‘Miracle Girl’ – it all depends on what you believe

Published 12:00 am Sunday, September 13, 2015

- 'The Miracle Girl' swarms with unanswered questions.

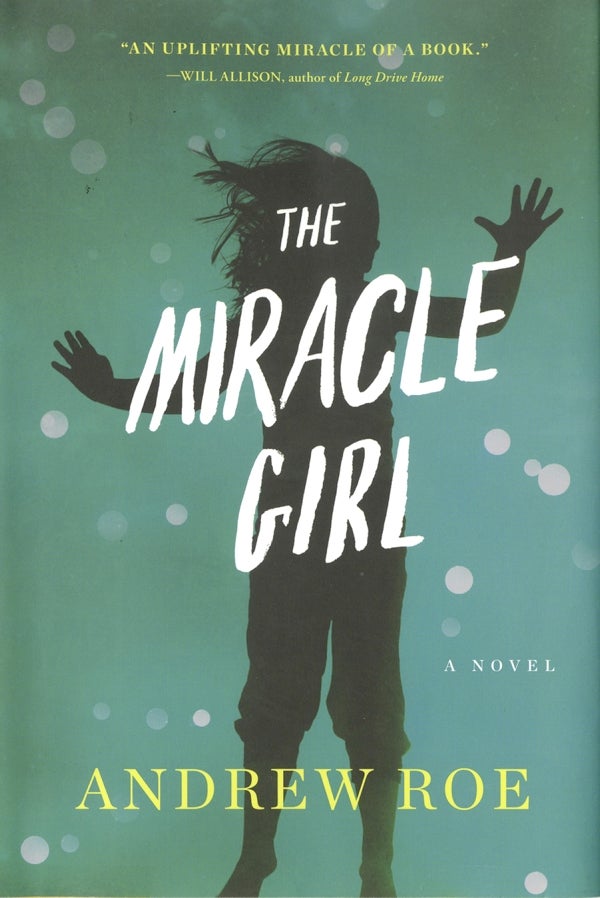

“The Miracle Girl,” by Andrew Roe. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. 2015. 320 pp. $24.95.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

There’s a strong dose of skepticism in “The Miracle Girl,” by Andrew Roe. And a strong dose of desperation, all brought on by the girl, Annabelle Vincent.

To set the stage — for this is very much a stage piece — Annabelle is an 8-year-old suffering from akinetic mutism after a horrible car wreck. Unable to move or speak, she lies in a bedroom full of medical equipment and the smell of roses.

The scent of roses has long been associated with miraculous events.

Roe based the book on the true story of Andrey Santo, a brain-damaged girl from Massachusetts credited with miracles.

But he wondered, “What if the family did not have religion or faith, as the Santo family did.”

The book opens with Karen and the few helpers she has, her husband John long gone, and she remembers the visit from a family friend, who prayed alone in Annabelle’s room. Stricken with leukemia, the friend is prepared to die. She later learns that the cancer is gone.

With John running away from his guilt, Karen is left in their tiny house in a downtrodden section of Los Angeles with Annabelle and a growing line of strangers outside the door.

Odd circumstances to be sure. Karen gets help from a niece and a nice guy named Bryce, who fully believes in Annabelle’s miraculous powers. A physical therapist, Linda, tends to Annabelle’s body, believing in her own powers.

Roe tells us what it’s like to live with a miracle, a miracle whose room is full of stuffed animals and flowers and balloons and something no one can explain.

Imagine Karen, shell-shocked first from the horrendous accident that leaves her only daughter close to death. Imagine Karen fighting to keep her daughter at home instead of tucked away in a facility. Imagine her feeling of desperation when John leaves. Imagine the endless days and nights when Karen deals with the curious public and the demands of her daughter’s condition.

Karen lives for Annabelle. For herself, she merely subsists, with short naps and grabbed snacks. Sleep has long since left her. Her body’s hunger has been forgotten with the stress of just getting through another hour and another hour and another.

Karen doesn’t know what to think about Annabelle’s supposed miracles. She doesn’t quite believe it, but she doesn’t quite disbelieve. She exists in another realm, the cocoon around her precious daughter. She can’t turn people away, and she can’t answer their questions. All she can do is love her child.

Once the media discovers Annabelle, Karen becomes a talking head, answering the same questions over and over.

John, meanwhile, hopes from job to job, trying to escape his guilt and fear. What money he makes he sends to Karen and Annabelle. He wants no one to know who he is or who he left behind.

Roe, then, creates the atmosphere of doubt and confusion, of loss and desperation. Using a a third person narrator, Roe goes into Annabelle’s head — she’s remembering how things were, how she liked to make up words, how she preferred to be alone, in her fertile mind.

Karen remembers that Annabelle was an inconsolable baby, crying non-stop. John remembers his daughter not acting like other children, always distant and different.

When the Catholic church is asked to start an investigation, it is with a well-placed doubt that this girl is responsible for miracles.

Oddly, even though Roe introduces the investigating priest and hints that he is a gentle, open-minded soul, readers never know what Father Jim Hinshaw believes.

Roe also takes readers into the minds of the people waiting outside the house, in an unusually hot and rumbling LA. He writes of the inner struggles of those hoping against hope for a cure, a resolution, happiness.

He even shows John’s change of heart, as, haunted by his true responsibilities, he faces up to what love is really about.

Karen and John are ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. How does anyone handle things that are so completely out of their control? That’s the question Roe is posing. And, just like anyone, he has no answer, not even in fiction.

As the needs grow greater and Karen feels stretched beyond imagining, she decides it must stop. She plans a last viewing, in a high school football stadium, of Annabelle, and then, it will be over. No more strangers, no more TV cameras, no more investigations by the church and skeptics.

As the day approaches, there is a sense of something ending and beginning. The reader may worry about a final cataclysm, what with the heat and frequent earthquakes, the crush of people.

Then something happens — perhaps the bona fide miracle — and life moves on. The church issues a statement. Time passes, people grow and change. Just like always.

But Roe suggests, for a disbelieving, despairing world, that anything is possible.