‘Someone in their corner’: Foster parent shortage means some children without homes

Published 12:10 am Sunday, July 14, 2019

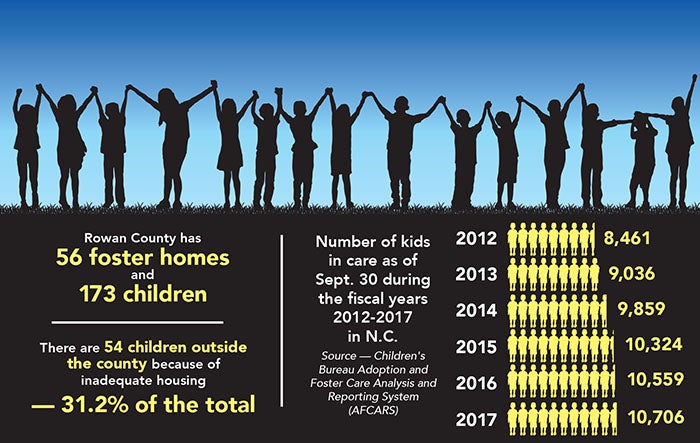

- Graphic by Andy Mooney, Salisbury Post

SALISBURY — At times, Rowan County social workers have slept overnight at the office to be with a foster child who’s sleeping on a cot because they couldn’t find a placement before the end of the day.

“It’s all done in as beautiful a way it could be done here,” said Micah Ennis, program manager at the Rowan County Department of Social Services.

The shortage of available homes in Rowan County and across North Carolina means there are times when a home cannot be found. By Ennis’ estimates, a foster child has slept on a cot or air mattress in the DSS offices three times over the past four years.

Currently, there are 173 foster children in the county but only 56 foster homes through both DSS and private agencies. And the number of foster children has been going up over time. An estimated 8,461 children were in foster care in North Carolina in 2012, according to the Children’s Bureau, a federal agency under the Department of Health and Human Services. In 2017, that number was 10,706.

“At the same time that we’re seeing a rise in the number of kids needing foster care placement statewide, we’re seeing a drop in the number of homes being licensed,” said Marc Murphy, foster care recruitment manager at Children’s Hope Alliance, a statewide child welfare agency.

The reasons for the shortage are numerous, but Murphy pointed to the opioid epidemic as contributing to the rising number of children who need homes. And the stigma associated with foster parenting, fear of the responsibility, and the recruitment practices of DSS and other agencies may play a role, too.

While some potential foster families may fear living in a fishbowl, others worry about being able to handle the task at hand effectively, Murphy said. But representatives of both the Children’s Hope Alliance and DSS said foster parents are not alone.

“It’s not a scary program,” said Nadean Quarterman, adoptions and foster home licensing supervisor at DSS. “We’re here to provide support. You’re never alone.”

A final factor in the shortage of homes might be confusion. Murphy said some people may not understand foster parenting.

“What we’re looking for is that commitment,” Ennis said. “A person that can say, ‘I’m not going to give up on you.’ Most kids just need someone to be in their corner.”

Part of the commitment is to the children’s families as well. Although the protocol used to be to keep foster children and their families separate, foster and biological families now work together when possible, Ennis said.

“We’re in the business of putting families back together,” Quarterman said.

• • •

Jennifer Nunn thinks one of the biggest misconceptions about foster parenting is that it’s synonymous with “parenting.”

She and her husband, Travis, have fostered close to 40 children since 2005. Their family also includes three biological children, two adopted children and four grandchildren.

“Parenting and fostering are two separate things,” Nunn said. “People think that you just get these kids and you can just love them and everything will be OK.”

For many foster children, their experience with trauma is what sets them apart, Ennis said.

“We need foster parents who help these kids gently unpack all of this trauma and then help them to repack it with a healthy outlook and a good sense of grit and support and hope. That’s really the job of a foster parent,” Murphy said. “To help a child feel safe, to survive these challenges and then to learn the skills to overcome them for whatever their next step is.”

Nunn’s own experience being raised by her aunt and grandmother inspired her and her husband to become foster parents. It informs the way they fulfill the role, too. Nunn says she is grateful that her aunt was transparent about her mother’s struggle with addiction and was willing to involve her mother in parenting when she was able.

