Baseball obituary: Watson’s historic pro journey began in Salisbury

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, May 19, 2020

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — Salisbury had professional minor league baseball teams almost every year from 1925 to 1968.

The most successful MLB player any of those teams ever produced died on Thursday at 74.

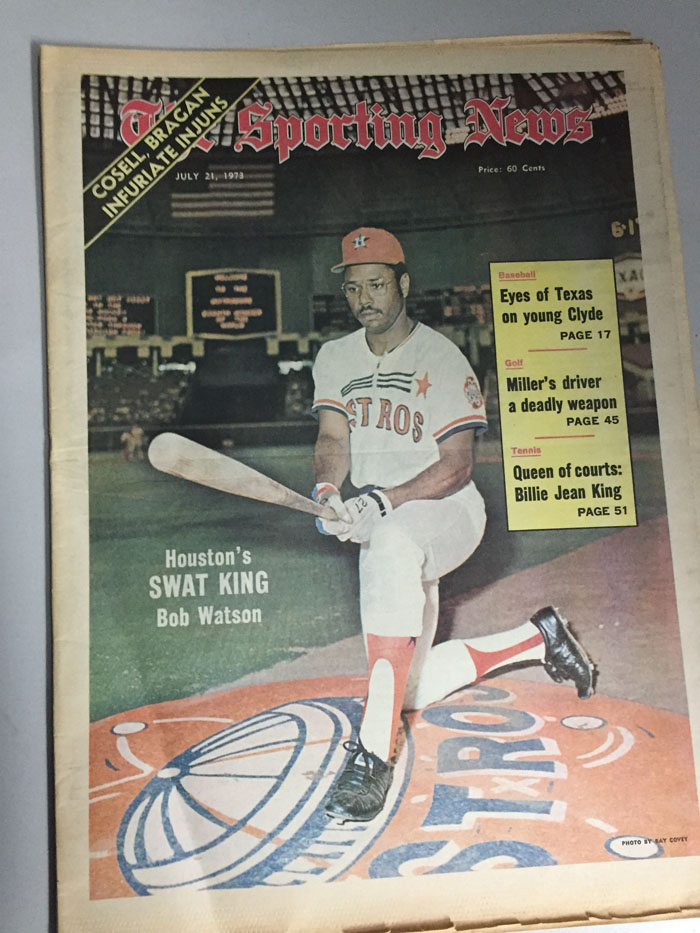

That was Bob Watson, who played for the 1965 Salisbury Astros at Newman Park, his first professional stop on a journey that would include a tremendous run in the big leagues. After his playing days, he made more history as the first black general manager of a World Series champion.

Watson spent six decades in baseball, compiling a unique and remarkable career.

In his days at Newman Park, in the Western Carolinas League, when he was a 19-year-old whose mighty bat was well ahead of his catcher’s mitt, he was usually referred to by the Post’s sportswriters as Robert “Bull” Watson.

“Bull,” because while he was not an extraordinarily large man (6-foot-1 and about 210 pounds in his prime), he was a man of legendary strength. He was one of those folks who could hurt people if he lost his temper, so he tried valiantly not to lose it. There was a day in Houston in 1975 when he didn’t have much choice. A fellow came at him at a stoplight, cursing at Watson, apparently upset that Watson was driving too nice a vehicle. Watson flattened him with a punch that caused blood to spurt from his eyes and ears. Watson broke his hand and missed the last three weeks of that season.

Born in 1946, a year before Jackie Robinson became a Brooklyn Dodger, Watson grew up in Los Angeles. He was raised by his grandparents. There was discrimination in L.A., but far more subtle than in the segregated South, where it slapped blacks right in the face. Schools were integrated in L.A. Watson’s 1963 high school team was the city champion and was a mind-blowing aggregation of talent that included five future major leaguers. Other than Watson, the most successful would prove to be outfielders Bobby Tolan and Willie Crawford.

