Switch-hitting isn’t just for baseball

Published 12:10 am Saturday, March 18, 2023

SALISBURY — For many artists, the idea of changing the hand they paint with is nearly unfathomable. But for Gordon Furr, changing hands was not only life changing, but in some ways, life saving.

Furr has lived on his family’s property on Stokes Ferry Road most of his life, and he has been an artist for just about as long, though he only began publicly identifying himself as an artist recently. Initially, he did pencil drawings and worked with water colors, and he used his right hand.

But in 2006, after initially realizing he was dragging his right foot and his endurance had dropped off precipitously, he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. And by 2008, he could no longer hold a pencil or paint brush in his right hand, and he thought his artist days were over.

“In 2008, I gave up,” he said. “I just believed I could no longer do it.”

He was approved for disability after a bit of a wrangle, and so stepped away from years of work in the home building world, where he’d designed mobile homes and manufactured homes then worked for a manufactured wood/flooring company. It was a challenging time, paying the bills and taking care of his small family, and he ended up selling parts of his family’s land, but he managed.

And through the years, he continued to feel the pull of his art, the art he thought he would never again create.

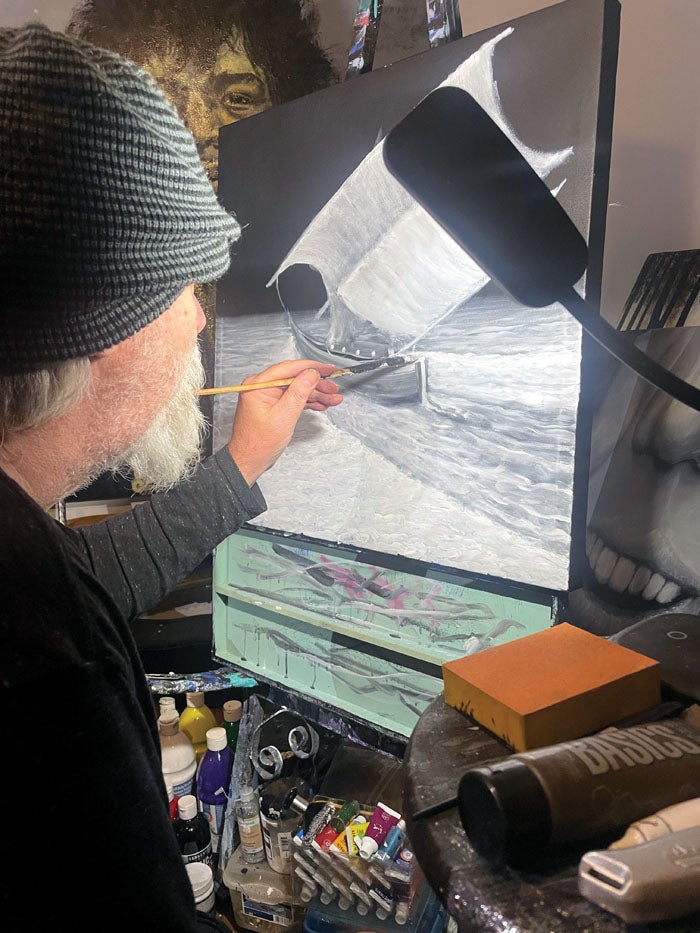

“By 2018, I was so driven by the desire to paint that I decided I had to become an artist, whatever it took. I decided to try working with my left hand,” Furr said. “I didn’t think it would work. I really didn’t. But I was so pushed to do something that I picked up a brush.” Initially, he didn’t even create brush strokes, but used dots to create the images, using oil and acrylic paint this time around.

And what he discovered was that in using his left hand, “I was engaging the other side of my brain, and suddenly my art began to have life. The work I had done with my right hand was technically proficient, but it was flat, dull. What I began to create with my left hand was completely different from what I had created before, and I was blown away by it.”

