Black History Month: The heroes of local integration? The children

Published 1:12 am Monday, February 9, 2015

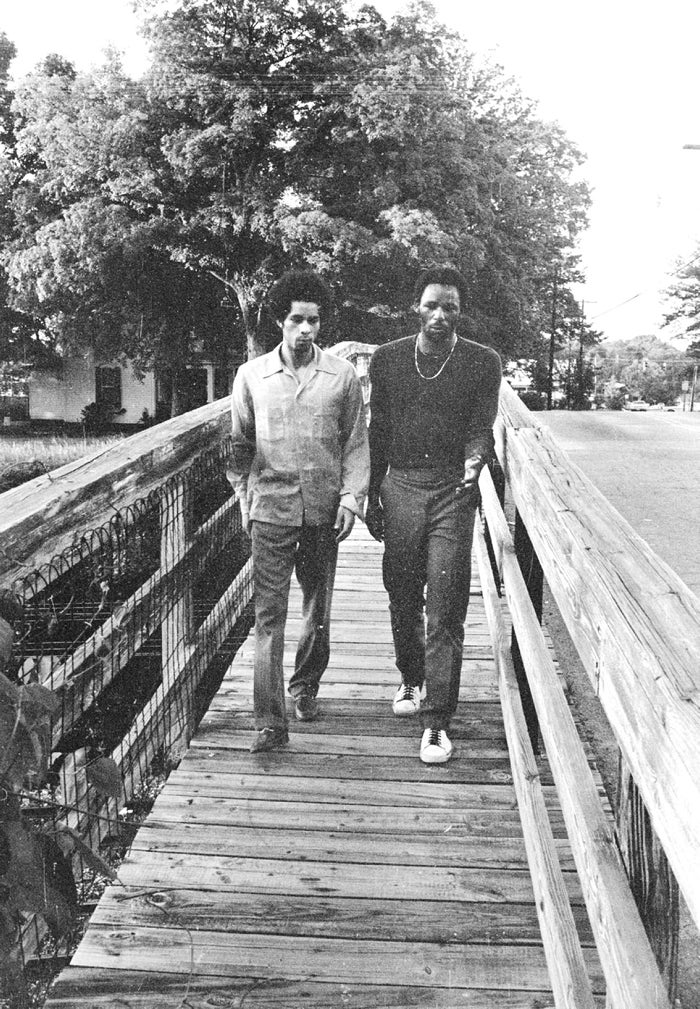

- Hodge and Richard Taylor walk across the Shober Bridge on May 16, 1979. A photo of the Taylor children appeared in the Post on Aug. 29, 1962 when they walked across Shober Bridge to Frank B. John Elementary School, making local history as the first black children to enroll in a formerly white city school. James Barringer / Salisbury Post file photo.

“… and a little child shall lead them.”

— Isaiah 11: 6

On Aug. 29, 1962, three young children led Salisbury and Rowan into the age of integrated schools.

Hodge Taylor Jr. and Ida Taylor were only third-graders — their brother Richard just a first-grader. In the Salisbury Post that afternoon was a photo of the three youngsters, along with mother Merlene and younger sister Anita, walking across the Shober Bridge on North Ellis Street to reach Frank B. John Elementary School.

The Taylor family lived “in the shadow” of Frank B. John Elementary in the city’s Jersey City neighborhood, Rose Post wrote in a 1979 article. But until then, they’d been forced to walk past the whites-only school daily, and keep walking to a school for black students on the other side of town.

That day came nearly a decade after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that having separate schools for black and white children was an inherently unequal system, and a year after Merlene Taylor — who had a bachelor’s degree in education and retired a Head Start teacher — had asked during a city school board meeting at the Frank B. John School, “Why can’t my children go here?”

Her question was the first official bid for desegregation in the Salisbury or Rowan County schools, Rose Post wrote in the 1979 article. The children’s enrolling at Frank B. John happened quietly and without incident, the Post reported at the time. And Merlene Taylor told the paper neither she nor the children thought about the fact that they were making history.

“The main thing in my mind was that the school was close enough for them to go,” Merlene told Rose Post in 1979. “I hadn’t thought about it before that meeting. … That was the first time, and I just happened to mention it.”

Whether they realized it or not, the Taylor family had made history, and opened doors. The next year, Calvin Strawder began the integration of county schools as the first black student to enroll at East Rowan High School.

Strawder’s sister, former Granite Quarry mayor Mary Ponds, said in a 2003 article that he “did not want to attend Dunbar High School in East Spencer. He wanted to go to the high school that was closest to him.”

Strawder’s experience didn’t go smoothly.

“I remember him being teased a lot, but he didn’t talk much about it. He didn’t complain,” Ponds said.

Even worse, a cross was burned on the family’s front lawn. Ponds told the newspaper the family “knew it was Ku Klux Klan” — whose grand dragon, Bob Jones, lived in Granite Quarry — and, “We knew it was because they didn’t like the fact that my brother was going to East.”

But he did go. And so did the Taylor children. They crossed a bridge. They opened doors. They broke down barriers. That’s why, this month and beyond, they should all be remembered as pioneers and heroes.