Holocaust survivor’s daughter shares story of ‘brightest light’

Published 8:29 pm Monday, March 18, 2019

- Tammy Grinshpon, the daughter of Holocaust survivor Ela Weissberger, shared her mother’s story to a capacity crowd Sunday at Temple Israel. Maggie Blackwell/for the Salisbury Post

By Maggie Blackwell

For the Salisbury Post

SALISBURY — “‘It’s up to you to ensure the story never goes away,’ she told me. ‘This story can change the world, make the impossible possible.’”

Tammy Grinshpon, the daughter of Holocaust survivor Ela Weissberger, shared her mother’s story to a capacity crowd Sunday at Temple Israel.

Weissberger passed away just a year ago but spent the last years of her life sharing the story of life in Theresienstadt, the “model community” concentration camp. One of Weissberger’s eulogies remembers her as the “brightest light in the darkest night of our history.”

Weissberger’s father was a successful businessman and philanthropist in their Czech town, Grinshpon said. When rumors floated about a campaign against Jews, he was in denial that such a thing could happen. In 1938, when her mother was just 8 years old, the Germans came at Kristallnacht, and the family never saw Weissberger’s father again.

Weissberger’s mother and grandmother were told they had 24 hours to board up their home, gather their belongings and report to the border.

This was their journey to Theresienstadt, Grinshpon said. She explained that Theresienstadt, originally a garrisoned city, was used by the Germans as a holding place for Jews.

About 140,000 Jews passed through the compound. From there, they were sent to Dachau to be killed. Although no one was gassed at Theresienstadt, more than 30,000 died there as a result of the conditions or disease.

As the world began to suspect that Germans were killing Jews, the Germans set up Theresienstadt as a model town. They painted the buildings and planted flowers.

Hans Krasa, an interred Jewish musician, had covertly written the children’s opera “Brundibar,” about a mustachioed villain who is overcome by children and creatures of the forest. Tella Pollak, a music teacher, had been teaching it to the children in the camp.

Weissberger was chosen to play the role of the cat. Grinshpon said her mother wore her mother’s black ski pants and her sister’s black sweater as a costume. An adult painted whiskers on her face with a little shoe polish.

The children treasured the opportunity to sing, Grinshpon said, because it was the only time they did not have to wear the yellow star marking them as Jews.

“It was a moment of freedom,” she said.

In June 1944, the Red Cross sent an envoy to Theresienstadt to investigator whether the rumors were true that the Germans were killing Jews. Instead, they found the “model town” with colorful buildings and gardens.

The Red Cross representatives saw the first performance of “Brundibar.” They were convinced.

Grinshpon shared a clip from the TV show “60 Minutes” in which Weissberger said, “They convinced the world because it wanted to be convinced.”

Altogether, the children performed the opera 55 times. As boys aged out and went to be gassed, they were replaced by younger boys.

Music gave the children hope to go on, Grinshpon said, and was key to Weissberger’s survival. Friedle Dicker Brandeis, an adult in the compound, secretly taught the children art lessons and encouraged them to hide away their creations.

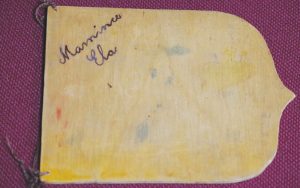

Weissberger found a scrap of wood and asked a man to cut it into the shape of a shield. She decorated it on the front to resemble a coat of arms. On the back, she burned into the wood the words “Mamince” (Mama in Czech) and “Ela.” She gave it to her mother for her birthday at Theresienstadt.

Later, her mother said it was the best gift she ever received.

Grinshpon shared the plaque for the audience to see.

Weissberger was liberated from Theresienstadt in 1945 and later emigrated to Israel, then to the United States. Her mother and sister survived, as well. She lived in New York and developed a thriving interior design business, with many well-known names among her clientele.

Grinshpon attended the New York School of Design and joined her mother in the business.

“People asked me all the time, ‘How can you work with your mother?’” Grinshpon smiled. “I told them it’s easy to work with someone you love so much.”

Grinshpon closed her presentation with a poem her mother taught her. The children of Theresienstadt would chant the poem to each other. The poem was originally in Czech, but Weissberger translated it into English.

“You and I

We are friends

And you and I

We love each other.

In Therezin we met,

Friends in need,

Hand in hand,

And you and I friends will still be.

And you and I shall never forget.”

Grinshpon’s appearance in Salisbury was sponsored by the 49 Days of Gratitude Project.