Rowan-Salisbury School System tackles literacy challenge

Published 12:00 am Sunday, October 5, 2014

Literacy is the new buzzword in the Rowan-Salisbury School System as it seeks to find solutions and take action to improve its below-average reading scores.

Literacy is “the foundation for learning,” said Rowan-Salisbury Superintendent Dr. Lynn Moody. “If you know how to read, you can continue to learn for the rest of your life because you can become self-directed.”

Just over half the district’s third-graders read on grade level, based on the 2013-14 end-of-grade test results.

The district bases its literacy data off of its third-graders’ reading scores from the end-of-grade test.

“Up until the third grade, you’re learning to read. After the third grade, you’re reading to learn,” Moody said.

“You can’t continue to learn without the fundamental basics of knowing how to read,” she added.

The impact of illiteracy is sobering.

Moody recently shared the following facts at the Chamber of Commerce’s Literacy Summit community forum: approximately 42 million American adults can’t read above a fourth- or fifth-grade reading level; 60 percent of inmates are illiterate; young women between the ages of 16 and 19 are six times more likely to have a child out of wedlock if they live in poverty and have below average reading skills.

During the 2013-14 school year, 52.1 percent of Rowan-Salisbury third graders read on grade level according to end-of-grade test scores. The year before, that number was 38.3 percent. In 2011-12 and 2010-11, the rates were 60.7 and 61.7, respectively.

Over the past two years, the state has implemented a number of changes, causing some of the inconstancies in test scores.

During the 2012-13 school year, a new test was implemented and districts across the board watched their reading scores plummet.

Last year, scores rose significantly — partially because teachers better understood how to teach for the test, but also because the state implemented a five-tiered scale for student achievement. Previously, a four-tiered scale was used, in which students scoring a three or four demonstrated proficiency, and those scoring a one or a two did not. Now, a three, four or five is considered a passing score.

What remains consistent, however, is that Rowan-Salisbury’s third grade reading scores are roughly 10 percentage points lower than the North Carolina average.

Moody presented a heat map at the Literacy Summit, showing how students in different areas of the county performed on their reading end-of-grade test.

The district’s 1,423 third-graders were divided into the 18 zip codes where they live. A total of 747 students showed proficiency on their end-of-grade tests, a pass-rate of 52 percent.

The highest level of achievement was found in Faith, where 83 percent of students read on grade level. Between 61 and 67 percent of students read on grade level in an area of the county out toward Mooresville, Granite Quarry, Rockwell and parts of Salisbury near the hospital and country club.

The county’s lowest reading levels were in Spencer, with 26 percent, and Gold Hill, 32 percent.

East Spencer, Richfield, Kannapolis, Woodleaf and portions of Salisbury had pass rates between 43 and 46 percent.

More than 63 percent of Rowan-Salisbury children qualify for free or reduced lunch based on their family’s income, and seven out of the 10 zip codes where 50 percent or fewer third-graders read on grade level have child poverty rates above 25 percent.

In East Spencer, where the achievement rate is 44 percent, the median income per family is $9,861 and there is a 100 percent poverty rate for children. Spencer has a child poverty rate of 45.9 percent.

“Children of poverty have fewer experiences and less vocabulary,” Moody explained. “Children take prior knowledge and hook that to new learning.”

Because of the working hours of people of poverty, their children are exposed primarily to business language.

Children of means, however, are exposed to more conversational language where they encounter questions and are asked to share their thoughts, feelings and opinions.

Poverty doesn’t just affect reading skills, though; it has financial, emotional, mental, spiritual and physical implications. Children of poverty are less likely to have strong support systems, relationships or role models. They are also more likely to be disorganized, act out and only partially complete assignments.

“Children of poverty often move frequently,” Moody said.

Those children tend to have gaps in their education because they are transient and move from school to school.

Other symptoms of poverty, such as hunger, abuse or neglect, lead to consequences that distract children from the learning process.

When Moody unveiled the district’s strategic plan in May, its top focus area was literacy.

The plan’s goal, to have 90 percent of students reading at or above grade level and for all students to achieve or exceed one year’s growth in reading each year by 2017, is lofty.

In an effort to achieve that goal, the district has implemented many changes, including a literacy framework for teaching, the one-to-one digital conversion, hiring literacy coaches, and recruiting community involvement.

The literacy framework isn’t “just about merging all of our curriculums all together,” said Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum Dr. Julie Morrow.

The literacy framework outlines the “foundational structures” necessary to “address the individual learning needs of each child,” she added.

This year, all elementary classes are required to have a literacy block each morning that’s between 90 and 120 minutes long.

The teaching skills outlined in the literacy framework include small-group guided reading and selecting reading materials based on the students’ needs.

“The components are the same across the district,” said Betty Cox, a literacy coach at Hanford Dole Elementary School.

“There is no prototype for the kid who walks in your door. You have to capitalize on their strengths,” she said. “You have to be very, very intentional. That’s what makes teaching exciting.”

Literacy coaches, like Cox, have been added this year to work on the best practices of the literacy framework with teachers.

