Darryl Strawberry: Big man with a big message

Published 12:00 am Sunday, May 30, 2021

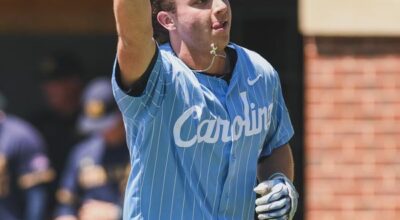

- Former Major League Baseball player Darryl Strawberry speaks to veterans and JROTC students at an earlier Vietnam Veterans Commemorative Event. Allison Lee Isley/Salisbury Post File Photo

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — At 6-foot-6, his shaved head gleaming, Darryl Eugene Strawberry isn’t your run-of-the-mill ordained minister.

The servers at the downtown Salisbury restaurant, The Smoke Pit, hadn’t been born yet when Strawberry was leg-kicking and upper-cutting his way to massive home-run seasons for the New York Mets. L.A. Dodgers and New York Yankees, but they know something special is up. They can sense the excitement in the air as Strawberry enters the diner. His name was magical once. Heads swivel. Kids and grown-ups alike migrate toward his larger-than-life presence for photo ops.

A fellow with a New York accent looks like he might have a stroke. He claims he was there the day Strawberry launched three home runs. He doesn’t say if it was against the Cubs or the White Sox. Both of MLB’s Chicago clubs were on the receiving end of three-homer assaults by Strawberry. They came 11 years apart, almost to the day, so the tall guy had some staying power.

Strawberry, who lives now in St. Louis, came to town as part of the speaking team for “Game Plan For Life,” a group headed by Terry Osborne of the Rowan-Kannapolis ABC Board. You’ve heard the radio ads on WSAT: “Preparation for the game of life does not require the practice of underage drinking.”

Strawberry, 59, has been speaking to several levels of young people — from middle schoolers to college students. He addressed Catawba baseball players before they headed to the regional in Greenville, S.C.

Martin Alphonso “Al” Wood, the former UNC basketball sharpshooter, is a veteran speaker for Osborne and is also seated at the extra-long lunch table with Strawberry. Wood is also 6-foot-6, but he’s a more familiar sight in Salisbury and his presence causes less fuss.

Wood, 62, has stories, though. He shares them between bites of pork, greens and cornbread and sips of sweet tea.

He’s orginally from Gray, Ga., 20 minutes from Macon, but he was spending time at Gardner-Webb in the summer of 1976 when he became fascinated with the Olympics. There were four UNC players on the Olympic hoops team (Dean Smith was head coach), so Wood decided he wanted to go to UNC.

“I didn’t know any better — I thought Dean Smith coached the basketball team every Olympics,” Wood said. “So I wrote him a letter. I told him he should come watch me play. It didn’t occur to me that there were probably 500 other kids writing that same letter to him. Recruiting was different then.”

Smith didn’t go down to Georgia, but he did send assistant coach Eddie Fogler, who watched wide-eyed as Wood poured in 58 points in a championship game.

UNC made an offer. Wood didn’t accept right away.

“I still wanted to visit Alabama because I wanted to meet Bear Bryant and still wanted to visit UCLA so I could meet John Wooden,” Wood said.

Eventually he did join the Tar Heels and was super for them — more than 2,000 points, fifth on the all-time scoring list. He’s ahead of Charlie Scott, Michael Jordan and Walter Davis, among others. Not many people would guess that, but Wood was awfully consistent. He’d get 19 every night.

Sadly, Wood was selected for the 1980 Olympic team, his dream, but that was the summer the USA boycotted the Moscow Olympics.

If Wood was born to knock down mid-range jumpers, Strawberry was born to bash baseballs.

Growing up in Los Angeles, he lived a few blocks from the equally talented Eric Davis. They were best buddies and were teammates on summer league teams.

Davis was getting Division I basketball offers, which pried some of his attention away from the diamond, but Strawberry was focused on a baseball future.

“We had role models from L.A., guys who had made it big in baseball — Eddie Murray, Ozzie Smith, Hubie Brooks,” Strawberry said.

Strawberry was viewed by scouts as a generational talent with ungodly left-handed power, augmented by excellent speed and arm strength. Davis was a jet, even faster, but he was right-handed and smaller.

The Mets grabbed Strawberry with the first pick of the 1980 draft. Davis lasted on the draft board until the Cincinnati Reds took him in the eighth round with pick No. 201.

“People saw me as the kid who had everything, the guy who had it made,” Strawberry said. “But I was already badly broken inside. My dad was a raging alcoholic and he’d beaten the heck out of us. My mom was raising five kids by herself.”

While he appeared to be Superman and to have Cooperstown already stamped across his chest, Strawberry didn’t succeed overnight. There were struggles in the minor leagues at Kingsport and Lynchburg.

