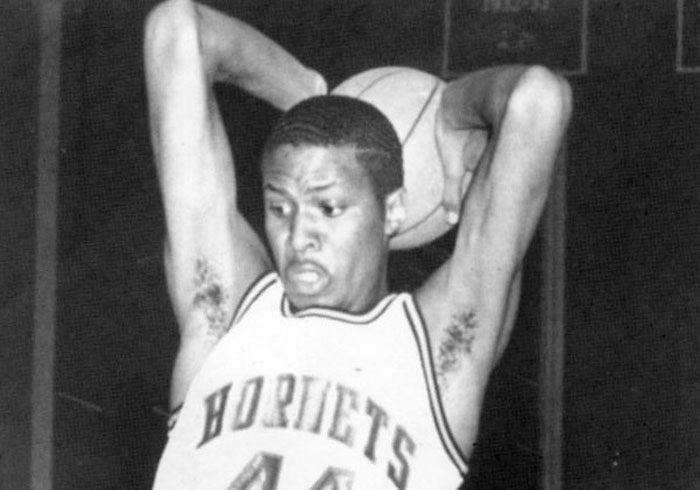

Legends: In the Big East, Campbell made his mark with defense

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 5, 2020

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — It was the first round of the 1991 NIT.

The James Madison Dukes, thrilled to be in the tournament under fiery coach Lefty Driesell and led by Maryland transfer Steve Hood, faced the Providence Friars, broken-hearted to be in the tournament because they had beaten six ranked teams, including Big East squads UConn, Georgetown, Syracuse and St. John’s, and expected to get an NCAA bid.

For a proud Big East program in those days, NIT was shorthand for Not In Tournament.

JMU had the emotional advantage and took it to coach Rick Barnes’ Providence team for a while. Hood had 15 points in the scorebook by halftime. James Madison led by five.

The tide turned in the second half after Barnes put defensive stopper Fred Campbell on Hood. Hood would finish with 27 points, but he shot 2-for-10 from the field in the second half.

Providence won in two overtimes.

Campbell, a Salisbury native who turned 50 a few months ago, made a similar impact in many Providence games during the 1990-91 season. A prolific scorer at Salisbury High and in junior college, he became a defender/rebounder in the Big East for Barnes. At Providence, he accounted for more rebounds than points. He scored only two points in that JMU game — on a stickback in overtime.

“If you wanted to play for Rick Barnes, you had to accept a role,” Campbell said. “Mine was defense first and rebounding second.”

In the second round of the 1991 NIT, Campbell turned in one of the stoutest games of his career— 10 points and 10 rebounds in an 85-79 victory against West Virginia. But the Friars’ season ended with a third-round loss to an Oklahoma squad that would reach the championship game.

Campbell was honored after that season with Providence’s “Unsung Hero Award.”

It all started for Campbell in Salisbury. He was a kid who had a desire to be great but still had an awfully long way to go.

“Growing up in Salisbury (late 1970s, early 1980s), I was fortunate,” Campbell said. “There were guys like Floyd Kerr, Charles McGee and George Miller, who would take a young guy under their wings. If you had parents who worked, they knew they could trust those men to look after you. They taught us sports. They pushed us. They also taught us respect and they taught us to do the right things. Floyd Kerr, everyone called him Pee Wee, gave me my first summer job when I was 15, and I worked with him every summer for the next 17 years. I had a key to Hall Gym when I was 15.”

In his elementary school days, it looked Campbell might become a baseball pitcher.

When he reached seventh grade at Knox Junior High, baseball still looked like his best option for future stardom. He had a coach at Knox who was instrumental in his rise — Bill Cansler.

“I rode the bench in basketball at Knox in the seventh grade and even in the eighth grade,” Campbell said. “But Coach Cansler kept telling me that I had a lot of talent, that I was going to be one of those late-bloomers if I’d just keep working at it.”

Campbell remembers his class was the second group of ninth-graders to attend Salisbury High. He was 6-foot-4 then, but when he returned from the summer vacation between his freshman and sophomore years, he had sprouted to 6-foot-8.

