The mystery of Peter Stewart Ney endures 250 years after his birth

Published 12:00 am Sunday, January 6, 2019

By Gary Freeze

For the Salisbury Post

Folks often tell me I have it easy teaching history. “It’s happened,” said one Salisburyian to me years ago. “So what have you got to do that’s new?”

Nothing could be further from the reality of my life as a regional historian the past two decades. From the discovery that Ulster emigrants to Poplar Tent used thatch for roofing to the maps that show how China Grove was considered to be the originating point for the railroad to Asheville, to the blinders that folks on both sides put over their eyes about Confederate monuments, history is more plastic than wooden, more fluid than solid, and always (always!) a mystery.

There still resides in west Rowan a mystery to be contemplated, and 2019 is a milestone year for its recurrence in our consciousness.

On Jan. 10, 1769, was born Michel Ney in the Alsatian borderlands between France and Germany. The sestercentennial (that one is for you, Patsy Reynolds) of his birth serves as a platform to consider whether this great Napoleonic general actually ended up being executed in 1815 after the battle of Waterloo — as the textbooks maintain — or perhaps lived in exile for decades in this part of North Carolina, dying in 1846 as a celebrated schoolmaster who called himself Peter Stewart Ney.

Rowan residents have been trying to figure out who was who ever since, to no resolution.

Even today, we know a lot more about Michel Ney than we understand about Peter S. Ney. The former, the son of a blacksmith, not wealthy, marginally educated, became an early convert to the fervor that almost took Europe: Bonapartism. Ney joined the French army after the Revolution and within a decade rose from the ranks to be one of its heroes.

As a field marshal, he fought with elan in battle after battle, exhibiting a “rage militaire” so empowering it had a percussion-like effect on nearby soldiers. Napoleon himself called Ney “bravest of the brave.” Shot by a firing squad for being a traitor for helping Napoleon, Marshal Ney was buried in Paris.

The man who styled himself Peter S. Ney affected a Scottish accent, showed an astonishing breadth of erudition, and moved about frequently from school to school in the watershed of the Yadkin and Catawba rivers. He may have been the most effective teacher of young people in 19th-century North Carolina.

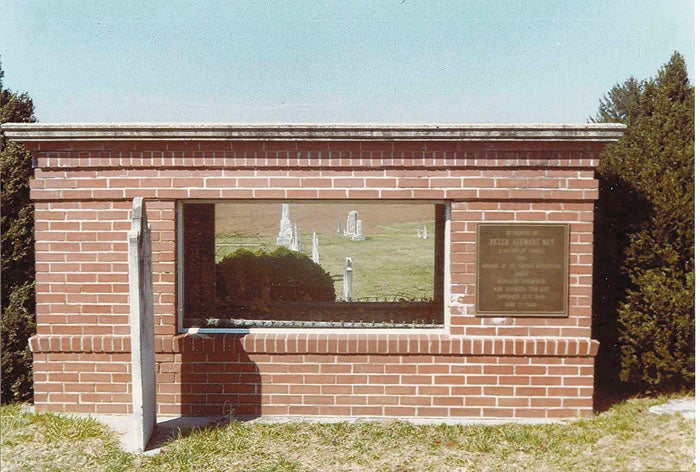

In an almost biblical manner, descendants of his students have venerated his memory to the current generation. In the manner of Chaucerian pilgrims, they’ve written homilies to him, dug his body up to view it, and placed over his grave at Third Creek Presbyterian Church a mausoleum that would do credit to Sufi saints.

And they’ve tried to figure out if he told the truth on his deathbed: “I am Ney of France!”

Was he? Well, that remains one of history’s mysteries.

Why? Because almost every piece of evidence that provides the clincher can be contradicted. For example, Peter S. Ney kept secrets but would tell his students he was the famous Frenchman in very specific and copious detail. He seemingly was hiding in exile yet wrote letters back to France that were delivered in diplomatic dispatch bags, clearly letting anyone know his whereabouts.

He was an itinerant country schoolmaster yet had a line of credit — source of funds unknown — with the Bank of the United States in Washington, D.C.

Perhaps the most intriguing contradiction is the story of his third son, Eugene, a French aristocrat who lived well into the 19th century. He came to America and said forcefully he had seen his father’s body when it had been reinterred in Paris. Yet there was another version of that son, an Indianan named E.M.C. Neyman, who became a national celebrity by trying to claim P.S. Ney’s body and take it to a cave near his home. (Third Creek elders said no.)

I have experienced the lingering effects of Ney in many places. In 1996, Kevin Cherry — today’s director of state archives and history — sponsored a program at the Rowan Public Library that featured me bloviating, then a play, “Ney, Nay. Double Ney!” written by Catawba theater professor Jim Epperson and read by theatrist James Parker.

More than 100 people crowded into the room.

More than 50 came to a program Gretchen Witt, director of the library’s local history room, and I did in Iredell County’s tiny town of Harmony, where P.S. Ney taught for years. I have had a chance conversation with a Masonic historian about Ney in the shadow of Alexandria, Virginia’s Washington Monument, generated by me telling him where I was from.

Most amazingly, I had a similar encounter in Cairo, Egypt, with a historian who wrote about Parisian mystics from the mid-1800s, including “Ney’s son.” (He had no sympathy for the idea that Ney would end up in the Carolina backwoods.)

I have been on a cable network “mystery” show to discuss it. Yet I do not know the answer.

So this year, let’s celebrate the joy of the uncertainty. In addition to putting flowers at the tomb Thursday, I plan to have a Catawba Community Forum to explore the mystery of Marshal Ney sometime this spring.

There will also a program to celebrate P.S. Ney as a Rowan schoolmaster when the new West Rowan library branch is opened this year. The plan is to pay tribute to this story there as part of our local heritage.

I am also looking for a copy of a short film that was produced in the late 1930s on the subject and will work with my Catawba College students to do a bloggable website about all this stuff.

Who knows, maybe there’s the possibility of an app?

Gary R. Freeze is the William R. Weaver Professor of Humanities at Catawba College.