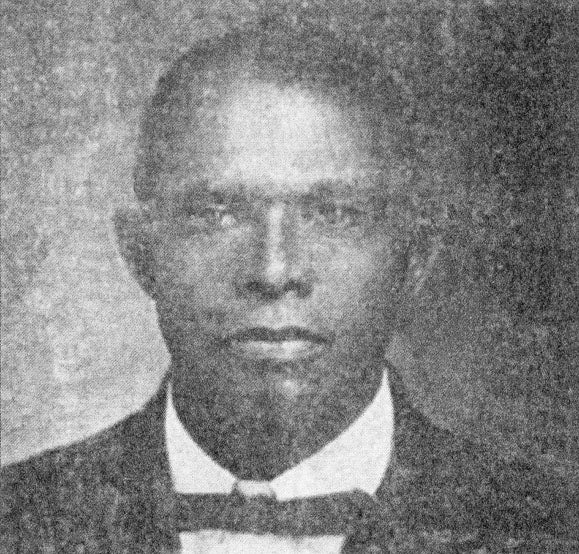

- Submitted photo The Rev. John Pless Alexander, buried in the Dixonville Cemetery in 1934, was a minister and shoemaker who had a shoe shop on East Council Street for 46 years.

SALISBURY — Betty Dan Spencer still becomes mesmerized, captured in the stories of people buried in Dixonville Cemetery.

John Pless Alexander, who was buried in Dixonville in 1934, was a minister and shoemaker. He lived on South Shaver Street and had a shoe shop on East Council Street for 46 years.

But he was a minister even longer — 53 years, and 39 of those years he spent traveling Sunday mornings to New London where he was pastor of the African-American First Baptist Church.

The Rev. George W. Austin, a Baptist minister, was born in Monroe during the Civil War. He became a popular teacher at a black public school in Salisbury, and the Salisbury Evening Post said the service at his death in 1920 “was one of the largest attended Negro funerals ever held in the city.”

The monument for Austin, his wife, Mary J. Hancock, and their infant son Benjamin F. Austin is one of the nicest remaining tombstones in Dixonville Cemetery, which is located next to Lincoln Pool along Old Concord Road and is the city’s oldest African-American cemetery.

The Dixonville-Lincoln (School) Community Association will meet for one of its regular reunions at 6:30 p.m. Saturday at First Calvary Baptist Church, just up the street from the old cemetery.

Spencer, a local historian who in 2008 published the book “Remembering Dixonville and East End,” will be attending the reunion hoping more people will come forward with information about who else might be buried in Dixonville.

It’s not that Spencer is starting from scratch. Over the past 10 years or so she has used funeral home records, death certificates, newspaper obituaries, the Census, marriage licenses, mortality schedules, draft registration cards, deeds, wills and more to determine who is buried in Dixonville and flesh out some of their biographies.

“I’m approaching 500 names,” she says, and they are meticulously documented in several heavy notebooks which include, when available, newspaper clippings and photographs.

She’ll have those names at her fingertips Saturday, hoping they create leads into others.

There is some frustration in Spencer’s passion for finding out as much as she can about Dixonville Cemetery. Only 28 monuments or pieces of monuments remain in the cemetery, which hasn’t had a burial since the 1960s.

“When I was a child,” Spencer says, “the place was full of tombstones — it was full looking.”

Spencer also believes the main burial years in the 2-acre tract were between 1874, when it became a city-owned cemetery, and 1910, three years before death certificates were required to be issued. In those days, too, Spencer says it was unfortunate, but few African-American obituaries were printed in white-controlled newspapers.

“All these people are just lost in time,” Spencer says.

In short, many more Salisbury residents are believed to have been buried in Dixonville than the close to 500 Spencer has been able to document so far. The earliest known burial was that of Mary Valentine, whose marker was uncovered by city workers in 2007. Valentine, a free woman of color, died Oct. 14, 1851, according to the tombstone.

According to Spencer’s research, Joseph Horah owned the land that would become the Salisbury National Cemetery and the Dixonville Cemetery.

During the Civil War, Horah allowed the Confederate government to use his cornfield to bury Union prisoners who died at the Salisbury Prison. Spencer thinks it’s likely Horah also permitted African-Americans to be buried on his property before the city purchased the acreage in 1874 and continued burials.

In 2010, then Mayor Susan Kluttz called for establishment of a new task force and asked it to develop a memorial design for Dixonville Cemetery and a fundraising plan in partnership with the city.

The Dixonville Cemetery Memorial Project Task Force is still working, and costs associated with installing a Dixonville memorial have varied widely. In 2014, the price tag shared with City Council was as much as $348,000.

Meanwhile, Spencer still wants to know more about the people buried in Dixonville Cemetery, especially for the day the memorial project finally takes shape. Her research already reveals many important people in the city’s history are buried there.

They include Bishop John Jamison Moore (1818-1893), who founded the AME Zion Church in western North Carolina. Moore’s Chapel AME Zion church is named for him.

The Mary Valentine tombstone raises questions as to whether all the other Valentines also are buried in Dixonville. William Valentine was, for example, one of the most influential African-Americans in Salisbury during the Civil War era and afterward.

Spencer notes that Clarence Williams also is interred in Dixonville. He was a longtime, popular orderly at Rowan Memorial Hospital. When Williams died in 1952, his death made the front page of the Salisbury Post.

John “Jack” Mowery (1836-1902), one of Spencer’s favorite subjects, was a tailor by profession who became a pretty good entrepreneur. He owned the East Fisher Street building, now under restoration, that most recently was home to Benchwarmers. In earlier days, the Noble & Kelsey Funeral Home operated on the second floor of that same building.

Spencer also is fascinated with Lydia Davis Henderson, who died in 1913 at age 74. She was born in Fayetteville in 1839, and in the three years before her birth, her mother Carolina Davis’ master, D.A. Davis, was appointed by the Bank of Cape Fear to manage a branch office in Salisbury.

That bank was on the corner of Main and Bank streets, and D.A. Davis would become a leading citizen of Salisbury and an elder in First Presbytrian Church. According to Lydia’s obituary in 1913, she was 15 years old when she went to live with the John Dickson Brown family and became the nurse and “mammy” of Ella Williams Brown.

Later in life, she had similar duties for Alice Slater Cannon. Lydia died at the South Fulton Street residence of Mrs. David F. Cannon. The Salisbury Post obituary ‘s headline announced her death as “The Passing of a Good Woman.”

“Here, in the home, as one of the family,” the obituary said, “she spent her last days in peace, ease and luxury, receiving the best medical care and attentive nursing. She was honored and beloved by every member of the family.”

Spencer once lived in the same South Fulton Street house where Lydia had worked for the Cannon family. Yes, it’s easy to get lost in the people of Dixonville.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263.