Sports obituary: Kesler had amazing day — amazing life

Published 12:01 am Thursday, March 30, 2023

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

RALEIGH —”Salisburian Re-writes School Rushing Record” was Post sports editor Horace Billings’ headline in the Sunday newspaper that was tossed by carriers into front yards on Nov. 22, 1964.

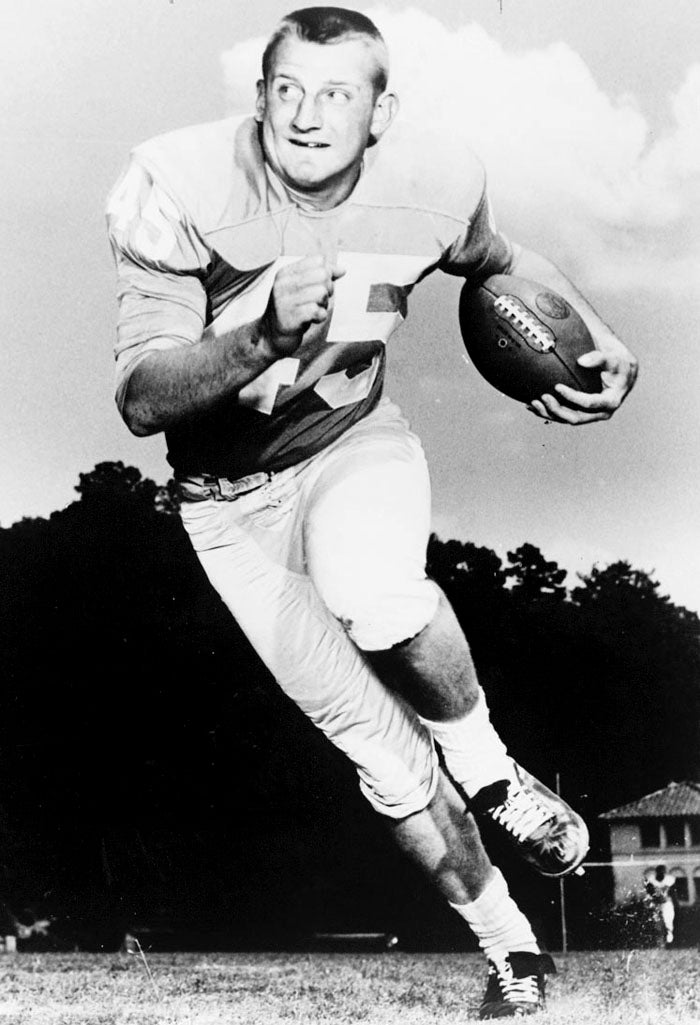

That “Salisburian” was Eddie Kesler, who spent the bulk of his college career as the lead blocker for UNC star Ken Willard.

On that auspicious day in 1964, Kesler got a career-high 19 carries in the final game of his college career against arch-rival Duke. He made each of them count for 172 yards.

Kesler scored a touchdown against the Blue Devils in a 21-15 victory in front of 45,000 screaming fans at Kenan Stadium. He rumbled 63 yards from the UNC 31 to the Duke 6 before he was caught from behind to set up Willard for another TD.

When the dust settled, Kesler had broken an immortal UNC single-game rushing record set by Charlie “Choo Choo” Justice in 1946, and Kesler and Willard had become the first backs in Tar Heel history to rush for more than 100 yards in the same game. Willard, who would become the second pick of the first round of the 1965 NFL draft and a perennial All-Pro for the San Francisco 49ers, ran for 107 yards.

“Duke’s defense was really spread out, so Willard and I lined up as split backs and I got a lot more carries than usual,” Kesler told the Post in an interview a dozen years ago. “For one day, we were both running backs.”

Ralph Edward Kesler Jr. died peacefully on Sunday in Raleigh at 81. That football outing against the Blue Devils etched his name permanently in the lore of UNC athletics, but that rugged performance was just a fragment of an amazing life.

Athletically, he was special, in basketball and baseball, as well as football. Those who got a chance to know him, those who served with him in Vietnam, those who worked with him in Raleigh, will tell you that he was an even better man than a ballplayer.

The son of “Poss” Kesler, police captain and former football hero, Eddie Kesler became a standout athlete at Salisbury’s Boyden High.

He scored 1,210 points in basketball, a school record at the time. He scored 35 in game against Gastonia. He averaged 19.1 points per game as an All-State senior in 1960 for a team that averaged 50.

As a baseball first baseman for Boyden and Salisbury American Legion, Kesler showed enough power to attract the attention of pro scouts, but his father wanted him to go to college and football was a sport in which he was being inundated with scholarship offers.

