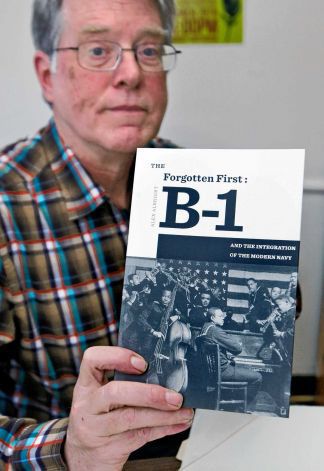

ECU professor’s book recalls all-black Navy band

Published 12:00 am Monday, February 10, 2014

GREENVILLE (AP) — Being a hero is not always about staring down the barrel of a gun.

A hero is someone who lives life with dignity and grace when circumstances encourage and expect anger and violence.

An East Carolina University professor recently published a book profiling a group of World War II veterans who lived that second form of heroism when they broke the modern Navy’s racial divide.

Alex Albright’s “The Forgotten First: B-1 and the Integration of the Modern Navy” tells the story of the men who performed in B-1, an all-black Navy band stationed at the U.S. Navy Pre-Flight School at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. They were the first black men to earn an enlisted rank. Until then, blacks only could serve as mess men and stewards, the lowest ranks in the Navy.

“They were very brave men,” Albright, an associate professor of English, said. “When you think of bravery, you associate it with front-line fighting. But bravery and courage are defined in a lot of different ways, especially in how you live your life.”

The U.S. Navy — especially in the early 20th century — had the most racist policies of the nation’s armed services. Blacks were banned from serving in the Navy after World War I until 1937 when servant positions — mess men and stewards — were open to them.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor, wanted more, Albright said.

“There was a lot of federal interest in making the South behave, to stop lynching people, to allow voting and to allow equal rights,” Albright said.

However, Roosevelt’s political capital was tied to southern Democrats so he could not take aggressive steps, he said.

With the United States’ entrance into World War II, Roosevelt’s supporters saw an opportunity for further integration.

A Naval pilot training school opened at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The late Frank Porter Graham, then the school’s president, and members of the Roosevelt administration, decided to recruit an all-black band to play at the school.

“Music was seen as non-threatening,” Albright said. However, bands had an important role in Navy culture.

Everyday activities in the Navy of World War II were carried out to music. Naval cadets were marshalled out of their barracks to band music and music was played during training marches, Albright said. It also was part of every ceremony held by the Navy.

During the course of the war, there were more than 100 black bands performing and several hundred white bands.

In early 1942, the Navy started recruiting students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College (now North Carolina A&T State University), which had a nationally recognized music program. From there, students from local high schools were recruited.

“They were both sheet music and sight players (who would play based on the conductor’s directions),” Albright said.

One of the students was Huey Lawrence, a Pittsburgh native who went to A&T to study history and play football.

Lawrence was a trumpet player who learned from Italian immigrants living in his neighborhood. He paid for his lessons by collecting bottles and turning them in for the deposit.

Lawrence did not play with the A&T band because football required so much of his time. However, he was a bugler for the school’s Army ROTC unit. When A&T band director Bernard Mason heard Lawrence, he encouraged him to enroll in music classes.

“I signed up for music and the war broke out,” the 94-year-old Lawrence said. “Word came down they were looking for an all-black band for the Navy. The music they were playing, I knew I could do that.”

Lawrence’s father served in the Army during World War I where he was gassed by German troops. Lawrence remembers his father suffering nightmares because of the experience. His parents begged him to stay in school when he told them he was enlisting.

Lawrence and others saw joining the band as a way of avoiding the draft and getting an assignment they wanted.

He said he had no idea the group was breaking a racial barrier. The band members were given enlisted men ranks, musician 1st, 2nd and 3rd.

The band went to Norfolk, Va., for basic and band training. Lawrence was appointed lead trumpet.

The band’s repertoire ranged from traditional military marches, to classical pieces, to popular jazz and black spirituals.

When they returned to Chapel Hill, the band performed during daily drills and troop reviews. They performed at war bond rallies, parties and ceremonies. Two jazz ensembles were formed out of the main band.

When the band started performing, Lawrence said you could see audiences were shocked by their mastery of classical compositions. They could not believe black musicians had the skills.

The band was popular among Chapel Hill residents, who would turn out on Franklin Street to watch them march.