“That changed a lot for me as far as confidence,” Campbell said. “Things started to click.”

As a sophomore in 1985-86, Campbell sat on the varsity bench for a few games, then went down to the jayvees. In January, his talented classmate Donald Jenkins was lost for the season, and Campbell was called up to the varsity. This time Campbell was ready to help Coach Sam Gealy’s squad. North Rowan had a fantastic, senior-laden team (Antione Sifford, Jimmy Kesler, Ralph Kitley) that was headed for a 2A state title, but Campbell scored 20 against the Cavaliers in a close loss. He scored 20 more in the Central Carolina Tournament championship game setback against North that ended Salisbury’s season.

“Those games against those North Rowan seniors were important for our development,” Campbell said. “We grew up as sophomores. We got valuable experience. We could see what it took to be champions. We also had a senior on our team, Greg Mashore, who was one of the most underrated players who ever played in the county. He taught us a lot.”

In 1986-87, the Hornets were unstoppable with a core group of talented, experienced juniors — Campbell, Jenkins, Bryan Withers, now the Salisbury High coach, and Warren Alexander, who was a terrific three-sport athlete.

Withers, Campbell and Jenkins averaged double figures. Salisbury went 30-2. The only losses were to 4A East Meck in the finals of the Christmas tournament at Catawba College and late in the regular season to CCC rival Lexington. Salisbury went 15-1 in the CCC, and the CCC was loaded. The Hornets went 9-0 in the postseason, capping the year by crushing Farmville Central 63-45 in the 2A state title game. Campbell scored 22, while Withers had 20 in the final.

Withers was Rowan County Player of the Year. Campbell, who racked up several awards during Salisbury’s postseason run, was first team all-county.

The 1987-88 season was bittersweet for Campbell. Individually, it was his finest season. He averaged 17.8 points and 9.8 rebounds and was Rowan County Player of the Year and Central Carolina Conference Player of the Year. He was the 2A State Player of the Year. He played in the East-West All-Star Game. He had a 32-point game to beat a great Lexington team and topped 20 points 12 times. He scored 568 points as a senior.

But Salisbury couldn’t repeat its state-title run, despite being a year older and despite going 30-2 again with 16 straight CCC wins. Both losses came in the postseason. Both were against rival Lexington, including a season-ender in the Western Regional final in Hickory. Lexington went on to win the state championship.

“We should’ve won it all again my senior year, but I can’t take anything away from Lexington,” Campbell said. “Lexington was deep and matched up with us perfectly. When Lexington won the 2A championship, it was the third straight season a CCC won it, and that tells you how good our league was. Why it didn’t work out for us as seniors, I don’t know. Maybe we weren’t as focused. Maybe we didn’t play together quite as well. Everyone was getting college offers, getting ready to go their separate ways, so it was harder to maintain that tight bond we had when we were younger.”

Campbell had gotten good exposure, not only from Salisbury’s success, but from AAU travels. With the blessing of his local AAU coaches, Campbell and Jenkins had traveled with a Charlotte-based team and had played in front of big-time coaches at Rupp Arena in Lexington, Ky.

Campbell came up short of qualifying on his standardized test score, so he had two choices. There was a “Proposition 48” option that allowed athletes to sign with a Division I school, but they had to sit out a year. Then there was the junior college route. That was more appealing to Campbell. He didn’t want to sit out a year.

“I thought I’d lose a lot as a Prop 48,” Campbell said. “As a Prop 48, you were on the team, but at the same time, you really weren’t part of it. But then I looked at Midland College, looked at the competition I’d get to play against in Texas, and it was the better option. I never regretted that decision. Two years at Midland gave me a chance to get the books together. I did get homesick some, but I buckled down and I bonded with teammates. I got more recruiting interest at Midland than I ever got in high school. One day, the Midland coach told me he didn’t normally let freshmen talk to college coaches, but he was going to make an exception for me because (UNLV’s) Jerry Tarkanian was on the phone.”