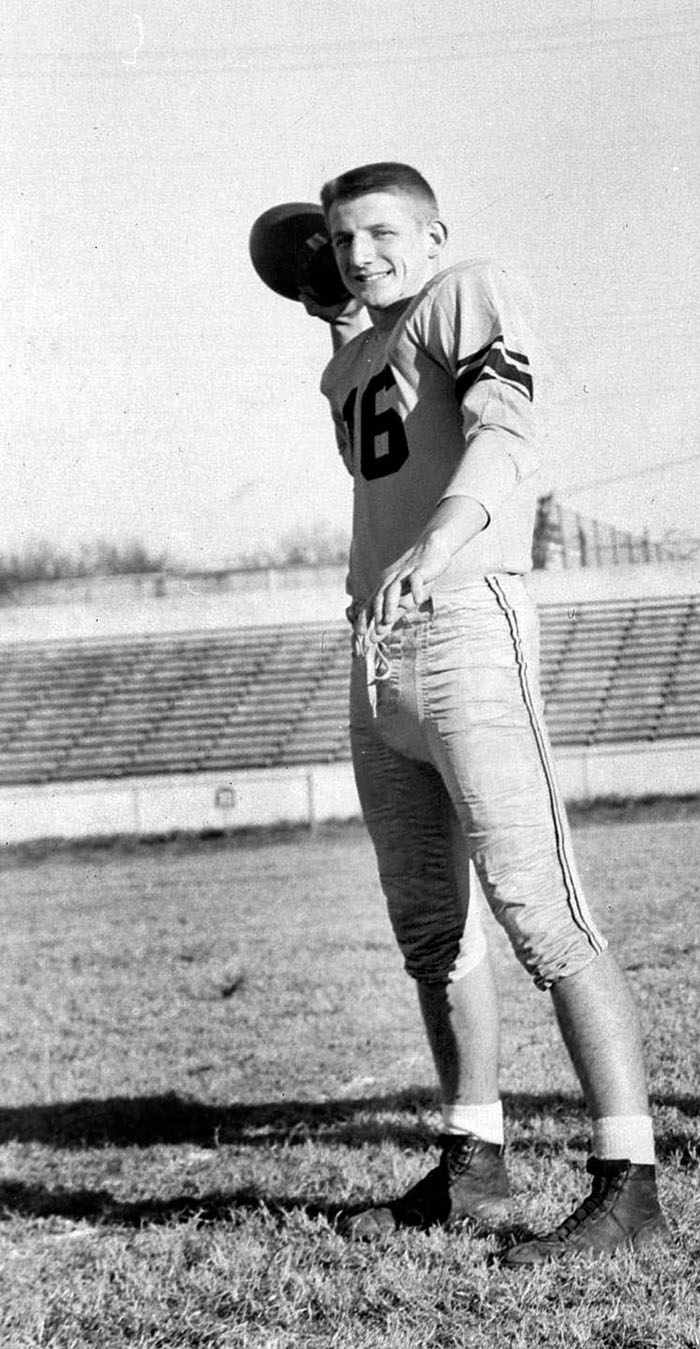

Playing tailback in coach Bill Ludwig’s single-wing offense in which the ball was snapped to either the tailback or fullback, Kesler helped win the 3A state title in 1957 as a 15-year-old sophomore. He had hands the size of fruit baskets and a strong arm, and opponents had a difficult time figuring out what he was going to do with the ball.

The 3A ranks were the largest classification then. Boyden lost once during that championship season — to the Wilmington team led by Roman Gabriel.

Playing in standing water and in miserable weather conditions at home, Boyden outplayed Fayetteville 21-0 to take the state championship. Fast but small, Fayetteville had upset Wilmington to win the Eastern Conference, but was overwhelmed by Boyden’s power.

“That game was all about the rain and the cold,” said Kesler, who also played in the defensive backfield. “Both teams had offenses that were kind of 3 yards and a cloud of dust, and that night, it was 3 yards and a cloud of mud. The difference was our wingback Bobby Crouch on reverses. Our fullback (George Knox) took the snap, faked it to me, then gave it to Crouch coming around. On that field, once a defender took a step in the wrong direction, it was over.”

As a junior, Kesler made All-State.

As a senior he was All-State and All-America. He accounted for 14 of the 18 touchdowns Boyden scored. He rushed for 912 yards and passed for 762, eye-popping figures for that era.

Kesler’s 4,199 yards of career total offense would last as the school record for Boyden and Salisbury for 50 years. John Knox, who directed Salisbury’s 2010 2AA state champions, finally broke it.

