Rowan’s population in a word: Shifting

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 22, 2015

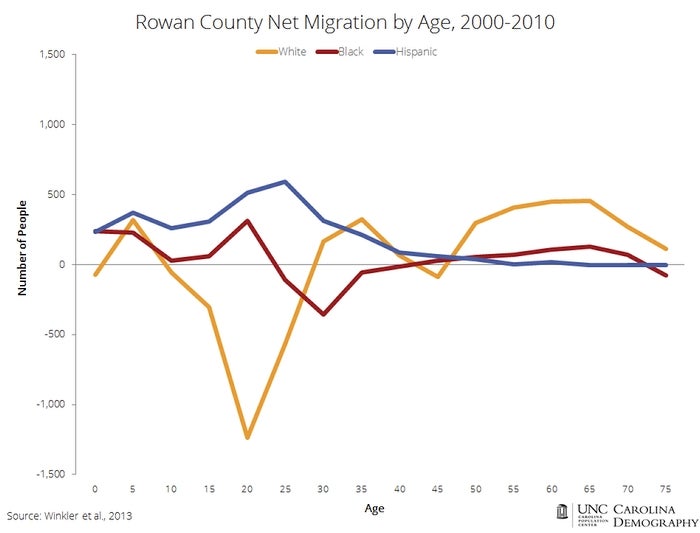

- Rowan County's net migration by age and race shows big changes for the college-age group, with whites leaving and blacks and Hispanics moving in.

Migration brings changes, especially among the young

By Elizabeth G. Cook

elizabeth.cook@salisburypost.com

North Carolina’s surge in population in the 21st century appears to have passed by Rowan County, where growth has been flat.

But a closer look at the county’s demographics shows the local population is shifting dramatically — in age and race.

So says Dr. Rebecca Tippett, director of Carolina Demography, part of the Carolina Population Center at UNC Chapel Hill.

“[T}he people moving in, that are of young ages who have children, don’t look the same as the people that are moving out,” Tippett said.

Tippett shared insights into state population trends when she spoke Tuesday at Catawba’s College Community Forum. She shared results of a statewide demographic study and broke out information specific to Salisbury and Rowan County.

Some highlights:

• Concord and Kannapolis are expected to experience steady growth, thanks to spillover from Charlotte-Mecklenburg. But Salisbury, farther away from Charlotte, is not likely to pick up as much.

• As Rowan loses young, college-age whites, it is gaining young blacks and Hispanics.

• Salisbury has become a “majority minority” city.

• Salisbury-Rowan is in a better position than many other low- to no-growth communities because of its position in an urbanized corridor.

Relative appeal

Trends in migration, the influx of new residents, can be telling, according to Tippett.

“Net migration tells about the relative appeal of a place, compared to other places,” she said.

Economically vibrant places like Charlotte and the Triangle draw people, while places that are economically depressed or have experienced natural disaster tend to lose people. Witness New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, Detroit after the recession and eastern North Carolina following Hurricane Floyd, Tippett said.

Since 1990, the state has seen net migration of 2.2 million people.

“This has been a profound change in the nature of the state and its overall population,” Tippett said.

North Carolina has always been known as a “sticky” state, she said; people born here tend to stay. In recent decades, they’ve been joined by waves of people moving in.

Came here, stayed here

Seventy percent of North Carolina’s population growth since 1990 was due to net migration — people moving into the state for college, jobs, retirement and other reasons — according to Tippett.

Before this shift, most of the state’s growth came from births outnumbering deaths, not from attracting newcomers.

But between 2000 and 2010, only Texas and Florida received more net migrants than North Carolina.

“We’re punching above our weight class,” Tippett said.

Though the Rowan region has not seen such rapid change, it also saw 70 percent of its growth between 1990 and 2010 come from net migration, she said. The broader trends shaping the state are also occurring here, but at a lesser magnitude.

Tippett asked for a show of hands of those in the small audience who were not born in North Carolina. Several hands went up.

Forty-two percent of the people living in the state in 2012 were not born here, she said. Among adults, one in two were not born here.

Tippett called this a “sea change.” Earlier figures for net migration were 30 percent in 1990, 15 percent in 1950 and 5 percent 100 years ago.

Some 58 percent of Mecklenburg’s residents were not born in the state; in Rowan County, the rate is 31 percent.

Left here and came back

Where were all these newcomers born? New York is the No. 1 state from which these residents come, but they are not always “new” residents, Tippett said.

“This is not just ‘these damned Yankees’ …,” she said. The state is seeing a reversal of the great migration of the mid-20th century, she said, when African Americans fled the South to find better opportunities and attitudes in the North.

In 1981, she said, 11 percent of North Carolina-born blacks were living in New York. Now many of those people are returning to their ancestral state, though not necessarily the town in which their parents or grandparents lived.

The other top sources of new North Carolina residents, in order, are Virginia, Mexico, South Carolina and Florida. But two-thirds of the state’s migrants are coming from other places — with every state and nation represented here now, Tippett said. That makes North Carolina a microcosm of the globe, with a diversity that is particularly evident in urban areas.

The average American moves 13 times in a lifetime, Tippett said. Top reasons for moving to North Carolina are:

• Higher education

• Job

• Moving with parents, a spouse or partner

• Attracted by some aspect of the state, such as quality of life or cost of living.

Looking at population shifts by age, Tippett said North Carolina sees a large spike in 15- to 29-year-olds, thanks to its large contingent of colleges, universities, military bases and thriving metropolitan areas.