At Midland, Campbell’s star rose, as a scoring machine and as the team’s top rebounder. He was all-region, all-conference and a Junior College All-American. He battled against players such as future NBA standout Larry Johnson, who was the star for Midland’s big rival, Odessa. Campbell had one of the best games of his life against Odessa.

In addition to Tarkanian, Jerry Green, the recruiter for Kansas coach Roy Williams, was hot on Campbell’s trail. Oklahoma coach Billy Tubbs wanted Campbell. N.C. State Jim Valvano dispatched assistant Dereck Whittenburg to entice Campbell to return to his home state. Georgetown, where Melvin Reid, who starred at Salisbury High and Pembroke State, had joined the staff, got involved. Georgetown’s interest was gratifying to Campbell. Growing up, he was a UNC fan when it came to the ACC, but he liked the rough, tough Hoyas even better. And then there was Barnes and Providence. Providence seemed like a longshot.

But two years in Texas convinced Campbell he wanted to get back to the East Coast for his last two years. He liked Whittenburg and N.C. State was at the top of his list until the summer of 1989 when Valvano stepped down, accepting blame for NCAA violations and academic neglect. Whittenburg advised Campbell to sit tight, that the chances were good that he would be named the next head coach. But then the Wolfpack opted to clean house, and Whittenburg was also gone.

Georgetown was attracting McDonald’s and Parade All-Americans in those days. Campbell opted for Providence, where the opportunity for playing time looked more promising.

He doesn’t regret that decision, either. He got to start games in venues such as the Carrier Dome and Madison Square Garden. He played on national television seven times in his junior season in 1990-91. He had the chance to play against Alonzo Mourning and against Ronny Thompson, the son of John Thompson, the Georgetown coach he grew up admiring.

“I was a small forward and my role was to defend some of the best college players in the country,” Campbell said. “I’d give the nod to the Big East, in those days, over the ACC or any other conference. The Big East was deep and physical. There were no touch fouls in the Big East. You had to take a beating to get a foul called. The most talented player I had to guard was Syracuse’s Billy Owens (the No. 3 pick in the 1991 draft). The hardest-working player was Malik Sealy (the 14th pick in the 1992 draft) at St. John’s. He never stopped moving. Sealy never took a play off, and their bigs never stopped setting picks for him.”

High-scoring guard Eric Murdock, Campbell’s roommate, had an amazing season for Providence in 1990-91 and became a first-round draft pick. Friars such as Campbell accepted their roles to help him. Providence’s 19 wins included monumental upsets.

Campbell had 11 points and six rebounds when Providence knocked off sixth-ranked Syracuse. He had 10 points and seven rebounds in a strong effort against UConn.

“Offensively, I was always the fourth or fifth option, so it was a complete role change from what I did in high school and junior college,” Campbell said. “But winning teams need defenders and rebounders, as well as scorers.”

Some of Campbell’s Providence teammates went on to pro success — Dickie Simpkins grabbed several championship rings as a member of Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls— but Campbell’s court days ended with college.

Off the court, he received a wonderful education, much of it from priests and nuns. There were long days with classes, three-hour practices and three-hour study halls, but it made him disciplined.

He’s thankful now for the Providence diploma on the wall. It still makes all the difference three decades after his graduation in May, 1992. He was the first in his family to get a college degree.

“I earned it, it’s mine and no one can ever take it away,” Campbell said. “Not everyone gets a chance at pro ball, but when you can put on your resume´ that you have a degree from a prestigious school like Providence, it opens doors. I’ve always had good jobs — Duke Power (now Duke Energy), Phillip Morris, R.J.Reynolds. I’ve been able to live a comfortable life.”

Campbell married Stephanie Wellington, a Salisbury girl, in 2001. They still live in Salisbury.

Campbell votes for Bobby Jackson as the greatest basketball player from Salisbury because “he made it to the highest level.”

Not many people would argue with that.

But in Rowan County, the next big thing is never far away. Some high school youngsters — Salisbury football’s Jalon Walker, West Rowan football’s Zeek Biggers and North Rowan basketball’s Brandon White — are getting a lot of attention.

“There are still a lot of good coaches here and there will always be great athletes coming out of Rowan County,” Campbell said.