Training helps teachers build relationships with students who experienced trauma

Published 12:00 am Saturday, April 27, 2019

By Maggie Blackwell

For the Salisbury Post

SALISBURY — Thomas Lowe’s fifth-grade class at Koontz Elementary School is studying fairy tales.

He’s asking rapid-fire questions, and the students are anxious to answer. It’s clear they want to please him.

“Give me an example of a modern Disney fairy tale,” Lowe says.

The students suggest Shrek, and Lowe agrees that the story is, in fact, a fairy tale.

He continues to ask questions: What was the problem in Shrek? Is this fiction or nonfiction? The students wave their hands eagerly.

Lowe’s responses are key: “See, you know a lot about that.” “See, you were paying attention.” “Thoughtful answer; raise your hand next time.”

Phyllis Post’s graduate assistants nod and smile when Lowe delivers this kind of feedback to the children. He’s following training they gave Koontz teachers earlier in the year.

His responses don’t judge; he doesn’t say, “Good answer” or “Bad answer.” Instead, he encourages every student with his responses.

Post, a doctoral professor in counseling at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and Christy Lockhart, of the North Carolina Resilience and Learning Project, have worked together to teach teachers how to work with children who experience trauma in their lives. It’s called Child-Teacher Relationship Training.

One of Post’s favorite quotes is by Urie Bronfenbrenner: “To develop normally, a child requires a relationship with at least one adult who has an irrational emotional relationship with the child. Somebody’s got to be crazy about that kid. That’s No. 1. First, last and always.”

So she has trained Koontz teachers to be that person.

“Our program is with the teachers, not the children,” Post says. “My idea in initiating this project is this: for children in this world, the most important factor is a significant relationship with an adult. You have 500 children in a school with 96% qualifying for reduced lunches; 100% of those children qualify for food stamps. (That) leaves 20 kids in the whole school who are not on food stamps.

“We don’t have control of what goes on at home, but we can control what happens here.”

One of Post’s graduate assistants, Claire Cronin, recalls a conversation she observed between two students.

“They’re second-graders,” Cronin says. “The radio had said with the government shutdown, this may be your last food stamp payout for a while. One of the girls said, ‘My mom said she might not get paid for food for a while.’

“You could see on her face there was a lot of anxiety. The teachers report the kids internalizing and externalizing lots of issues.”

Another assistant, Amy Graybush, says children deal with a lot of stress.

“There are ‘big T’ traumas, and there are also toxic stressors,” Graybush says. “They all kick in our fight-or-flight syndrome and can cause behavior and health issues for children.”

Post and her assistants spent 12 weeks training teachers and practicing on each other. Then they visited classrooms, coaching teachers and modeling skills for them. Starting with a program developed by Garry Landreth, Post’s mentor, she infused material about social justice, trauma and racial issues. She and her graduate students trained 24 teachers at Koontz.

Post says they gave the teachers basic skills that are important to develop. One of the skills is called “return responsibility.” Graduate assistant Aziz Elmadani says it gives the students a voice and allows them to make choices. After making positive choices, the students develop confidence and independence.

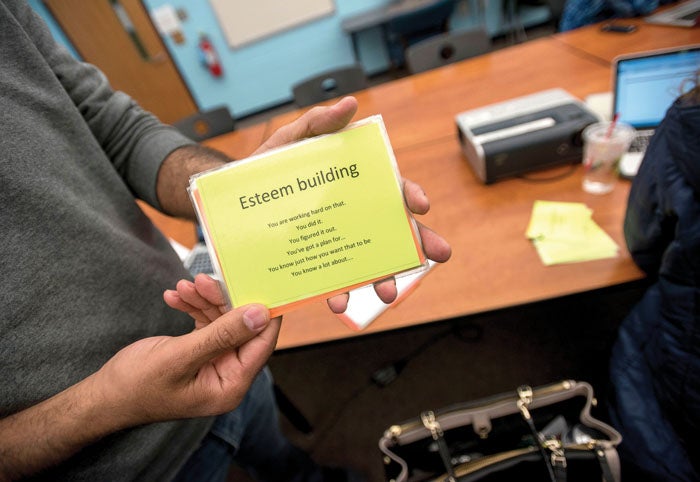

Another skill is “esteem building.” Teachers observe, “You’re working hard on that” or “You really know how to plan.”

This is what Lowe demonstrated with the fairy tales. Post says it takes away judgment and gives the child self-esteem. Teachers implement this, Post says, and they see accomplishment on the children’s faces.

Paraphrasing is another tool. The teacher repeats what the child said, using different words. It tells the child he was heard and he matters.

There are other tools as well.

“What we’re trying to help the children hear is, ‘You matter,’ ‘I’m here,’ ‘I hear you,’ ‘I understand you,’ and ‘I care about you,’” Post says.

Post’s initial intention was to train the teachers at Koontz and then next year, teach them how to train their colleagues. The future of the school, however, is uncertain, and it has affected Post’s plans.

The Rowan-Salisbury Board of Education has considered several options for the future of Koontz. One is to transfer all the students and use the building for a trade school. Another involves transferring some Koontz students, closing Faith Elementary and merging Faith into the Koontz building.

Teacher assignments at Koontz are unsure for next year.

For this day, the training is complete, and the teachers are integrating the principles into everyday interactions with students.

Post shares a story about a fourth-grade teacher who had a student acting up one day. He was being aggressive, and the teacher remembered her training under Post. She took the student into the hall and said, “I think you are feeling sad today.” The child was silent for moments, then said his home was broken into the night before.

The teacher listened. Finally, she said, “That must have been scary.”

They took a few minutes to process the situation and returned to the classroom. The student was calm and engaged the remainder of the day.

Post interviewed another teacher who said, “I used to think when kids misbehave, they need juvenile help. Now I realize they have something going on.”

Post approached the project like the scientist she is. She surveyed all the teachers before the training to identify their positions on myriad things. She surveyed North Rowan Elementary School teachers, as well, as a control group.

Post can’t say enough about the support both principals, Lori Morrero at Koontz and Katherine Bryant at North Rowan, gave her for the project.

Post tentatively plans to return to Koontz next year, depending on the support of whoever the principal may be. Her work was funded by local philanthropists Fred Stanback and Greg Alcorn and an undisclosed donor. She’s seeking more financial support for next year.

Graduate assistant Elmadani says the program has helped him grow.

“It’s important to advocate for teachers and students and develop relationships,” he says. “I want to take these skills home to Morocco. It has been a great experience. It helps me as someone who came from a different culture. Now we can shift the knowledge to another country.”