The band was sent to Hawaii, which was considered an overseas assignment, toward the end of the war. The band was told early on it would not travel overseas so there was a lot of grumbling.

“Most of these guys had never been outside the state of North Carolina,” Lawrence said. “So it was quite a shock to them.”

There are multiple stories about why the band was reassigned, Albright said. It was said an admiral that favored the group brought them over.

It also was said it was hoped that bringing an all-black band to the island would reduce racial tensions involving the Navy and native Hawaiians. There were multiple fights between whites, Hawaiians and blacks, Albright said.

The band found itself under the command of a lieutenant with a reputation of treating minorities badly, Albright said.

In the book, Lawrence said the officer ran a concentration camp.

“They had shotgun guards patrolling. They had barbed wire fence up on the pretense he was protecting people from coming in, but the way it leaned in, we knew better,” Lawrence said.

The officer insulted individual B-1 members and took punitive action against the band, but everyone kept their cool, Lawrence said.

The officer once tried to apologize for hurling a racial insult at Jesse W. Arbor, one the Navy’s first black commissioned officers. Arbor pretended he had not heard the insult.

“He knew I was lying, so it hurt him worse than it hurt me because he had to live with it,” Arbor said in the book.

The band would produce records that would be played by military radio stations throughout the Pacific. Band members kept some of the records, but the officers confiscated them. Lawrence eventually reclaimed a few of the records.

“They were able to negotiate these times without trouble which was a remarkable achievement,” Albright said. “It struck me that they were able to walk away from trouble.”

Despite the treatment they received, Lawrence said he was happy with his time in Hawaii.

The band often played at military hospitals and would talk to patients afterward. Lawrence said he was moved by the appreciation the patients, many of them white Southerners, showed for the music and the time spent with them.

Within a month of Japan’s surrender members of B-1 started returning stateside for an honorable discharge. Many members returned to school while others joined bands and performed regionally and nationwide.

Lawrence returned to A&T and completed his degree while performing in numerous bands.

He was accepted to Columbia Law School in New York. However, he had met Willa Lucille Tyler, the woman who became his wife. Lawrence received an offer to teach in Ayden so the young couple moved there. He taught social studies, coached football and directed the band.

As an educator, Lawrence shared with his students the greatest lesson he learned from his wartime service.

“Give yourself a chance. You can’t judge yourself by the attitudes of people who don’t know you,” he said.

Albright said he wrote the “Forgotten First” book because he wanted today’s generation to know the people who broke through an important racial barrier.

“It came together when I started thinking the ideal audience was the grandchildren of these people,” Albright said. “Most young people know little about the tribulations of Jim Crow and segregation because their parents and grandparents didn’t want to relive the indignities of Jim Crow.”

Albright experienced this first-hand with the B-1 members.

“They talked about their service but they never talked much about the problems they endured,” he said. They were forward-looking individuals.

Albright’s work on “Forgotten First” began in 1986 when he was researching a 1947 movie “Pitch a Boogy Woogie,” a musical with an all-black cast that was filmed in Greenville. The film is shown periodically on Greenville-Pitt Public Access Television, channel 23 on Suddenlink cable.

Lawrence was a member of the movie’s band. Albright struck up a friendship with him and met other members of the film’s band, many who lived in eastern North Carolina.

“I kept hearing from the group that they were the first blacks to serve above the gallery rank (in the Navy),” Albright said. The more they talked about their experience, the more he realized there was a bigger story to be told.

While the B-1 members received a commemorative plaque in 1992 to mark the 50th anniversary of the band’s formation, the U.S. Navy did not recognize them as the group that integrated the Navy.

That recognition went to band members who were trained and stationed at the Great Lakes naval stations beginning in June 1942.

Albright had documentation that showed B-1 members enlisted several months before June 1942. However, he could not find any documentation showing when B-1 was formed. The Navy had boxed up and stored its records from the time but they were not catalogued.

About seven years ago, Albright went to the National Archives in College Park, Md., to continue his research. An archivist knew where the boxes from that period were stored and offered to search them for Albright.

It took some time but the archivist brought out a box. It contained a letter that said the Navy needed a “colored” band to perform at the Chapel Hill pilot’s school. The letter documented the arrangements needed to bring the musicians to Chapel Hill and to house them. The letter proved B-1 had been formed in March and April of 1942, two months before Great Lakes.

“It was pretty exciting to see that letter, to know it verified their story,” he said.

The Navy now recognizes the members of B-1 as the ones who integrated its ranks.