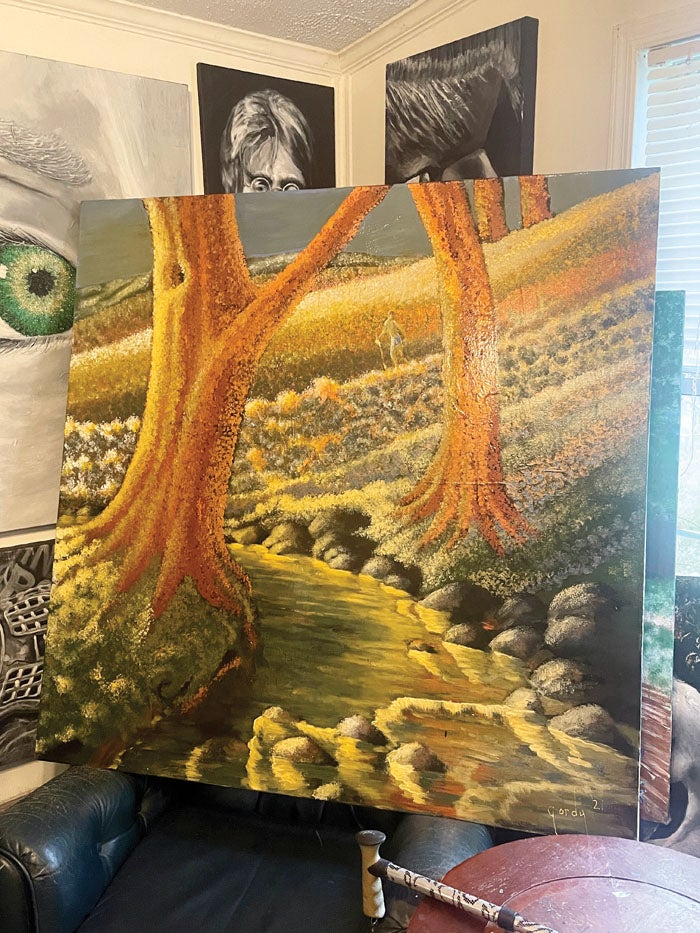

His newer creations are often large canvases because while he did eventually learn to use brush strokes, he still needs to use larger strokes. And the work is still technically proficient, but now has somewhat ethereal qualities.

He has done portraits, and the facial details, which can sometimes be difficult to capture, are near perfect representations. A larger-than-life portrait of his son, Kelse (known to friends as Spencer), on his wedding day, captures his son’s image like a mirror, and the affection shines through.

But it is the art Furr creates from his imagination or his memory that nearly vibrates at times with emotion. A painting of the woods where he grew up, with a subtle representation of himself and his dog running through the trees, sings with the joy of his childhood love of those woods.

“I’m documenting those I love, and my life,” Furr said. “I’ve lived a really good life, growing up here and running all over the place as a child. Lightning bugs were our streetlights. I spent days in these woods, and I loved every minute of it.”

