Confirming biases: Demonization of blacks has long history

Published 7:59 pm Monday, December 15, 2014

By Caryl Rivers

Los Angeles Times

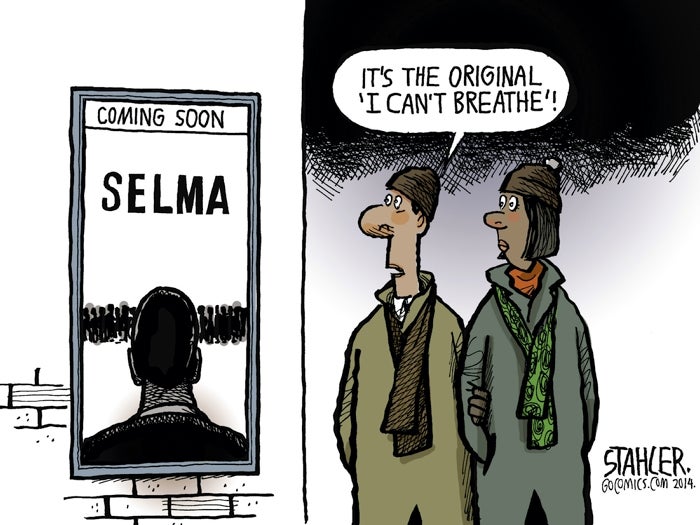

Does “confirmation bias” influence the way whites think about police shootings of young men of color?

This bias is the tendency to interpret or remember information in a way that confirms what we already believe, and helps us to ignore new data. And it may explain the tension between white cops and black kids — and the public reaction to them — more than outright racism does.

Many of us think police must be in the right because we have internalized a fear of black males and assume that they are up to no good.

As Harvard sociologist Charles Ogletree has pointed out, “Ninety-nine percent of black people don’t commit crimes, yet we see the images of back people day in, day out, and the impression is that they’re all committing crimes.”

Black men face more risk of being fatally shot than whites. Young black males in recent years were at 21 times greater risk of being shot dead by police than their white counterparts, reports ProPublica, which analyzed federal data this year.

Roger J.R. Levesque of the criminal justice department at Indiana State University says that eyewitnesses to crimes generally report scenarios that are consistent with confirmation bias. Among the studies he cites is a 2003 one in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology that found merely seeing a black face led subjects to be more likely to mistake objects for weapons.

In Ferguson, Mo., the white officer who fatally shot Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, described Brown as demon-like. Would he have used such a word if the teenager had been white?

Confirmation bias undoubtedly helped the defense in the 2013 trial in the death of Trayvon Martin. Lawyers “thuggized” the black teenager, who was walking home carrying candy and a bottle of tea when he was shot by a neighborhood watch member. Martin had no criminal record, but the defense dug up minor problems he had in school and made an animated video showing him attacking the white man who shot him. There was no actual evidence the teen started the fight. But jurors bought the narrative.

Throughout U.S. history, confirmation bias has helped some white people use the image of the evil black man for their own ends. The infamous “Willie Horton” TV ad caused a huge controversy when it ran during the 1988 presidential race between George H.W. Bush and Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis. The ad featured a fearsome-looking mug shot of a black convict who raped a woman while free under a furlough program backed by Dukakis.

Whites trying to escape punishment for their crimes sometimes find black men convenient scapegoats. In 1989, a Boston white man, Charles Stuart, blamed a “black male” when he was shot in a black neighborhood in the city, along with his pregnant wife. His wife and son, delivered prematurely, later died. News coverage was sympathetic until evidence indicated that Stuart shot his wife and himself.

In 1994, Susan Smith, a South Carolina woman, claimed that a black man had hijacked her car and kidnapped her two young sons. For nine days, the news media gave around-the-clock coverage to a search for the black carjacker. But no such man existed. Smith had drowned her sons by pushing her car into a lake with them inside.

It’s no wonder whites so easily accept the image of the evil black male. But this was not always so.

Early in the history of slavery in the Western Hemisphere, notes Audrey Smedley, professor emeritus of anthropology at Virginia Commonwealth University, blacks were not set apart from other laborers. The first slaves the English used in the Caribbean were Irish. And there were more Irish slaves in the middle of the 17th century than any others.

One 17th-century planter who wrote to trustees of his company said, “Please don’t send us any more Irishmen. Send us some Africans, because the Africans are civilized and the Irish are not.”

But plantations grew and the African slave trade exploded. To justify the cruelty of lifetime slavery, the myth had to be manufactured that blacks — especially men — were subhuman and violent. That image stuck.

In the years since, those ideas too often have intensified. As Georgetown University professor Michael Eric Dyson points out, “More than 45 years ago, the Kerner Commission concluded that we lived in two societies, one white, one black, separate and still unequal.” And we still do. If we don’t resolve this gap, Dyson writes, “We are doomed to watch the same sparks reignite, whenever and wherever injustice meets desperation.”

Only when we realize the power of confirmation bias, and start looking at reality instead of stereotypes and misinformation, will things change.

Caryl Rivers is a journalism professor at Boston University.