‘They started popping bullets’: Eyewitness recalls the day Otto Wood died

Published 12:25 am Thursday, July 30, 2015

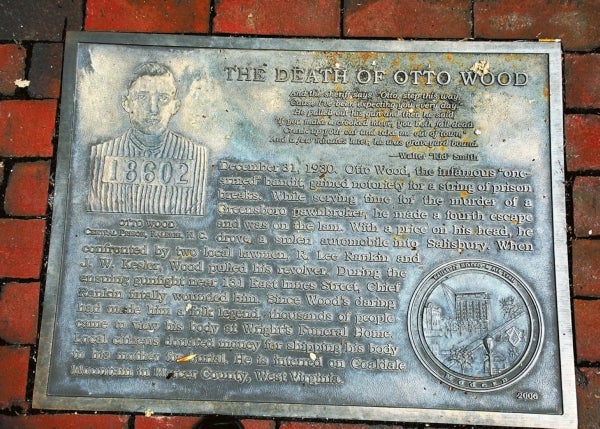

- Mark Wineka/Salisbury Post This sidewalk marker at 131 E. Innes St., describes the shootout in Salisbury that took notorious bandit Otto Wood’s life on Dec. 31, 1930. It is part of Salisbury’s History and Art Trail.

He pulled out his gun and then he said,

“If you make a crooked move, you both fall dead.

Crank up your car and take me out of town,”

And a few minutes later, he was graveyard bound.

— “The Ballad of Otto Wood” by Walter “Kid” Smith

THOMASVILLE — From their farm in Woodleaf, William Raymond Barbee and his wife, Pearl, piled the children into their Model A and drove to Salisbury.

It was the last day of the year — Dec. 31, 1930 — and Barbee, who friends called “Raymond,” had to renew his license plate before it expired with the new year.

As his son Brady Barbee remembers it today, the license tag office was on Council Street, but Raymond parked the car on East Innes Street in front of O.O. Rufty’s General Store.

He’s not sure whether his father already had renewed the license tag or was headed there, but he’s pretty certain they stopped at the general store for candy. Besides Brady, the other Barbee children then included brothers Lee, Martin and Don and sister Irene.

The Barbees were outside the store next to their Model A when the shooting began.

Raymond Barbee let out a shout.

“He hollered for us to ‘Duck! Duck! Duck!'” Brady says. ‘With something like that going on, there ain’t no reason to duck.”

What was going on was a honest-to-goodness shootout on the street and sidewalk near the Yancey Building at 131 E. Innes St. The Barbees had no way of knowing, but Salisbury Police Chief Lee Rankin and Assistant Chief J.W. Kesler had confronted Otto Wood, one of the state’s and nation’s most wanted fugitives.

The situation became testy when Rankin called on Wood, who had lost his left hand in a hunting accident, to show him that arm. Wood drew on the officers first and actually climbed into their car before Rankin decided they were going nowhere.

“They started popping bullets,” Brady Barbee says. He was 7 years old then, but it was something you don’t really forget. “There were a bunch of shots fired.”

Accounts said at least 11 shots rang out. When it was over, the 36-year-old Wood lay dead, and the Barbee family had something to remember for the rest of their lives.

“Yeah,” Brady Barbee says, “it was like a western, and, no, we didn’t think about being scared. When he hit the street, he was dead.”

As he recalls, the shootout took place near the Yancey Building, the longtime home of Hardiman Furniture. There’s a Thai restaurant in the building today. Brady Barbee also remembers a car parts business next to it.

On a recent Saturday afternoon Don Barbee of Salisbury visited his older brother Brady at the Piedmont Crossing care facility in Thomasville. Don’s daughter Jane also made the trip.

It can’t be said with absolute certainty, but Brady Barbee might be the last living eyewitness to the Otto Wood shootout. Don Barbee was a 3-month-old baby at the time, being held in his mother’s arms as the ruckus took place.

Otto Wood was the stuff of legend, a Depression-era desperado whom you would write songs and outdoor dramas about, and Walter “Kid” Smith of the Carolina Buddies and Jerry Lankford of the Record newspaper in North Wilkesboro did, respectively.

Wood was a gambler, bootlegger, car stealer, robber, killer and frequent fugitive from justice. He escaped prison four times and was at large again in 1930. He had been convicted in 1923 of killing Greensboro pawn shop owner A.W. Kaplan.

Wood reportedly was in Salisbury with a friend, Roy Barker, to rob the same license plate office Raymond Barbee had come into town that day to visit. It was a cash business, and Wood probably saw it as a prime target because of all the people who would have waited until the last day of the year to renew their plates.