Each of the district’s 20 elementary schools has a reading design coach. There are seven middle school and two high school literacy coaches as well. The elementary coaches focus specifically on teaching reading, while the middle and high school coaches help teachers understand how to teach reading through the other subjects they teach.

“The coaches provide our teachers with differentiated professional development,” Moody said, explaining that each teacher may need help with different aspects of teaching literacy.

Cox said the role is “multidimensional.”

“We’re catalysts for change. We’re curriculum specialists. We’re reading specialists,” she added.

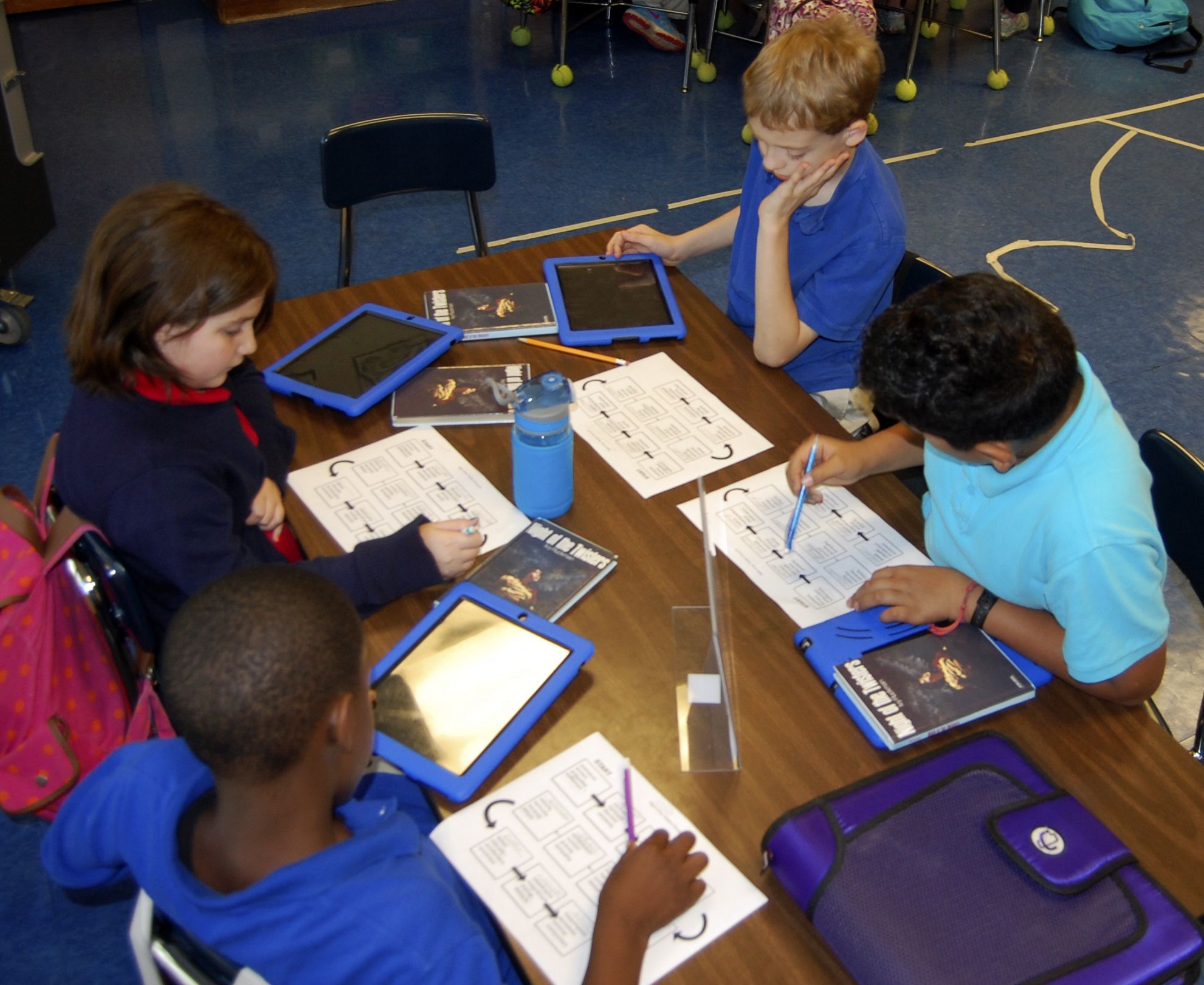

The district’s one-to-one digital conversion, which will put an iPad or laptop in the hands of every Rowan-Salisbury student in third grade or above, is a tool for literacy, Morrow said.

It allows students to extend and broaden experiences, explore and create learning. And it opens the door to all kinds of books, articles, pictures and information, she said.

“It personalizes the learning experience for children more than we’ve ever been able to personalize it before,” Morrow added.

Moody said the district provides the students with subscriptions to thousands of books, magazines and articles that can be accessed on their digital devices.

“It allows them to pick from thousands of books wherever they are,” she said. “We’re trying to give our students a lot more choices in what they’re reading.”