Historian details attack on Hickam Field at Pearl Harbor

Published 12:01 am Thursday, January 30, 2020

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

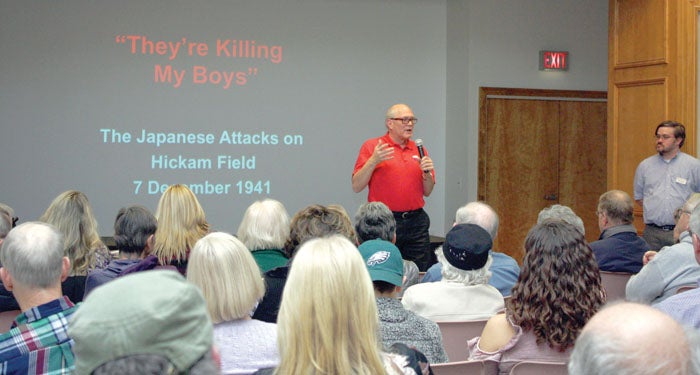

SALISBURY — J. Michael Wenger, a nationally known military historian, shared detailed knowledge Tuesday night of part of the attack on Pearl Harbor. His presentation was part of “Victory 45,” a yearlong celebration of the end of World War II.

Emotional at times, Wenger gave a detailed account of the Japanese attack on Hickam Field, where hundreds died and numerous aircraft were destroyed, delaying or prohibiting response to the attacks all over Oahu, Hawaii in 1941.

He showed many photographs of the attack, collected from veterans themselves, magazines, including some in Japan, and other sources, showing faces of both Japanese and American pilots and officers, bombed-out buildings, and the site as it is today.

Wenger has done extensive research including in Japan, where he learned the names of many squadron leaders and could see plans for the attack.

When researching there, Wenger said he respected the Japanese bravery and their love of their country, “but the misery they inflicted is immeasurable.”

“Nobody wants war,” Wenger said.

Oil was the central reason for the attack, Wenger said. The U.S. had cut supply lines to Japan and the country was quickly running out of fuel for the military, as well as oil for residents to heat their homes and cook.

Japan’s attack was intended to immobilize the Pacific fleet so Japan could get to much-needed oil in the East Indies. Wenger said Japan had already invaded many Asian countries, and expected them to line up to fight with them against America and its allies.

Both Japan and America knew war was coming, but the U.S. wasn’t sure where or when it would come to the Pacific.

So when the Pearl Harbor attack came, Wenger said, it was multi-faceted. The Japanese needed to disable the aircraft that could respond to an attack on the Navy’s fleet of aircraft carriers and battleships.

The attack was well planned, and took place after many of the personnel on the base had been off for weekend and spent it dancing, drinking, hanging out with their ladies. There was a general hangover in the quarters and barracks.

The attacks came so quickly, and from so many sides that the U.S., although well trained and prepared, didn’t see it coming the way it unfolded. We expected the attack in the Philippines.

When Japan hit, it used a huge number of aircraft, more than 400, with attack formations designed to inflict the most damage to the planes on the field, the bombers, the hangars and then the barracks.

With six Japanese aircraft carriers on the way, 183 aircraft struck at 6 a.m. in a planned pattern. Not all the runs were successful — one bomb intended for a fuel depot hit the restaurant, but one hangar was hit and completely destroyed, debris maiming many of the men on the field.

As sun rose over the base, the second wave moved in. Their targeting was not as successful, but it did hit another hangar.

The third wave was even less accurate, due to the smoke in the sky and other factors. Some of the angles of attack were wrong for the way the buildings were laid out on the field.

Wenger said the bombs did not hit the B-17 bombers out on the field but strafing of bullets began, along with cannon fire.

The men at Hickam were surprised and confused. Many began to panic, but Wenger told of one officer who warned his men they were there to serve.

As they tried to run from the explosions, more bombs hit.

Wenger said the barracks were bedlam.

At the base hospital, they quickly moved patients from the upper to lower floors, while a stream of casualties poured in, exhausting medical supplies.

After the first wave, Wenger described, an eerie silence fell as the people at Hickam Field collected casualties and tried to repair the planes. Families were being evacuated to Honolulu, knowing they might never see their husbands and fathers again.

When the second strike came, it targeted the Air Corps barracks, then the air depot. The metal framework of the hangars began to buckle from the heat of fires.

Clouds moved in, Wenger said, and that disrupted the bomb runs, forcing the Japanese aircraft to go below the cloud deck, where their targeting sites were not as effective.

Sixty-three bombs struck the barracks, killing men outright, many by concussion.

Wenger described the destruction as inexplicable, and said anger was raging throughout the personnel.

One commanding officer, wounded, but angry and determined to fight, cried out, “They’re killing my boys!” Wenger paused here, emotion overcoming him for a moment.

“We MUST remember their sacrifices,” he said. Knowing the history of the war and how so many died, “should represent a deep, visceral awareness as to what those men were called to do,” he said, ending his presentation.

Wenger is the author or co-author of at least 11 books of military history and is writing more. “I want to remember these men. I want you to remember these men.”

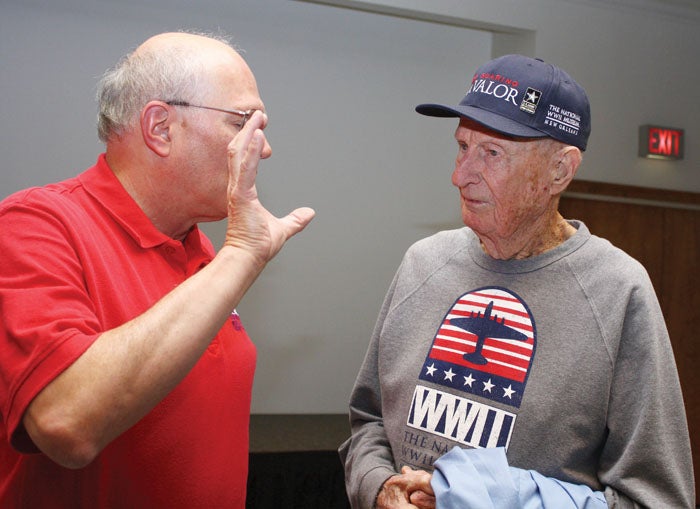

Several people attending the lecture were also well-versed in the history of the war, having had relatives serve and die there. They asked pointed questions about who should be blamed for what happened and who was disciplined at the time.

He pointed out that the early histories of the war were lacking something available to him — declassified files from the military. “There is so much more information available now,” he said.”We can do more intensive research.”

Wenger’s presentation is based on his book, “They’re Killing My Boys: The History of Hickam Field and the Attacks of 7 December 1941” (Pearl Harbor Tactical Studies Series).

The next event in the Victory 45 celebration will be “World War II Letters: The Gems they Hide” at 7 p.m. on Feb. 11 at the Messinger Room of the Rowan Museum 202 N. Main St.