Barbecue in the Carolinas, from shoulders to hogs to vinegar and mustard

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, May 12, 2015

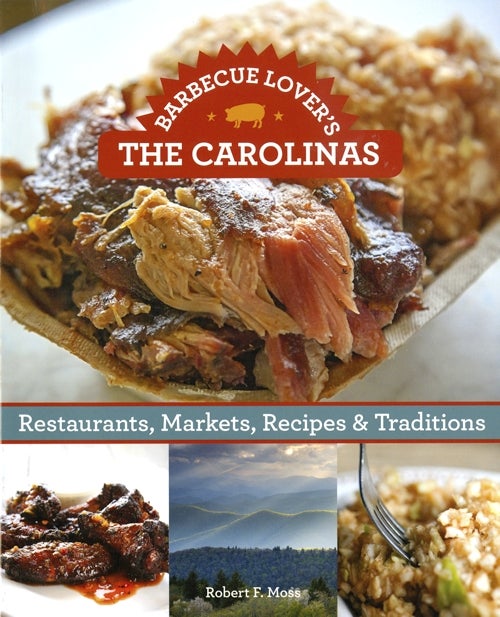

- 'Barbecue Lover's: The Carolinas,' by Robert F. Moss, covers traditions, regions and recipes.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

Here comes another book purporting to cover barbecue, barbeque, Bar-B-Que and BBQ in the Carolinas.

Well, let’s get serious. You would need multiple volumes to do that — one for each style of barbecue in the different regions. You could do one volume alone about Lexington.

Robert F. Moss, a food and beverage writer in Charleston, S.C., has written “Barbecue Lover’s: The Carolinas: Restaurants, Markets, Recipes & Traditions.” He has some props. He wrote “Barbecue: the History of an American Institution,” and he writes for the Charleston City Paper, Garden & Gun and the Charlotte Observer, among others.

Here’s his slant — he is from Greenville, S.C., and went to Furman University and the University of South Carolina.

You may notice a more South Carolina flavor to this book. And we all know that South Carolina barbecue has that odd color from the addition of yellow mustard.

South Carolina also serves hash and rice with their barbecue, where we have slaw and hush puppies.

Hash, Morris writes, was originally a way to use leftover parts of the pig, such as the liver or the head, even lungs in some instances. Now, he says, cheaper cuts of pig, such as pork shoulder and hams are used, and in the Upstate, you’ll find chuck roast or other beef cuts. The key is a long, slow simmer with water, onions and spices until the meat falls off the bone or shreds into threads.

But back to us, the Old North State, where we eat the real thing — yes, them are fightin’ words.

Morris writes that the Carolinas have the oldest continuous barbecue tradition in the U.S, dating to colonial time. In Carolinas, barbecue means pork, slow cooked over smoke and served chopped fine in most cases.

In other realms of the U.S., barbecue means anything cooked on a barbecue grill, from hot dogs to chicken to fish.

Morris admits his volume leans toward places that still cook over oak or hickory, not so much the gas cookers.

He also makes another valid point: Call ahead and see when the place is open, because some of the smaller, off-the-beaten path joints (barbecue restaurant is too hoity-toity) are only open a few hours or days of the week and some close once they run out of food.

Morris says South Carolina lays claim to the invention of barbecue, but native Americans were already cooking meats over green wood when we arrived. Historians say it came from the Caribbean, with the Taino Indians, where the frame and green sticks were called baribicu, which became barbacoa in Spanish and barbecue in English.

In 1709, John Lawson wrote about a barbakue of fish in North Carolina. And it’s mentioned again in 1737 when John Brickell noted Native Americans drying salted venison and cooking wild turkeys over coals.

Like so many things in Colonial days, Virginia was the center for barbecue, which spread south to the Carolinas. Charleston, which enjoyed more formal, refined meals, doesn’t mention barbecue until the late 18th century.

But, back to the present. Morris shares a great deal of history throughout the book, putting barbecue and its tradition into context.

He lists barbecue contests in both states and then he gets serious, diving into the regional differences in barbecue, starting with eastern North Carolina and the Pee Dee region of South Carolina. He says this barbecue has a lot in common with colonial tradition. Whole hogs are cooked on open pits with hardwood coals, basted frequently with a vinegar-pepper sauce and chopped all together. The sauce is likely to be simple, vinegar, salt, black pepper and red pepper, generally cayenne. It’s served with white slaw and corn sticks, not hush puppies.

It’s in this area you’ll also find Brunswick stew as a side dish, which dates from the 1820s and then was a way to cook squirrel. Later, corn, tomatoes, onion and potatoes were added.

He lists barbecue joints with descriptions of the food and atmosphere and photos that embody the imagined barbecue joint, low slung building, white siding or cinderblock.

Then he visits the Piedmont, where, sure enough, he picks two places here in Salisbury — Richard’s and Wink’s. We all know plenty of other places and everyone has a favorite — College, Gary’s, Hendrix, to name a few. He proclaims, “Trying to identify all the good barbecue joints in the Piedmont of North Carolina is sort of like trying to count the fish in the ocean.”

He continues, “The region teems with hickory-smoked pork, and what passes for second-tier barbecue in towns like Lexington and Salisbury might well be considered the best ‘cue in a three-county radius if it were found somewhere else.”

The Piedmont is the place for shoulders, which tend to have more fat and are juicier than other parts of the pig. The sauce is similar to the Eastern version, with additional tomato in the form of ketchup and that hint of sweetness.

Chip Stamey of Stamey’s in Lexington told Morris that they have better uses for a whole hog, like bacon and ham, and the shoulder was the least expensive part.

It’s the place to find red slaw and hush puppies. He correctly declares that Cheerwine is the drink of choice for barbecue.

His short piece on Richard’s mentions their coleslaw (yummm) and their onion flecked hush puppies (yummm) as well as their wood-fueled pit.

There’s a sidebar about Keaton’s — “Not Exactly Barbecue, but Damned Good Chicken.”

And finally, he writes about Wink’s, King of Barbecue. He likes their breakfast, especially their sausage gravy, and is impressed by the fact they serve their barbecue in real plates. He likes their grilled pimento cheese sandwiches and the oatmeal cookies.

At this point, he crosses the state line into South Carolina’s Midlands region, where they cook shoulders and hams. This is where the mustard comes in, and for us North Carolinians, it’s an acquired taste. This is hash and rice country.

In the Upstate and mountains, there’s no one tradition. Morris shares something you may not have heard before — the barbecue from Lexington drifted down that way, but you’ll also find ribs. One place had a Memphis-style sauce.

Morris also lists detours off major highways to major places, like Stamey’s in Greensboro, and a number of places in Lexington.

Finally, at the end are recipes, including instructions for pit cooking a whole hog. There are sauce, Brunswick stew and corn stick and hush puppy recipes, too.

And there’s a glossary and bibliography. All you need now is a tank of gas and the occasional antacid for pork overload. And hushpuppies. And slaw. And vinegar sauce.