Man of honor: Navy diver Dowd Dunn Sr. proud of his career

Published 12:10 am Monday, May 25, 2015

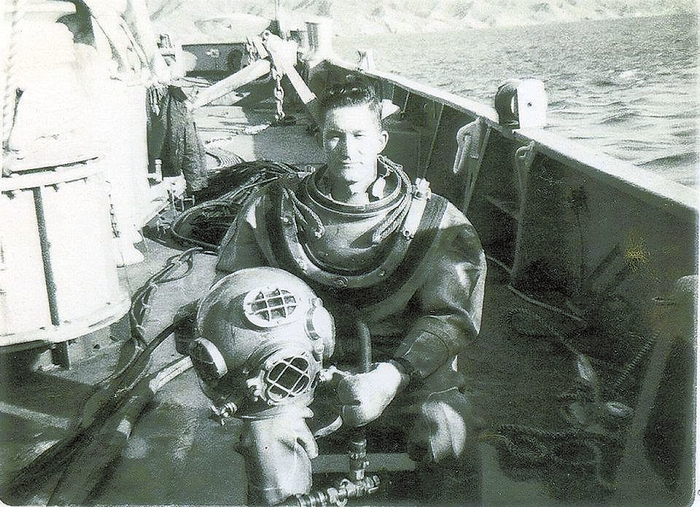

- Submitted photo This photo from the late 1950s or early 1960s shows Dowd Dunn Sr. in his Navy diving gear, which weighed 197 pounds.

ROCKWELL — Dowd Dunn Sr. straightened up in his favorite chair and leaned closer when the movie was mentioned.

“Men of Honor” told the real-life story of Carl Maxie Brashear’s struggle with racism and how he overcame the loss of a leg to become a master diver, the highest designation a Navy diver can attain. In the 2000 movie, actor Cuba Gooding Jr. played the role of Brashear, whose left leg was crushed and eventually amputated after an injury on a salvage ship in 1966.

“Oh, yeah, he was a friend of mine,” said Dunn, now 82. “I went to school with the man. … He had to make the same dives I did, and I had to make the same dives he did.”

Brashear and Dunn attended salvage training school together and later went on several of the same jobs. They were on the same salvage mission in 1966 off the coast of Spain when the accident occurred leading to Brashear’s loss of a leg. The ship’s name was Hoist, and Navy diving teams were trying to find and recover a hydrogen bomb that had sunk into the Mediterranean Sea after a plane crash.

Dunn was in the water searching for the bomb when Brashear’s accident happened. Brashear was supervising from the ship when a line broke and a steel pipe went flying toward the men on the deck. Brashear was credited with pushing other men out of the way, but the pipe destroyed his leg, which he later lost at the Portsmouth Naval Hospital in Virginia.

Against all odds, Brashear worked hard to become the first Navy diver restored to full active duty as an amputee. He retired in 1979 as a master diver and died in 2006.

“Carl was a good man,” Dunn said, “and there was some prejudice.”

Still, the movie also took a lot of liberties with Brashear’s story, Dunn said. “They (the Navy) didn’t treat us that way — that’s Hollywood.”

•••

When he moved back to Rowan County in January, Dowd Dunn Sr. asked the landlord of the little house he was renting on Gold Knob Road whether he could install a flagpole in the front yard. It was one of his first priorities, and today he proudly flies the U.S. and Navy flags from the tall pole in front.

“He’s proud of his service, and I’m proud of his service,” said oldest son Steve Dunn, a Navy veteran himself.

Dowd Dunn lives with his faithful dog, Bear. Meanwhile, all of his family — five children, eight grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren — are close by. Dunn lost his wife, Carole, to leukemia in 2000.

Dunn served in the Navy from Jan. 9, 1952, to July 9, 1971, and 16 of those years he was a diver, a dangerous occupation that qualified, along with sailors on submarines, for the higher hazardous combat pay. Dunn said he personally had no close calls, and he only had to “ride” the decompression chamber once after coming to the surface too fast.

He has no idea how many times he went under the water in the Navy but assumes the number must be in the thousands.

“One reason he could do all that diving,” Steve Dunn said, “was that he had a high threshold for pain.”

After his Naval career, Dowd Dunn returned to Rowan County and worked for Desco Lighting for seven-and-a-half years before relocating to Georgia for more than three decades. It was a good place to hunt and fish, and Dunn worked for two hospitals, besides going to emergency medical technician’s school and fire science school and becoming a nationally recognized first-responder.

He also became his county’s deputy EMS director. But it was Steve who kept harping on his father to come back to North Carolina so he could be closer to all of his family.

“He wouldn’t leave me alone,” Dowd Dunn said, chuckling.