The population growth plateaus in the 30-54 age group and then — a relatively new development — rises again as people migrate to the state for retirement.

Tippett described several migration profiles:

• College towns with a big spike in young adults — such as Boone, the home of Appalachian State University — have high turnover in that age group. That often translates into lower demand for single-family homes and greater need for such things as sidewalks, buses, bars, less-expensive restaurants and police.

• A big employment center like Mecklenburg sees a big peak in the 25-to-29-year-old age group, people moving in for a job and creating demand for higher-end rentals, night life, restaurants and entertainment. Such communities are also seeing an uptick in the 75-plus age group, which likely is people moving in to be near family and high-quality medical facilities.

• Family suburb communities adjacent to large cities — such as Union County, which has experienced spillover from Charlotte-Mecklenburg, or Johnston County near Raleigh — see a big spike in 33- to 44-year olds and children under 15. Such communities have a high demand for schools, home ownership and commuter-friendly transportation.

• Retiree havens, such as Brunswick County, have growth dominated by the 55-plus population group. They see a natural decrease, with more deaths than births. But such mobile retirees tend to be healthier and wealthier, on average, than their peers and create what Tippett called a “mailbox economy,” drawing down savings to fund their lifestyle. These communities have a high demand for arts and entertainment and less demand for Social Services.

• The youth drain profile, which is seen in counties like Halifax in the northeastern part of the state, see a big dip in population among young people who leave for college and jobs. The population is aging in place and has increased demand for Social Services and medical care.

Rowan and migration

Rowan’s migration profile by age is mixed, Tippett said. It shows a bit of the suburban profile, with an influx of young families with children.

That’s what you’d expect in a county in a metropolitan statistical area, but Rowan’s not so close that it would get a big spillover from the Charlotte urban core, she said.

According to the census, Rowan grew from 110,999 people in 1990 to 138,448 in 2010. But Cabarrus went from being less populous, with 99,590 residents in 1990, to considerably larger with 178,572 people in 2010.

Net migration from 2000 to 2010 was 4,500 people in Rowan, putting the population total around 138,448.

“Because there are not as many educational … and employment opportunities here, you see a bit of a youth drain in the 15-to-24 age,” she said. But the the drain is not nearly as dramatic as in some parts of the state, such as Halifax County.

Looking at population migration from only an age perspective can hide some trends, Tippett said.

Looking at Rowan County’s migration trends by race also, it appears the out-migration of youth is almost all white, she said.

“The almost 1,300 whites that moved out between the ages of 20 to 24 are almost entirely counterbalanced by blacks and Hispanics moving in,” Tippett said.

“So you’re definitely seeing a huge shift in the county’s overall racial ethnic composition that’s driven by migration. Because the people moving in, that are of young ages who have children, don’t look the same as the people that are moving out.”

Some of those trends are more pronounced in Salisbury, she said, which is consistent with settlement patterns statewide. In 2000, city and county populations were about 4 percent Hispanic. By 2010, Rowan’s Hispanic population was 7 percent, while Salisbury’s was 11 percent.

As of the last census, Salisbury has become a “majority minority” community, with a population that is 48.6 percent white, 37.7 percent African American, 11 percent Hispanic and the rest other.

“That has been a dramatic change,” Tippett said.

What’s in the future?

North Carolina is going to continue to grow, and to grow more diverse, Tippett said. Much of the growth experienced in the past 20 years has been fueled by Asians and Hispanics who came at young ages and have been having children. She called this the “double impact” of migrants, bringing not just themselves but also their reproductive potential.

“When the median age in the state for Hispanics is 24.7 and for whites is 42, that’s a huge fertility and mortality differential,” she said.

In 2013, the state’s adult population was 67 percent white, 21 percent black, 7 percent Hispanic and 2 percent other.

At the same time, children under the age of 18 were 54 percent white, 23 percent black, 15 percent Hispanic and 6 percent other.

Tippett said 42 percent of the state’s growth is expected to be in Wake and Mecklenburg counties. “They’ve always held the lion’s share of growth,” she said.

At the same time, one in three counties are projected to lose population, and that may be a conservative estimate, she said.

One in two counties have actually lost population since 2010, and Rowan County is one of them.

There’s some disagreement on the figures. The state demographer projects Rowan will grow by 200; the Census Bureau predicts a drop of 150. Either way, Tippett said, large changes are not expected.

“That’s essentially what you call population stability. So, relative to other areas, Rowan is definitely declining in its share of population.”

And for Rowan?

If current trends continue, how might this play out for Rowan County?

Because Salisbury-Rowan is in an interstate corridor, and situated between two of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the nation in Raleigh and Charlotte, its future may depend on positioning, Tippett said.

“Is there an opportunity to position it as, you know, small town feel but close to urban?”

It’s tough to analyze what happened to a place and why, she said, referring to areas in other states that have seen decline.

“I think there are so many positive things going on in this state that it’s possible you may be able to siphon off growth and expansion …,” she said. “We do see places in the state that struggle and will continue to struggle. I don’t know that there’s really an answer for them, because just building a road is not necessarily going to be a solution.”

Asked if Salisbury’s thriving arts community could help draw new residents, Tippett said such a factor could make a difference. She mentioned Asheville as a city where the organic arts community emerged and gained momentum.

Things can take on a life of their own, beyond what might be expected, she said. For example, Cary started out as a bedroom community, and now it’s one of the fastest-growing cities in the state with more than 100,000 residents.