Kesler captained North Carolina’s 1959 Shrine Bowl team and ran back an interception for a touchdown. He captained the West squad in the East-West All-Star Game in the summer of 1960, played both ways and stood out both ways in a 13-6 struggle. He was voted MVP.

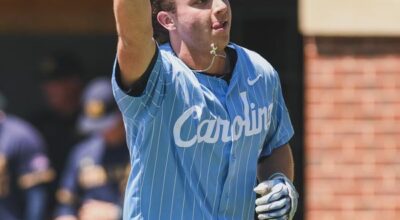

In April 1960, Kesler signed with UNC. Head football coach Jim Hickey came to Salisbury for that monumental event and brought two assistants along.

Hickey believed in the power running game out of the Wing-T formation. By the time Kesler and Willard were sophomores in the 1962 season, UNC’s staff had figured out that two of their best players were 215-pound fullbacks — Willard and Kesler — and they needed to get both on the field. They made Willard, the faster of the two, the halfback and primary ballcarrier, with Kesler leading the blocking for him as the fullback.

It worked out well enough that Willard rushed for more than 2,000 yards as a Tar Heel. Kesler got enough carries to gain 157 yards as a sophomore, 314 as a junior and with the aid of that monstrous game against Duke, 465 as a senior — a total of 936.

In 1963, UNC experienced its greatest football success since the Justice days, 9-2 and co-champions of the ACC. The ninth win was a 35-0 annihilation of Air Force in the Gator Bowl, marking the first time the Tar Heels ever won a bowl game. On UNC’s first offensive snap, Kesler sent an Air Force defender flying, springing Willard for a big gain. Kesler scored a TD in that game, the one that made it 28-0.

Kesler’s reward for all those unselfish blocks came when he received the Jacobs Trophy for 1964 as the ACC’s best blocker. That was normally an award given to a lineman, but Kesler had made an impact on voters as well as opposing linebackers.

Kesler’s most prominent physical feature other than enormous hands was a nose that was frequently broken by opponents’ elbows and knees. He broke it three times during the 1963 football season — against Virginia, against Michigan State, and then in the Gator Bowl.

All told, he broke his nose 10 times during his playing career. He broke his collarbone twice. There also was one broken arm. No big deal. As a lead blocker, pain is part of the job description.

Kesler was drafted by the NFL’s Pittsburgh Steelers, who planned to try him as a linebacker, and by the American Football League’s Houston Oilers.

He picked the Steelers and got a respectable signing bonus.

Before reporting to the Steelers, he spent 15 days in a hospital after extensive surgery to repair his nose. He wasn’t 100 percent when he reported, but he had good scrimmages and made cuts before his breathing issues resurfaced. He only played in one preseason game.

His last fling with football was with the minor league Charlotte Vikings, who competed in the Southern Football League. He suited up for Charlotte in 1965, where his teammates included former UNC guard Clint Eudy and former Livingstone fullback Rudy Abrams, who would later coach the Blue Bears.

After football came the Marine Corps. As a college graduate, he entered the Corps as a supply officer, but all Marines receive combat training, and he headed for Vietnam as a 25-year-old lieutenant in July 1967.

“I’m in the logistics end,” Kesler told the Post shortly before he headed overseas. “But that doesn’t mean I’ll be doing that in Vietnam. A Marine is trained for all types of duty. A Marine’s basic training is in the infantry.”

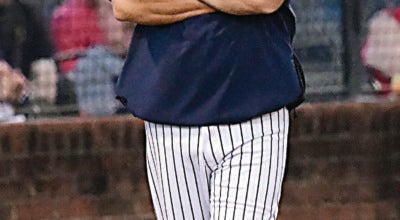

He made it back from the war and worked as a football coach for the Marines football team based at Quantico, Va. He was discharged as a captain in 1973.

He had successful careers in real estate and construction.

While Kesler supported many organizations over the years, the Marine Corps made a lasting impression. He helped found Back Home Boxes, a non-profit organization dedicated to sending care packages to servicemen serving in Iraq and Afghanistan.

For more than 10 years, he served as Deputy Sergeant at Arms in the North Carolina Senate. He never met a stranger and had a delightful sense of humor. Many have said that the white-haired former athlete with the finger-crushing handshake was the most popular fellow on the floor of the senate.

Kesler was inducted into the Salisbury-Rowan County Sports Hall of Fame in 2006.

He is survived by wife, Patricia, whom he married in Raleigh in 1981, a daughter and two grandchildren.

Services are planned for Friday in Raleigh.