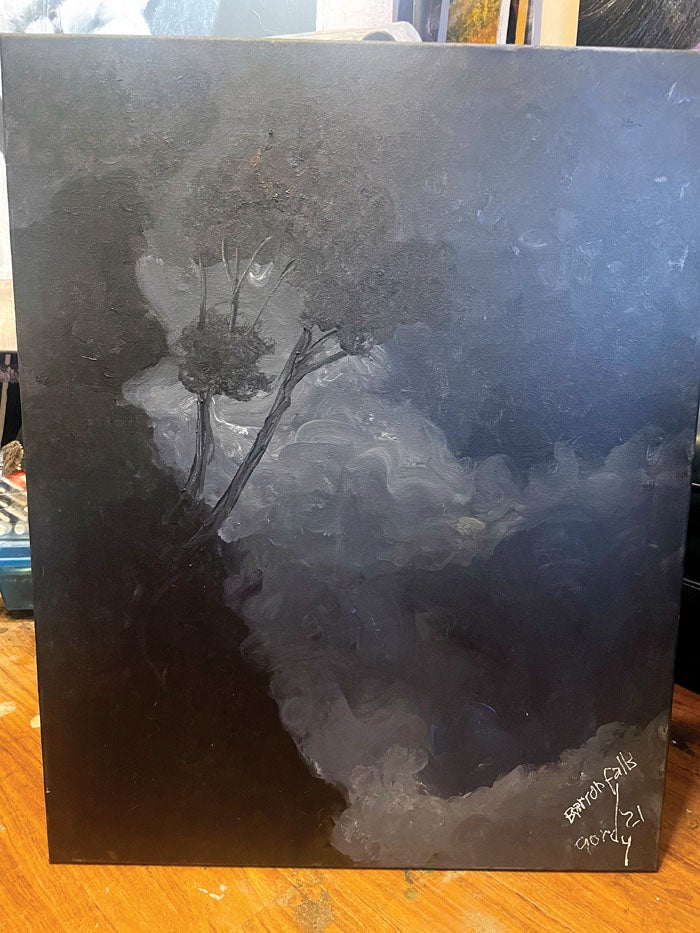

Those memories are part of the world he recreates in his art, alongside places that speak to him, including Barron Falls, Australia, which in the wet season is a massive waterfall in a national park. The painting of the falls is in shades of black, gray and white, and though subtle, Furr manages to capture the movement and the majesty of the falls with those few colors.

He also paints mythical figures, like the goddess Sophia, who while not a typical Greek goddess, does represent wisdom in Christianity and other religious cultures.

“Every year I paint another Sophia,” said Furr.

There are other portraits, also on a grand scale, of artists like Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, stacked in his back-room studio that was once his son’s bedroom. On top of an armoire, there is a pencil drawing of his grandfather and father, and on the floor is a self-portrait, but the works are different. The two upper portraits are smaller, and were done with his right hand. The lower self-portrait is larger, and made of broader strokes, and was done with his left hand. All three are fantastic representations, but the difference in the style is palpable.

Furr’s wife, Tonia, and his son have both been supporters of Furr’s art all along, and Kelse has his own artistic abilities. He has found motivation in watching his father make such a drastic change.

“It’s a good inspiration, seeing him learn to use the other side of his body,” said Kelse. “I know how physically and mentally challenging it has been. I’m very proud of him. I mean, how many kids can say ‘my dad’s an artist?'”

And the MS, while progressing, is not holding Furr back. In fact, he credits it with saving him by forcing him to come at his work from a different perspective and by allowing him to focus on the art.

“If I didn’t have MS, I would still be working away at a job and not focusing on my art, and I wouldn’t have reached this point,” he said. “The truth is, my life has been completely different since 2008, and I’m grateful for it. I know people will think I’m just saying that, but I really mean it. I don’t know how much time I’ve got, the lesion has not spread as of yet, but you never know. So I am trying to make sure I make the most of my time.”

Furr can paint, often standing for larger canvasses, for about 10 minutes before needing a break, but he does work steadily. In addition, he has taken up writing a short story that he posts, in real time as he writes, on his Facebook page. He is also creating what he deems simple art pieces to go with the story.

Furr has not had any type of showing of his art, though he has sold a number of pieces on social media, but that may be about to change. He is in discussions with Tiffany Day, the owner of Shug’s at Brooklyn South Square about having a show — or two — there, likely in May. The pieces will be available for purchase, but Furr admits some may be hard to part with.

“They are so much a part of me, so important to me, that a few I may not be able to part with,” he said. He does want to be sure to record them all in some fashion before they leave him.

“For many, many years I didn’t call myself an artist,” Furr said. “I didn’t think I merited that.” Now, he does, and the feedback he has gotten across the board has been positive.”It warms my heart” when he hears that others appreciate his work, and he is excited to think his paintings will be hanging, and loved, in other homes.

“Can I say it’s a dream come true?” he said, smiling. “I can’t wait to see where this chapter takes me.”