Here’s an account of what happened leading to the shootout.

That day, Wood and Barker had parked their stolen 1930 Ford on East Innes Street, and they ate lunch at the Salisbury Cafe on East Council Street. About 1 p.m., someone stopped by the Salisbury police station to tell Rankin that Wood was in town, though little credence was given to the report because Wood sightings were common across the state.

But Rankin and Kesler agreed to conduct a short search. From their car, they called out to two strangers walking down East Innes Street in front of the Yancey Building at 131 E. Innes St.

“Come here, buddy, we want to see you a minute,” Rankin said to one of the men, who turned out to be Wood. He and Barker approached the chief’s car, but when Rankin asked to see Wood’s left hand, which was concealed, Wood pulled out a .45-caliber pistol.

“Yes, I’m Otto Wood,” he said. “What the hell are you going to do about it?”

Wood and Barker climbed into the back of the chief’s car and ordered the officers to drive them to the train station.

The newspaper account said, “Chief Rankin did some fast and capable thinking, and moved as if to obey. He fumbled for a moment with the switch and then literally tumbled from the car as he jerked the door open, the keys being in his hand so that Otto could not drive away.”

Rankin apparently made it to the front of the car and began firing, sheltered by the radiator and fender. Wood and Barker exited from the back of the car quickly, while Kesler also was jumping out, managing to fire twice.

“Chief Rankin raised up over the radiator, and he and Otto fired simultaneously at each other at close range, Rankin’s bullet striking Otto in the right cheek and sending him to the ground.”

In all, Wood’s body would have four bullet holes.

Don Clement Jr., who recently died, was a 9-year-old at the time of Wood’s shooting, and he once recalled for the Post how he walked up to Wood’s lifeless body while it was still lying in the street. He noted that Rankin had not been hit, but windshield glass had been shot out and flakes of the glass had bloodied the chief’s face. Clement’s dad retrieved the chief’s hat.

Wood’s body was taken to Wright’s Undertaking, where it was put on display, The Post gave this report: “Thousands of persons, some estimates placing the number as high as 20,000, have filed past the bier of Otto Wood. Otto’s left arm, minus a hand, has been the subject of much comment, while the three upper front gold teeth have also been prominently noted.”

Wood’s brother came to Salisbury Jan 2, 1931, to claim the body but left because he didn’t have the money to ship it. Salisbury citizens raised $24.68 to send Wood’s body to his mother, Ellen, in Coaldale, W.Va.

Salisburians also contributed an additional $39.44 to the mother to help her bury her son. They are buried together on Coaldale Mountain in Mercer County, W.Va.

Barker, Wood’s buddy that day in Salisbury, was sentenced to six months in prison for carrying a concealed weapon.

Salisbury has a History and Art Trail marker at 131 E. Innes St. describing the Otto Wood shootout. The Rowan Museum also has the gun Rankin used to kill Wood.

Brady and Don Barbee say their parents, Raymond and Pearl, fussed at each other over Wood as the years passed. Pearl Barbee didn’t like the way Wood’s body had been treated after the shooting, especially when his head was picked up and allowed to fall against the pavement, Brady says.

Though the farm family probably couldn’t afford it, Pearl Barbee contributed some money toward Wood’s burial.

Many people in Rowan County might know Don Barbee as the retired postmaster in Woodleaf. Brady Barbee did a little bit of everything. He worked as as salesman, planted cotton and operated a dairy farm.

But he says he found his niche when he bought a bulldozer.

With his bulldozer, he cleared a lot of land, dug out pipelines, etched out road beds and built many fish ponds. “We hit it just right,” Brady Barbee says.

Don Barbee has never lost his interest in the Otto Wood story. He has attended Lankford’s outdoor drama in North Wilkesboro three different times.

His daughter Libby’s husband, Tom Owens, worked with contractor Bob Glover during restoration work on the old Hardiman’s Furniture a few years ago. Don and Brady think Tom Owens was able to dig out and recover a few bullets in the exterior wall from the 1930 shootout.

Tom Owens says it never happened. That rumor probably started, Owens says, when the work crews were taking off a facade to expose the original wall and someone said, “There might be bullet holes back there.”

If anyone had found bullets, Owens says, the newspaper probably would have been contacted.

“When I heard that, I busted out laughing,” he says.

Meanwhile, the Barbees still have their Otto Wood story. Brady Barbee laughs himself, thinking about how his father yelled three times for his family to duck.

“There weren’t no ducks around,” he says.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263, or mark.wineka@salisburypost.com.