•••

As a boy, Dowd Dunn lived for a time in Mount Holly and Charlotte before his family moved to the Dukeville community of Rowan County when he was in third grade. His father, who also was a minister, worked at the Buck Steam Station.

Dunn attended Dukeville grammar school and Spencer High School through the 10th grade until his family moved across the river into Davidson County. His father founded and built, with some of Dowd’s help, Lakeview Baptist Church.

Dunn graduated from Churchland High School in 1951, and he joined the Army National Guard in Lexington. Because of the fighting in Korea, the unit faced activation, and the reservists were given the option of enlisting in other branches of the military, if they wanted. Dunn decided on the Navy, only because his father and an uncle had been Navy men themselves.

Dunn took the long train ride to the Naval Training Center in San Diego, Calif., and his first assignment was on the the USS Virgo, which was serving as an ammunitions ship, replenishing United Nations naval forces operating off the Korean coast. The Virgo fell into routines of replenishing carriers, battleships and destroyers at sea, going in and out of Korean and Japanese ports and going back to the West Coast for overhauls.

Sometimes Dunn would get a 30-day leave, which he usually spent in Oakland. He and two of his buddies attended a Baptist Church every Sunday, and it was in church Dunn met Carole. The family story goes that when Carole first noticed Dowd from across the sanctuary, she told her sister, “I’m going to marry that man.”

“I talked to her sister before I did her,” Dowd said with a laugh.

Their courtship lasted all of four months, and they were married in 1953. Dunn said Carole was a special woman, putting up with his unpredictable, dangerous life as a Navy diver, not to mention his sporting passions.

“I fish and I hunt, and I went fishing on our honeymoon in the redwoods of California,” Dunn said.

By 1955, the Dunns had two children, Steve and Cheryl, both of whom were born in California. Three more children would arrive by 1961 — Mark, born in Jersey City, N.J., and Dowd Jr. and Kathi, both born in Salisbury.

After the fighting in Korea ended with an armistice in July 1953, the Virgo still made trips between the West Coast and U.S. bases in the Far East. Dowd Dunn’s interest in diving took root one day when the Virgo was sweeping the Sasebo harbor for mines. Its equipment hit a snag, and the Virgo needed divers’ help in lifting it free.

“The way they worked together — the crew, everybody was doing something,” Dunn recalled of the diving ship. Making the necessary inquiries and obtaining the right OKs, Dunn was soon working off a main diving ship and taking four weeks of training to become a second-class diver on the USS Grasp.

His diving gear — accentuated by the huge helmet, shoes and belt — weighed 197 pounds. The first exercise he had to complete on his own was in about 50 feet of muddy harbor water where “your hands are your eyes,” he said. Dunn found that he had a passion for diving, the teamwork needed to keep everyone safe and the thrill of salvage and rescue missions.

Over his career, Dunn trained at three more diving schools and would reach depths of hundreds of feet. He rose to first-class diver status, and over his last three years, served as an instructor, often training Navy SEALs.

•••

The life of a Navy diver is one in which the men are always on call.

“They told us to keep our bags packed, and we did,” Dunn said.

The salvage mission off the coast of Spain in which Brashear was hurt was a good example. Dunn said he and the other divers were flown out of Norfolk in that case.

Dunn also served as part of the diving recovery team on alert during takeoffs of Gemini and Mercury space missions out of Cape Canaveral, Fla. They were never needed, but Dunn’s team of divers were available for rescue operations in case one of the rockets went down within the first 90 seconds of takeoff.

The one time Dunn had to go into the decompression chamber came in the Pacific when he was underwater, working on an offshore fuel line. He lost balance when a tide swept in and pushed him quickly toward the surface. To allow for the nitrogen build up to escape his system properly, Dunn should have gone up to the top in stages.

He knew something was wrong on deck. “It didn’t hit me until I went to get a cup of coffee,” he said.

Dunn was placed in the big steel chamber for 27 hours, starting out at a pressure that was 40 feet below where he had been in the water. “That’s the only time I rode the chamber,” Dunn said.

Steve Dunn said it was sometimes tough being a diver’s son.

“One minute my daddy’s there, and the next he’s gone,” he said.

Steve ticks off the various states the Dunns lived while Dowd was in the Navy — California three times, New Jersey, North Carolina, Florida and Virginia. With five children, Navy housing was always the cheaper way to go when it was available.

Steve was a junior in high school when he father retired and moved the family back to Rowan County. Steve would end up graduating from West Rowan High in 1972 before entering the Navy and becoming a sonar technician on a submarine. His father’s career in the Navy was a big influence, of course. Steve served four years.

Dowd Dunn is glad he relented and moved back to North Carolina, putting him closer to everyone.

“I don’t regret it, let me put it that way,” he said.

As for his Navy diving career, there are no regrets there, either.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263, or mark.wineka@salisburypost.com.