“I always wanted to do that for somebody,” Nunn said.

Despite the number of children the Nunns have fostered, they maintain that the experience is unique each time.

To work with families, they have to understand and respond to each child’s specific background and needs. Sometimes this requires doing things they might not have done with their own children.

The Nunn household doesn’t celebrate many holidays, but that wasn’t true in winters when they fostered children who had grown up celebrating Christmas.

“That year, we had to do Christmas big,” Nunn said. “We had to keep that just to let them know that you’re important and you have a say-so as well. Sometimes it can be hard.”

Consideration of the needs of individual foster children also comes into play when they are placed with families.

When DSS or private agencies place foster children, case workers have to consider how they can put them with a family that can best provide a feeling of safety as well as attend to their physical needs. Factors such as race, sexuality and mental health can all sometimes play a role in what a child needs in a foster family to feel safe, Murphy said.

Ideally, Social Services and other foster care agencies would have as diverse a group of foster parents as the children needing care. If children are coming from trauma, it might be an easier transition if they are placed with a family who looks like them, Murphy said. That’s despite the fact that all foster parents like the Nunns are trained to care for children different than themselves.

“It is really our obligation to seek out families that reflect our children in care,” Ennis said.

The shortage of foster homes in Rowan and surrounding counties, though, has made that difficult at times.

Particularly, Rowan County Social Services is in need of African-American and Latino homes in addition to families who are willing to take teenagers or LGBTQ youths.

Children’s Hope Alliance has many foster parents looking to foster newborns but needs homes for children with emotional or behavioral needs; sibling groups; children ages 6-17; children who have experienced trauma, abuse or neglect; and children who identify as LGBTQ, Murphy said.

Whether or not there are families of all categories available, federal legislation prohibits the delay of a foster child placement if there isn’t a family that matches their ethnicity or race.

• • •

One potential effect of the shortage of homes and the lack of diversity in foster homes is that children can be put in less-than-ideal placements, such as a teenager being placed in a group home when he might benefit from a home setting, Murphy said.

The shortage also can lead to overcrowding in existing foster homes, Murphy said, and that can bring foster-parent burnout and a higher likelihood that a child would be unexpectedly moved from a foster home. It also means that siblings are separated.

If there isn’t an appropriate home in the county, DSS sends foster children to homes in other counties, potentially putting significant distances between the children and their social network, case workers, school, and medical or mental health professionals. Fifty-two of the children in foster care in Rowan County don’t actually live in Rowan County because there is no foster home available to meet their needs. That is 31.2% of the total number of kids in foster care in the county.

For foster children, being removed from their surroundings on top of being removed from their birth parents sends the message that “everything I love or get attached to, I have to leave,” Jennifer Nunn said.

The Nunns said they feel the shortage of foster families personally. They prefer to stay involved in the lives of their foster children after they move on, likening their position to either aunt and uncle or grandma and grandpa. Travis Nunn walked one former foster child down the aisle at her wedding.

When children are placed outside the county, foster parents can’t fill this role as easily, or sometimes at all.

The Nunns fostered one boy for two years before he had to be transferred. Jennifer Nunn said she wants to stay in contact with him, but he now lives four hours away. She and her husband can’t make that a trip in a day, especially when they are still fostering.

She says they and the child both cry when they talk on the phone.

“If we had more families, I would be there to support him,” she said. “I want to see him. I want to give him a hug.”

• • •

DSS has changed some of its recruitment practices because of the foster parent shortage and the shortage of certain types of homes. They hope that targeted recruiting helps, but also that people take note and refer families to the system.

“We would like to make it a community responsibility to get families in and take care of our children,” Quarterman said.

In the meantime, the shortage affects all foster children.

“When the kids don’t get the chance to do deal with their trauma and they get older, they repeat cycles of abuse, they repeat addiction, they repeat domestic violent relationships, they end up in the ER, they end up sick, they end up harming themselves and others,” Murphy said. “We are either going to have to deal with it on this end or we’re going to deal with it on the back end.”

Anyone interested in being a foster parent or otherwise helping should contact the Rowan Department of Social Services at 704-216-8440 or Children’s Hope Alliance at 844-791-3117 or childrenshopealliance.org.

Natalie Alms is a news intern at the Salisbury Post. Contact her at 704-797-4277.