The MLB draft would debut in 1965, but in 1963, everyone was a free agent as soon as they graduated from high school. The St. Louis Cardinals offered Tolan a ton of money. Crawford got a sweet deal from his hometown Dodgers. Watson, a catcher, wasn’t offered much of anything. Scouts advised him to go to college, so he enrolled at Harbor Junior College in L.A. He batted .370 at Harbor in 1964. Houston signed him in January, 1965, for the modest sum of $3,200.

Watson came north to Salisbury for the 1965 season with at least two more black players —Californian Curt Fontenot and Ed Moxey, who was from The Bahamas. Moxey was 22, had been a pro for four years and had already won two minor league batting titles, so there’s no rational reason why he was sent to Salisbury for another year of Class A ball.

Moxey had been through it all before, but Salisbury provided some serious culture shock for Watson. The black players weren’t allowed to stay in the hotel with their teammates. They stayed instead with a black family.

There was plenty of sports excitement leading up to the 1965 Salisbury Astros season. The Astrodome had opened, and Mickey Mantle socked the first homer there in an exhibition game. Jack Nicklaus won The Masters. Marvin Panch’s Ford won the Atlanta 500. Salisbury hosted the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association, as always, and writers from across the nation gushed about what a lovely place to visit Salisbury was.

The Salisbury Astros released a 124-game schedule for the 1965 season. Opening night tickets were $1, but they were reduced to 75 cents after that. A senior citizen could buy a season pass for home games for just $5. The Lexington Giants had 19-year-old Bobby Bonds. The Gastonia Pirates had sluggers Al Oliver and Bob Robertson. The Rock Hill Cardinals were managed by Sparky Anderson. The Shelby Rebels had 18-year-old Gene Tenace who would become a World Series MVP. The Greenville Mets had a wild lefty (Jerry Koosman), who had yet to master the curveball.

Opening night for Salisbury was April 21, with Lexington in town. Watson was catching and batting sixth in the lineup. His first professional at-bat came in the bottom of the second inning and he rocked a solo homer over the wall in left-center. He walloped a curveball. It was a blast that tied the game at 1-all. It was the only homer on a cold night. The homer was witnessed by 809 fans. Salisbury would win, 13-4.

Watson put together a fine season, usually in front of crowds of around 500, but his memories of Salisbury weren’t pleasant. When Salisbury Astros smacked home runs or got game-winning hits, they received coupons to be redeemed at a local restaurant for a Salisbury steak, which sounds like the perfect promotion. But only white players got steaks. Watson and Moxey, who got off to a fabulous start in 1965, were denied. They were refused service, even when they offered to take the steaks to go.

The black Astros weren’t welcomed in movie theaters, and they had an encounter on Main Street with men wearing hoods, sheets and robes. Watson had no knowledge of the Ku Klux Klan. Moxey explained who they were.

Houston drafted a catcher in 1965 and assigned him to Salisbury. Salisbury manager Chuck Churn asked Watson if he would try left field to make room for the new kid, Don Sessions, and Watson complied. He’d been catching a lot, and some rest was welcomed. He hadn’t been in the outfield long when there was a disaster in Greenville, where there was a brick wall in left field.

Watson hit that wall at nearly full speed chasing a long drive to left-center. He barely got his hands out in front of him before he hit. He broke his left wrist and the point of his right shoulder smashed into the wall, tearing ligaments. He would never throw well again.

Watson crumpled to the ground and briefly blacked out. When Watson came to, white center fielder Larry Bingham and Moxey were throwing punches almost on top of him. Moxey was unhappy that Bingham hadn’t said anything as Watson neared the wall. Blood was everywhere.

Watson’s season was over. In 80 games, he had 12 homers, 20 doubles, 55 RBIs and a 285 batting average.

That was the same summer Salisbury Astros pitcher Jay Dahl was killed and pitcher Gary Marshall was blinded in a car wreck that took the life of a female passenger. Yet, Salisbury won the regular-season pennant.

Watson played the 1966 season with his shoulder still a mess, but he batted. 302 in Cocoa Beach, Fla.