“I wasn’t far from quitting, was starting to question if baseball was what I really wanted to do,” Strawberry said. “But then in 1982 it came together for me when I was playing for Jackson, Mississippi, in the Texas League.

Strawberry played in a pitcher’s park, with thick air and deep power alleys, but he hit .283 with 34 homers and 97 RBIs. That’s the year he turned the corner, but success was a double-edged sword. Now he was looked at as the savior for a struggling franchise. With great potential, comes great expectations.

When he arrived in New York as a member of the Mets, a month into the 1983 season, he was joining an awful club. The Mets were a dismal 68-94 that season, but the 21-year-old Strawberry offered hope. He mashed 26 homers and was National League Rookie of the Year.

The Mets acquired Keith Hernandez to play first base not long after Strawberry was promoted from the minors. By 1984, with a young pitching staff led by Dwight Gooden and Ron Darling, the Mets were a second-place team.

They acquired all-star catcher Gary Carter to handle that young staff in 1985, and the Mets were World Champs in 1986. Strawberry belted a pair of clutch, game-tying homers in the NL championship series with Houston — one of them off Nolan Ryan — to help propel the Mets to the World Series.

In 1986, Strawberry was only 24 years old, and while it seemed he was on the top of the world, he really felt like the weight of the world was perched on his shoulders.

“Playing baseball — that was the easy part for me,” Strawberry said. “But then life shows up. The pressure of living in fast-paced New York at such a young age was difficult. From the time I was 21, I was drinking and drugging, and I just started to fall deeper and deeper into it.”

Still, in the 1980s, his physical gifts were so strong that there weren’t many better players. He was an all-star eight straight seasons from 1984-91. He definitely could have been the league MVP in 1988 when he finished second in the voting or in 1990 when he was third.

In November 1990, he escaped the Big Apple. He headed back home after signing a $20 million free-agent deal with the Dodgers.

He produced one mighty season for the Dodgers in 1991, but the battles with his inner demons were taking a toll. There were suspensions and injuries and a steep decline in the games in which he was able to play, as well as a drop in his production when he did get on the field.

Davis joined Strawberry with the Dodgers in 1992, but injuries had diminished him by that point. Davis had stolen 80 bases in 1986 and had combined 37 homers with 50 steals in 1987, but he played flat-out and he’d run into too many walls by 1992.

Strawberry’s mother died in 1995, an event he views as one of the lowest points of his life.

But Strawberry’s downward baseball spiral would be resurrected by the Yankees and manager Joe Torre.

Strawberry smacked 24 homers for the Bronx Bombers in 1998. He was often the DH for a 114-48 machine that was 11-2 in the postseason and swept San Diego in the World Series.

Strawberry’s last MLB homers and RBIs came as a 37-year-old for another World Champion Yankees team in 1999.

“They were the Yankees, and they could have picked anyone, but they picked me,” Strawberry said. “I’ll always be grateful to Joe Torre. I was able to go out as a champion.”

The years have been eventful. He’s survived two cancer battles.

He finally whipped his addictions or at least learned to cope with them.

“Nineteen years ago is when I got on the road to recovery,” Strawberry said. “Credit my wife (Tracy). She beat on doors and pulled me out of drug houses. She led me to the church and to the Lord.”

Since then, he’s learned to turn all the mess into a message.

He was shy giving his testimony in front of crowds at first, but each year, he’s become a more confident, more determined, more powerful speaker.

“Darryl has a real depth of conviction now through his strong faith,” said George McGovern, who has been chaplain to the Yankees, Mets and the NFL’s New York Jets and Giants. “He has a gift for speaking and he speaks from the heart and from experience. When Darryl speaks, it isn’t theoretical, it’s real. He’s lived it.”

His message for students is to say no to all the tempatations that are out there.

“There’s an epidemic sweeping this country and destroying so many or our young people,” Strawberry said. “It starts simply with smoking weed, but then when that’s not enough, you’re going to try something else. I know how it goes. Next thing you know you’re headed down a deep, dark tunnel.”

Strawberry is in the New York Mets Hall of Fame.

It’s unlikely he’ll make the big one in Cooperstown, as his numbers declined sharply when he reached his 30s. Still, he socked 335 homers, drove in an even 1,000 runs and stole 221 bases. Even if he’d been named Darryl Smith or Darryl Jones, he would’ve been a magnificent, memorable athlete at his peak.

Because he was so gifted, he’s doomed to always be a cautionary tale, but he says he has zero baseball regrets. He never loses a minute of sleep worrying about what might have been.

That’s because he knows his mother would be proud of the man he is today.

“My mom was never worried about how well I was doing in baseball,” Strawberry said. “All she ever wanted was for me to be a good man, and I’m a much better man now than I was 20 years ago. After I talk to a group of students, I feel good. I don’t talk about numbers or stats. I talk about real life. They’ll remember what I had to say.”