Watson got his first MLB at-bat late in the 1966 season against the L.A. Dodgers. He whacked a one-hop smash down the third-base line that John Kennedy backhanded and threw to first base for the putout. That would’ve been a double in Salisbury or Cocoa Beach, and Watson knew it. As he crossed first base, first baseman Ron Fairly told Watson, “Welcome to the big leagues.”

Watson’s minor league experiences in the South, as he fought his way to the majors, weren’t positive. In Florida, he had to sleep in a funeral home for several days, until a black family took him in.

He was close to giving up the baseball dream in 1969 when he started the season with the Houston Astros, but got off to a terrible start. After a game in Atlanta in which he sat the bench, he was sent down to Double-A Savannah, Ga. Watson found he couldn’t stay in any decent hotel in town in Savannah and slept on a training table at the stadium.

He left Georgia not long after that with the intent of retiring, but Tal Smith, then the Astros’ minor league director, met his flight, and told him Houston was bringing him back to the majors. This time, Watson stayed in the majors, but he needed one big break in 1970.

In 1970, Watson was probably the last man on the Astros’ roster — the fourth catcher, the third first baseman, the fifth outfielder.

But Joe Pepitone always had off-field troubles, and he had to travel to New York to settle a legal matter in court. Astros manager Harry Walker asked Watson if he still had a first baseman’s mitt, and Watson did. He was in the lineup that night in Atlanta against the Braves. He hit three homers in that series.

Watson had an unusual swing, a stiff-armed approach, short but sweet, the same swing Tommy Davis had used to pound the ball for the L.A. Dodgers in the early 1960s. Watson swung down on the ball, so he produced a lot more hard liners than towering homers. He didn’t strike out much. He hit the ball to all fields.

Some amazing things happened during the course of his career.

On May 4, 1975, he was credited with scoring the one millionth run in MLB history, although there’s plenty of dispute now about the math involved.

MLB hyped the moment big-time. There was a countdown, with official spotters in every ballpark. The player to score the milestone run would get a Seiko watch worth $1,000, one million pennies that would be given to charity, and one million Tootsie Rolls (almost all of which Watson donated to Girls Scouts and Boy Scouts.)

Two players were thrown out at the plate trying desperately to score that one millionth run. Watson was on second base when teammate Milt May hit a home run. Watson ran hard around third and finished a few seconds ahead of Dave Concepcion, who was sprinting around the bases on the home run he hit for Cincinnati.

Watson had a cameo role and a speaking part (one line) in the 1977 movie filmed in the Astrodome, “The Bad News Bears in Breaking Training.” He’s the Astro in the dugout that says “Hey, come on, let the kids play!”

Cycles in baseball (a single, double, triple and homer in the same game) are quite rare. Watson accomplished that feat twice, for the Astros in 1977, and for the Boston Red Sox in 1979. He was the first to do it in both leagues.

He played for the New York Yankees and Atlanta Braves late in his career and played in the 1981 World Series for the Yankees.

After retirement, he was a batting coach for the Oakland Athletics, and then the assistant general manager for the A’s.

At the end of the 1993 season, Watson was named general manager of the Astros. Officially, he was the first black GM to hold the title. Bill Lucas had all the duties of a GM, handling trades and contract negotiations for the Atlanta Braves in the 1970s, although his official title was vice president of player personnel.

Watson’s moves with Houston included trading aging pitcher Larry Andersen to the Red Sox for prospect Jeff Bagwell. That one turned out well for Houston.

As the GM for New York in 1996, Watson directed the Yankees to their first World Series title in 18 years.

Watson made the National League all-star team in 1973 and 1975. He was 11th in the MVP voting in 1976.

He totaled 184 homers and 989 RBIs in the big leagues and batted .295 for his career. He’s in the Astros Hall of Fame.

That long professional baseball journey started in Salisbury.

Plans for a future memorial service are pending. The family has designated the Boys and Girls Clubs of America as recipients of contributions.